Three mothers

The 'Mothers' is a term from the ancient Mysteries, that appears in Plutarch (ca 46-119 AD) and Goethe's Faust. There are also three Mother letters in ancient Hebrew.

The plural Mothers is an expansion of the term we know on Earth today as the mother of a child or mother Nature, both referring to the physical material.

Mothers refers to the forces, and the corresponding planes or worlds of consciousness from which the creative forces are generated, that underlie the four kingdoms of nature. These forces have a relationship to their development during the previous planetary stages, but they still work in nature on Earth today. Hence we have three mothers of the different kingdoms and worlds.

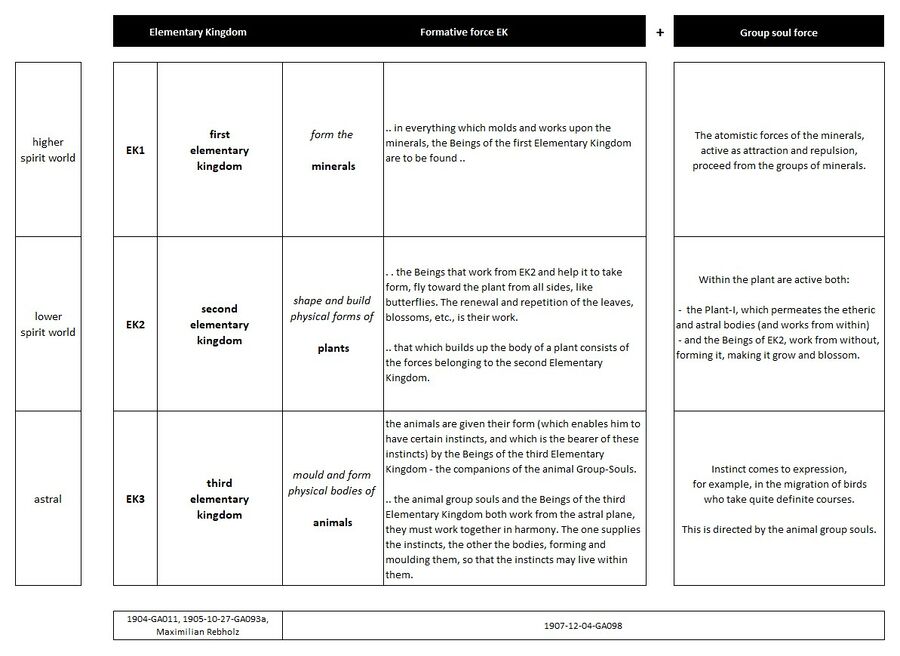

In each of the three worlds besides the physical (astral world and lower spirit and higher spirit world), can be distinguished: a) the formative forces of The elementary kingdoms, and b) the consciousness of the group soul of a corresponding kingdom of nature (animals in astral world, plants in lower spirit, and minerals in higher spirit world). See Schema FMC00.175A.

In practice, the world around us is thus the result crafted by interpenetrating forces that are all working together at the same time, and these are the Mothers of creation.

In Greek culture Rhea, Demeter and Persephone were three world-mothers. Rhea was mother of Demeter, Demeter mother of Persephone. As such one can relate them to Old Saturn, Old Sun, and Old Moon, as every next planetary stage is given birth as the result of the previous one. Each of these stages of evolution brought the development of new higher ethers and lower elements from the corresponding strata in the higher worlds.

In literature references, the term Mothers is a broad concept and hence once one knows what it means, one should not get confused that it can be used to reference one of the aspects above, such as the layers of the spirit world, or the formative forces.

Aspects

- The Greek also saw in these Mothers "those forces that, working down out of the cosmos, prepare the human cell in the womb"

- the three soul Mothers

- the three figured Egyptian Isis: images representing not one Mother but three Mothers, representing the three natures of the human soul: a will, feeling and wisdom nature.

- In front the physical, human Isis with the Horus child at her breast

- behind this another figure, more spiritualized: an Isis, bearing on her head the two familiar cow horns and the wings of the hawk, offering the 'crux ansata' to the child

- Behind yet a third figure, bearing a lion's head and representing the third stage of the human soul.

- see also the three daughters of Persephone: Luna, Astrid and Philia; see also: Greek mythology#Persephone, Demeter, Rhea, Eros, Hecate, Luna, Astrid, Philia

- the three figured Egyptian Isis: images representing not one Mother but three Mothers, representing the three natures of the human soul: a will, feeling and wisdom nature.

- regarding the word 'Mother' and the (three) Mother letters in Hebrew

- Rawn Clark (in the Book of Taurus (2024),p 39) maps the three horizontal paths of the Gra Tree of Life to the hebrew mother letters as follows: shin/fire to the path in the higher spirit world, aleph/air to the lower spirit world below, and mem/water to the astral world. Compare how this maps to the warmth, light and chemical ethers, eg on Schema FMC00.149 (and more info Spectrum of elements and ethers) and corresponding Old Saturn (two types of warmth, Old Sun (light/air) and Old Moon (chemical/water).

- various:

- morning dawn (morgenrot), with reference to Jacob Böhme’s Aurora, is the symbol or key that leads to the Mothers Old Saturn, Old Sun, and Old Moon (from GA265A)

Illustrations

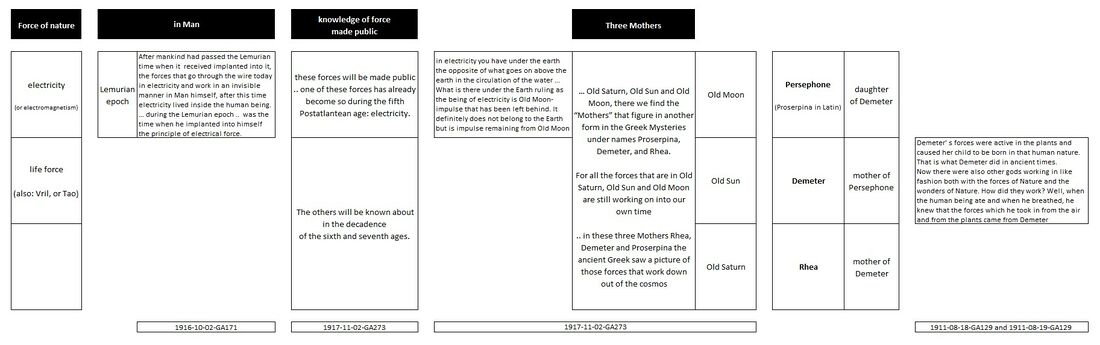

Schema FMC00.030 shows the three main forces of nature, related to the formative etheric forces corresponding to the three previous planetary stages of evolution, and still working through on Earth.

Compare with Schema FMC00.142A: light in the sub-material state is electricity and corresponds to the astral and EK3. The other two forces map to the lower and higher spirit world and EK2 and EK1. The second force, known by the Atlanteans as Tao, and now more popularly known as Vril, is indeed the growth force of nature.

Schema FMC00.175A is a simplified variant of Schema FMC00.175 that summarizes the formative forces proceeding from the Elementary Kingdoms, all three active and interpenetrating all the time. They work together with the intelligence of the group soul from the different worlds.

Lecture coverage and references

Plutarch

the story of Nikias, who wanted to make subject again to the Romans a certain town in Sicily belonging to the Carthaginians, and on that account was being pursued. In his flight he feigned insanity, and by his strange cry: “The Mothers, the Mothers are pursuing me!” it was recognized that this insanity was of no ordinary kind. For in that region there existed a so-called “Temple of the Mothers,” set up in connection with ancient Mysteries; hence it was known what was signified by the expression “the Mothers.”

Goethe

- second part of 'Faust'; the moment Mephistopheles mentions the word ‘Mothers’ Faust shudders, saying what is so full of meaning: “Mothers, Mothers! How strange that sounds!” And this is all introduced by Mephistopheles' words “It is with reluctance that I disclose the higher mystery

- the ‘Realm of the Mothers’ in connection with Helena

- three Mothers seated on golden tripods

1901-11-30-GA087

The best-known Greek myth is that of Demeter and her daughter Persephone and then the myth of Dionysus, which has already been mentioned several times. Demeter, one of the supreme female Greek deities, was first understood in a naturalistic sense. She had a daughter with Zeus, Persephone. She was stolen by Hades, the god of the underworld. Hades had asked to be allowed to take this daughter as his wife in the underworld. She was only to remain in the upper world temporarily. She was to remain two thirds in the upper world and one third in the underworld. This myth, which is alive everywhere in Greece in its naturalistic meaning, was also that which was to be found in certain mysteries, namely that on which the Eleusinian Mysteries were based. This myth also had a threefold meaning. The naturalistic meaning lies simply in the fact that one understands the actual as such, that one has a mythological history of the gods. The second conception would then be something that took place in [Greek] life, and that was the marriage of the Ionian spirit with the Doric.

The Greek people were divided into tribes. Among the most important were the Dorians and the Ionians. The myth of Demeter had originated among the Dorians, and the Ionians had adopted it and mixed it with the myth of Dionysus. We are interested in the Dionysus myth because it leads to an esoteric view. Dionysus is also a son of Zeus and Demeter. He was torn to pieces and only managed to save his heart. From this, Zeus had formed the younger Dionysus. But he could no longer take the limbs. It is therefore the case that the world represents the scattered limbs. This therefore represents the marriage of the Dorian Persephone with the Ionian Dionysus. The fusion of these two views has thus taken place in this myth.

But what remains to be noted is the third, the divine conception. We can only understand this historically if we stick to the sparse information we have. We are first referred to the temple in which the service of Demeter takes place. This Demeter service is a service in which we encounter the three deities mentioned. Demeter herself is one of the greatest deities of Greece, symbolically shaped, with the inscription: "I am the origin of the soul, I am the origin of the spirit." At her side, Persephone is presented to us with the inscription: "I am death and carry within me the secret of life." Her brother Dionysus is presented to us with an even stranger inscription: "I am death, I am life, I am rebirth and adorned with wings." - If we understand this, we come to the interpretation of one of the most important Greek myths. Demeter loses her daughter. She has to give her Persephone to Hades. She could return to her mother if she had not already partaken of the fruit of the pomegranate with Hades and was therefore unable to return completely. This Persephone is supposed to save her brother. Only this makes it possible - now in a deeper sense - for Persephone to return, for Dionysus to sacrifice himself. We have to look at these two in context again. We must recognize that sacrifice is what matters here. This is shown to us by the fact that Orpheus - who is originally credited with having communicated the deeper content of this to the Greek people - was also sacrificed, for he is also said to have been torn apart and to have lived on as a spirit by having flowed out into the world matter. The child of eternal life must be sacrificed to Hades, to Pluto. We can only understand this if we see the material world in Pluto. Thus, according to the esoteric view, we see in Demeter the universal spirituality, the primordial mother of intelligence, and in Hades the material world. In the whole Persephone myth we see the necessity of Persephone's falling away from her mother. The daughter must enter matter. She must partake of the pomegranate of the underworld. Now she can no longer save herself from matter and therefore a second sacrifice is necessary. Persephone's brother, Dionysus, must sacrifice himself again. He must allow his [own] spiritual nature to flow out into the gross nature, so that Persephone now enters into a spiritual marriage with her brother, but can flow back again to the original spirit of the primordial mother, Demeter. This mystery of the spirituality's necessary departure from itself, this immersion of the spirits in the material and this longing of the spirit to return to the spiritual is expressed in the Demeter myth.

1904-01-28-GA088

The next higher sphere hosts the beings called dynamis. They have not only the power of thought but also the power to be a source of thought; they are beings that have the seeds for thoughts. Compare the exusiai with flowers. Now imagine a seed that is transparent, bright, and clear, but also has the power to become a flower. Thus through these beings a seed of thought can be formed; and then from the other side, the entire thought can be built into the akasha; that is the sound, so to speak, of the entire fabric of the world.

As Goethe described this in Faust, this is where forms are created, where the mothers sit on their thrones in loneliness and work at their glowing tripod.

As I already said, in Plutarch's time this kingdom was also called the kingdom of the mothers. If you read about the kingdom of the mothers in Plutarch, this story will reveal an entirely new meaning.

The beings we call kyriotetes sound forth in the highest kingdom. Only the most highly developed human beings can gain even a brief glimpse into this kingdom. Everything is harmony and unity there; all exception has disappeared.

The exusiai, the dynamis, the kyriotetes are the three highest kingdoms in which human abilities are completely free. These are the kingdoms we enter in the time between two incarnations in order to find forces from what lies on the other side, for work we must do on this side of world existence. What happens on this side of existence, what we do ourselves, this is the world of results, the world of action. New forces for existence flow to us from the world of causes when we return to a new incarnation. Everything that we do in this world, that rises into our soul as moral ideals, as ability to work creatively, as daily love for fellow human beings, everything that occurs to us for mastering the forces of nature in technology, all this resides hidden deeply in the human soul. The soul brought it from the kingdom of higher devachan, where the initiatives for work on this side of the threshold are found.

1906-06-08-GA094

is just a short reference in the context of describing the akashic records (re Clairvoyant research of akashic records#1906-06-08-GA094)

At the fourth stage of Devachan, the archetypes of things arise — not the ‘negatives’ but the original types. This is the laboratory of the Cosmos wherein all forms are contained, whence creation has proceeded; it is the home of the Ideas of Plato, the ‘Realm of the Mothers’ of which Goethe speaks in Faust in connection with Helena. In this realm of the spirit world, the Akashic Record of Indian philosophy is revealed. In our modern terminology we speak of this Record as the astral impression of all the events of the world. Everything that passes through the astral bodies of men is ‘fixed’ in the infinitely subtle substance of this Record as in a sensitive plate.

1909-04-29-GA057

1911-08-18-GA129

1911-08-19-GA129

1914-GA018 Part 1 - Ch 2.

see also

In the view of Pherekydes the world is constituted through the cooperation of these three principles. Through the combination of their action the material world of sense perception — fire, air, water and earth — come into being on the one hand, and on the other, a certain number of invisible supersensible spirit beings who animate the four material worlds. Zeus, Chronos and Chthon could be referred to as “spirit, soul and matter,” but their significance is only approximated by these terms. It is only through the fusion of these three original beings that the more material realms of the world of fire, air, water and earth, and the more soul-like and spirit-like (supersensible) beings come into existence.

Using expressions of later world conceptions, one can call

- Zeus, space-ether;

- Chronos, time-creator;

- Chthon, matter-producer

.. the three “mothers of the world's origin.” We can still catch a glimpse of them in Goethe's Faust, in the scene of the second part where Faust sets out on his journey to the “mothers.”

As these three primordial entities appear in Pherekydes, they remind us of conceptions of predecessors of this personality, the so-called Orphics. They represent a mode of conception that still lives completely in the old form of picture consciousness. In them we also find three original beings: Zeus, Chronos and Chaos.

Compared to these “primeval mothers,” those of Pherekydes are somewhat less picture-like. This is so because Pherekydes attempts to seize, through the exertion of thought, what his Orphic predecessors still held completely as image-experience. For this reason we can say that he appears as a personality in whom the “birth of thought life” takes place. This is expressed not so much in the more thought-like conception of the Orphic ideas of Pherekydes, as in a certain dominating mood of his soul, which we later find again in several of his philosophizing successors in Greece. For Pherekydes feels that he is forced to see the origin of things in the “good” (Arizon). He could not combine this concept with the “world of mythological deities” of ancient times. The beings of this world had soul qualities that were not in agreement with this concept. Into his three “original causes” Pherekydes could only think the concept of the “good,” the perfect.

Connected with this circumstance is the fact that the birth of thought life brought with it a shattering of the foundations of the inner feelings of the soul. This inner experience should not be overlooked in a consideration of the time when the intellectual world conception began. One could not have felt this beginning as progress if one had not believed that with thought one took possession of something that was more perfect than the old form of image experience. Of course, at this stage of thought development, this feeling was not clearly expressed. But what one now, in retrospect, can clearly state with regard to the ancient Greek thinkers was then merely felt. They felt that the pictures that were experienced by our immediate ancestors did not lead to the highest, most perfect, original causes. In these pictures only the less perfect causes were revealed; we must raise our thoughts to still higher causes from which the content of those pictures is merely derived.

Through progress into thought life, the world was now conceived as divided into a more natural and a more spiritual sphere. In this more spiritual sphere, which was only now felt as such, one had to conceive what was formerly experienced in the form of pictures. To this was added the conception of a higher principle, something thought of as superior to the older, spiritual world and to nature. It was to this sublime element that thought wanted to penetrate, and it is in this region that Pherekydes meant to find his three “Primordial Mothers.”

A look at the world as it appears illustrates what kind of conceptions took hold of a personality like Pherekydes. Man finds a harmony in his surroundings that lies at the bottom of all phenomena and is manifested in the motions of the stars, in the course of the seasons with their blessings of thriving plant-life, etc. In this beneficial course of things, harmful, destructive powers intervene, as expressed in the pernicious effects of the weather, earthquakes, etc. In observing all this one can be lead to a realization of a dualism in the ruling powers, but the human soul must assume an underlying unity. It naturally feels that, in the last analysis, the ravaging hail, the destructive earthquake, must spring from the same source as the beneficial cycle of the seasons. In this fashion man looks through good and evil and sees behind it an original good. The same good force rules in the earthquake as in the blessed rain of spring. In the scorching, devastating heat of the sun the same element is at work that ripens the seed. The “good Mothers of all origin” are, then, in the pernicious events also. When man experiences this feeling, a powerful world riddle emerges before his soul. To find the solution, Pherekydes turns toward his Ophioneus. As Pherekydes leans on the old picture conception, Ophioneus appears to him as a kind of “world serpent.” It is in reality a spirit being, which, like all other beings of the world, belongs to the children of Chronos, Zeus and Chthon, but that has later so changed that its effects are directed against those of the “good mother of origin.” Thus, the world is divided into three parts.

- The first part consists of the “Mothers,” which are presented as good, as perfect;

- the second part contains the beneficial world events;

- the third part, the destructive or the only imperfect world processes that, as Ophioneus, are intertwined in the beneficial effects.

For Pherekydes, Ophioneus is not merely a symbolic idea for the detrimental destructive world forces. Pherekydes stands with his conceptive imagination at the borderline between picture and thought. He does not think that there are devastating powers that he conceives in the pictures of Ophioneus, nor does such a thought process develop in him as an activity of fantasy. Rather, he looks on the detrimental forces, and immediately Ophioneus stands before his soul as the red color stands before our souls when we look at a rose.

Whoever sees the world only as it presents itself to image perception does not, at first, distinguish in his thought between the events of the “good mothers” and those of Ophioneus. At the borderline of a thought-formed world conception, the necessity of this distinction is felt, for only at this stage of progress does the soul feel itself to be a separate, independent entity. It feels the necessity to ask what its origin is. It must find its origin in the depths of the world where Chronos, Zeus and Chthon had not as yet found their antagonists. But the soul also feels that it cannot know anything of its own origin at first, because it sees itself in the midst of a world in which the “Mothers” work in conjunction with Ophioneus. It feels itself in a world in which the perfect and the imperfect are joined together. Ophioneus is twisted into the soul's own being.

We can feel what went on in the souls of individual personalities of the sixth century B.C. if we allow the feelings described here to make a sufficient impression on us. With the ancient mythical deities such souls felt themselves woven into the imperfect world. The deities belonged to the same imperfect world as they did themselves.

The spiritual brotherhood, which was founded by Pythagoras of Samos between the years 549 and 500 B.C. in Kroton in Magna Graecia, grew out of such a mood. Pythagoras intended to lead his followers back to the experience of the “Primordial Mothers” in which the origin of their souls was to be seen. It can be said in this respect that he and his disciples meant to serve “other gods” than those of the people. With this fact something was given that must appear as a break between spirits like Pythagoras and the people, who were satisfied with their gods. Pythagoras considered these gods as belonging to the realm of the imperfect. In this difference we also find the reason for the “secret” that is often referred to in connection with Pythagoras and that was not to be betrayed to the uninitiated. It consisted in the fact that Pythagoras had to attribute to the human soul an origin different from that of the gods of the popular religion. In the last analysis, the numerous attacks that Pythagoras experienced must be traced to this “secret.” How was he to explain to others than those who carefully prepared themselves for such a knowledge that, in a certain sense, they, “as souls,” could consider themselves as standing even higher than the gods of the popular religion? In what other form than in a brotherhood with a strictly regulated mode of life could the souls become aware of their lofty origin and still find themselves deeply bound up with imperfection? It was just through this feeling of deficiency that the effort was to be made to arrange life in such a way that through the process of self-perfection it would be led back to its origin. That legends and myths were likely to be formed about such aspirations of Pythagoras is comprehensible. It is also understandable that scarcely anything has come down to us historically about the true significance of this personality. Whoever observes the legends and mythical traditions of antiquity about Pythagoras in an all-encompassing picture will nevertheless recognize in it the characterization that was just given.

In the picture of Pythagoras, present-day thinking also feels the idea of the so-called “transmigration of souls” as a disturbing factor. It is even felt to be naive that Pythagoras is reported to have said that he knew that he had already been on earth in an earlier time as another human being. It may be recalled that that great representative of modern enlightenment, Lessing, in his Education of the Human Race, renewed this idea of man's repeated lives on earth out of a mode of thinking that was entirely different from that of Pythagoras. Lessing could conceive of the progress of the human race only in such a way that the human souls participated repeatedly in the life of the successive great phases of history. A soul brought into its life in a later time as a potential ability what it had gained from experience in an earlier era. Lessing found it natural that the soul had often been on earth in an earthly body, and that it would often return in the future. In this way, it struggles from life to life toward the perfection that it finds possible to obtain. He pointed out that the idea of repeated lives on earth ought not to be considered incredible because it existed in ancient times, and “because it occurred to the human mind before academic sophistry had distracted and weakened it.”

The idea of reincarnation is present in Pythagoras, but it would be erroneous to believe that he — along with Pherekydes, who is mentioned as his teacher in antiquity — had yielded to this idea because he had by means of a logical conclusion arrived at the thought that the path of development indicated above could only be reached in repeated earthly lives. To attribute such an intellectual mode of thinking to Pythagoras would be to misjudge him. We are told of his extensive journeys. We hear that he met together with wise men who had preserved traditions of oldest human insight. When we observe the oldest human conceptions that have come down to us through posterity, we arrive at the view that the idea of repeated lives on earth was widespread in remote antiquity. Pythagoras took up the thread from the oldest teachings of humanity. The mythical teachings in picture form appeared to him as deteriorated conceptions that had their origin in older and superior insights. These picture doctrines were to change in his time into a thought-formed world conception, but this intellectual world conception appeared to him as only a part of the soul's life. This part had to be developed to greater depths. It could then lead the soul to its origins. By penetrating in this direction, however, the soul discovers in its inner experience the repeated lives on earth as a soul perception. It does not reach its origins unless it finds its way through the repeated terrestrial lives. As a wanderer walking to a distant place naturally passes through other places on his path, so the soul on its path to the “mothers” passes the preceding lives through which it has gone during its descent from its former existence in perfection, to its present life in imperfection. If one considers everything that is pertinent in this problem, the inference is inescapable that the view of repeated earth lives is to be attributed to Pythagoras in this sense as his inner perception, not as something that was arrived at through a process of conceptual conclusion.

Now the view that is spoken of as especially characteristic of the followers of Pythagoras is that all things are based on numbers. When this statement is made, one must consider that the school of Pythagoras was continued into later times after his death. Philolaus, Archytas and others are mentioned as later Pythagoreans. It was about them especially that one in antiquity knew they “considered things as numbers.” We can assume that this view goes back to Pythagoras even if historical documentation does not appear possible. We shall, however, have to suppose that this view was deeply and organically rooted in his whole mode of conception, and that it took on a more superficial form with his successors.

Let us think of Pythagoras as standing before the beginning of intellectual world conception. He saw how thought took its origin in the soul that had, starting from the “mothers,” descended through its successive lives to its state of imperfection; Because he felt this he could not mean to ascend to the origins through mere thought. He had to seek the highest knowledge in a sphere in which thought was not yet at home. There he found a life of the soul that was beyond thought life. As the soul experiences proportional numbers in the sound of music, so Pythagoras developed a soul life in which he knew himself as living in a connection with the world that can be intellectually expressed in terms of numbers. But for what is thus experienced, these numbers have no other significance than the physicist's proportional tone numbers have for the experience of music.

1917-11-02-GA273

is the main lecture, titled 'Faust and the “Mothers”'

1923-06-24-GA277

We know that once Earth and sun were one body. Of course this is long ago, during the Old Saturn and Old Sun stages of evolution.

Then there was also a short repetition of those periods during the Earth stage.

But something remains behind which still belongs there. And this we bring forth again today. And we bring it forth from the repetitious Condition on Earth not only by heating our rooms with coal, but we bring it forth by using electricity. For, what remains from those times after Old Saturn and Old Sun, when the sun and Earth were one, that provided the basis for what we have today on earth as electricity. We have in electricity a force which is sun-force, long connected with the Earth, a hidden sun-force in the Earth. … Electric light is actually light retained from Old Sun.

1923-12-14-GA232

Look around at the metallic nature in the earth today. It is crystallized and surrounded with a kind of crust which comes from the earth. The metal-nature streamed in from the cosmos, and that which comes from the earth received lovingly that which streamed in from the cosmos. You see this everywhere if you go to metal-mines and take an interest in them.

That which received the metal was called the Mother. The most important of these earthly substances which, as it were, came forward to meet the heavenly metal-element in order to take it up were called “the Mothers.”

That is only one aspect of “The Mothers” to whom Faust descends. He descends at the same time into those pre-earthly periods of the earth, in order to see there how the Mother-earth takes into herself what is given by the Father-element in the cosmos.

Discussion

Related pages

- Force substance representation

- Spectrum of elements and ethers

- Formative forces

- Planes or worlds of consciousness

- The elementary kingdoms

- Radioactivity

- Greek mythology