Holy Grail

The Holy Grail refers to:

- a legend about the path of the physical chalice used at the Last Supper

- made from a stone that fell from Lucifer's crown

- the symbolic secret or Mystery of the Grail in the connection between the up-springing of all the budding new life of nature and the death of Christ on the Cross, more specifically the Christ-I in the blood of Christ Jesus

- a medieval story and work of art, most known in the versions written by von Eschenbach and de Troyes

- and in popular media, the search for the Grail represents Man's quest for the valuable and desired higher being.

- points 2 and 4 above are linked to the esoteric meaning of the grail as the receiving chalice consisting of the purified astral body or spirit-self that is approached and filled by the life-spirit (through the Christ Impulse). See 'essence of the grail' in Aspects section 2.3

.

The Holy Grail therefore does not just have one meaning, it represents both a cosmic aspect relevant for the development of humanity and related to the Christ Impulse, the related physical-scientific and physiological aspects to this (as in transsubstantiation, pineal gland, higher ethers, ..) , as also a medieval epic that has known centuries of storytelling in so many artistic versions.

Whereas a person might not care or be interested in the storyline, the two first are universal aspects that concern the whole of mankind.

See schema FMC00.118A below for these various dimensions or aspects [1] and [2.1] to [2.5]

Introductory quotes

From 1909-04-11-GA109 (SWCC rephrased concisely)

The Brotherhood of the Holy Grail is a brotherhood of initiates that was formed to preserve the secret of the I of Christ and its deep Mystery. Its founder took the chalice that Christ Jesus had used at the Last Supper and collected in it the blood that dripped from the wounds of the Savior when He was hanging on the cross. By collecting the blood of Christ Jesus, he collected an expression and copy of the Christ-I. This chalice was kept in a holy place and the Brothers of the Holy Grail kept the Mystery of the Christ-I in the brotherhood through the centuries, seeing to it that humanity matured slowly to the point where some individuals could accept copies of the I of Christ Jesus. Today the time has come when these secrets can be revealed because the hearts of human beings can become ripened through spiritual life to an extent where they elevate themselves to an understanding of this great mystery. This mystery is a reality.

Aspects

- the Grail is “that holy bowl, in which Christ took the Last Supper, in which Joseph of Arimathia caught Christ’s blood when it flowed on Golgotha. This blood, enclosed in such a bowl, was brought to a holy place.” (1909-05-06-GA057)

[2.1] - Grail storyline - exoteric story, characters and adventures

- relationship with the Arthur stream, and the Parsifal story, for a positioning overview see: Christ Module 6 - Principle in image and story

- the Castle of the Holy Grail as a Mystery site and initiation center, with the Grail knights (also: Templeisen, Knights of the Swan)

[2.2] and [2.3] - the symbolic meaning of the story and the experiences by the main characters:

- Titurel

- the first Grail king and great-grandfather of Parsifal

- King Titurel was the reincarnation of the lofty initiate (see the legend of Flor and Blancheflor, inspired by Titurel, who also inspired Charlemagne) (1909-08-27-GA266/1)

- As legend tells it, the chalice in which Joseph of Arimathea caught Christ-Jesus' blood was removed to Europe, preserved by angels in a region high above the surface of the Earth until the arrival of Titurel who created for this sacred chalice of the Grail a temple on Mont Salvat. (1921-04-16-GA204, see Reconquista#1921-04-16-GA204)

- Lohengrin

- Lohengrin or the swan-knight is a messenger the the White Brotherhood or Grail Lodge, who in the Middle Ages prepared the way for the establishment of towns, a new impulse to enter human civilisation and consciousness of the middle classes. He was an initiate of the third grade, with the swan as his symbol. He must not be asked any questions, for it is a profanation and misunderstanding to ask questions to an initiate concerning occult matters. (see also commentary on Richard Wagner's opera 1905-03-28-GA092)

- Elsa of Brabant personifies the medieval soul and represents the consciousness of the materialistic civic sense. The human soul is always presented in mysticism as feminine.

- enemies of the grail (see Schema FMC00.115 below)

- Klingsor

- Kundry, the tempress of the lower nature

[2.3] - spiritual scientific view (processes, physiology, symbolism)

- essence of the Grail

- see Kundalini#Note 3 - The process of illumination

- the grail refers to the receiving chalice consisting of the purified astral body (or spirit-self, or manas in theosophy, or Virgin Sophia in esoteric Christianity) that is approached and filled by the life-spirit (or buddhi in theosophy, or Holy Spirit in esoteric Christianity). See also illustration on Schema FMC00.468. This union is than also referred to as the 'chemical marriage' or 'immaculate conception'. All this has to be regarded as spiritual and non referring to the mineral physical human body.

- see Kundalini for the explanatory background and links to the overview Schema FMC00.354 (see also below)

- see Kundalini#Note 3 - The process of illumination

- Ganganda Greida: 'food for spiritual travellers'

- see the link with etherization of blood, and the process between heart and brain.

- through the breathing process, the astral-etheric streams (see FMC00.015 on Human breath) get into the heart's two blood circuits via the lungs

- the name of the Grail in the stellar script (1914-01-02-GA149, see Schema FMC00.116 below)

- the three stages through which the soul of Man passes (1909-05-06-GA057)

- 1 - stage of 'stupor' (Dumpfheit) of the soul: the soul is caught up in matter and material perception, allows matter to say what is truth.

- 2 - stage of 'doubt' (Zwifel): the soul recognizes that the outer world offers only illusion

- 3 - stage of 'blessedness' (Saelde, Seligkeit): the soul rises to life in the spiritual worlds.

[2.5] - Grail literature and versions

- see below, and Barber under 'Further reading' below

[2.6] - Grail historical research

- timing of the facts: "around the turn from the eight to the ninth century" (re: W.J. Stein)

- location of the grail castle of Monsalvat in Northern Spain

- 'Munsalvaesche' mystery site of the holy grail (1921-04-16-GA204) in Northern Spain (1906-07-29-GA097)

- "it is no accident that the Grail was to be found in Spain, where one had to go virtually miles away from what the earthly offered, where one had to break through thorny hedges in order to penetrate to the spiritual temple that enclosed the Grail" (1921-04-16-GA204)

- Rudolf Steiner have precise indications about the location of the grail castle to Ilona Shubert (re: Manfred Schmidt-Brabant (2003, lecture 3) - see Further reading below)

- the two first grail castles lay in the mountains called Sierra de la Demanda (located east of Burgos in Northern Spain); timing "around the turn from the eight to the ninth century"

- it is suggested that the second grail castle may have been San Millan de Susa. Then the onyx cup leaves for San Juan de la Pena, the Grail goes to Monsegur where the castle was built to protect the Grail (1204); but Montsegur is destroyed as a result of the catastrophe of the Cathars.

[2.7] - esoteric symbols

- Schema FMC00.116 (sun and moon), Schema FMC00.191 and Schema FMC00.191A (transubstantiation and monstrance).

- [2.2] is focused on symbols in the storyline of the medieval epic, that is however only one perspective to the Holy Grail. As a concept or theme, it is universal for humanity, much beyond this storyline alone.

Other

- stone from Lucifer's crown -> grail cup

- "the legend tells that a stone fell out of Lucifer's crown when he fell from heaven, and that this stone was worked into the Grail Cup, the sacred and noble chalice in which the blood of Christ was caught at Golgotha" (1912-05-07-GA265) and "When at the beginning of our evolution Lucifer fell from the ranks of those Spirits who guide humanity, a precious stone dropped from his crown. This stone was the cup from which Christ Jesus drank with His disciples at the Last Supper and in which the blood flowing on Golgotha was received. "(1907-12-02-GA092) - also on other lectures such as 1909-08-23-GA113 below

- this stone which fell from Lucifer's crown is the full power of the I (1909-08-23-GA113)

- positioning: a continuation of the European Mystery School tradition of the Northern stream, Druidic and Trotten mysteries and Colchis mysteries, to be superseded with the Rosecrucian teachings from the 14th century onwards.

- legend of Flor and Blancheflor (1909-05-06-GA057)

- The event recorded in the legend of the Holy Grail is also described in the legend of Flor and Blancheflor. It was given poetic form by Conrad Fleck in 1230, and deals with the Initiation [process] of the Knights of the Grail or the Templars

- Flor and Blancheflor must not be thought of as outer figures, but correspond to 'the flower with red petals' (the rose) and 'the flower with white petals' (the lily)

- Flore, the rose: is symbol for the human soul who received the impulse of the I, of Personality, who lets the spiritual work out of his Individuality, who has brought the I-force down into the red blood. The principle of self-consciousness has entered wholly

- Blanchelor, the lily: is symbol for the soul who can only remain spiritual when the I remains outside. The lily symbolises the soul which finds its higher I-hood.

- The union of the lily-soul with the rose-soul was taken to express that principle in Man which can link him with the Mystery of Golgotha. Flor and Blancheflor symbolise the finding of the the World-I by the human I, as there was a union between the soul that is within and the soul that as the World-Spirit pervades the universe outside.

- Prester John

- as a " continuation of the Parsifal saga ... when the Grail became invisible in Europe, it was carried to the realm of Prester John" which is "not to be found on Earth" (1914-01-02-GA149). This may refer to the Grail not visible in Europe as the Christ Impulse is working below the human Waking consciousness.

Inspirational quotes

1909-GA013

.. the highest imaginable ideal of human evolution results from the 'knowledge of the Grail': the spiritualization that Man acquires through his own efforts.

.. this spiritualization appears .. as result of the harmony that Man produces in the fifth and sixth cultural ages between the acquired powers of intellect and feeling and the knowledge of the supersensible worlds.

What he there produces in the inmost depths of his soul is finally itself to become the outer world. The human spirit elevates itself to the tremendous impressions of its outer world and first divines and afterwards recognizes spiritual beings behind these impressions; Man's heart feels the boundless sublimity of the spiritual. The human being can also recognize that his inner experiences of intellect, feeling, and character are the indications of a nascent world of the spirit.

1909-04-11-GA109

and thus the secret had to be found of how this I could be preserved in complete silence and profound mystery, until the appropriate moment in human and Earth evolution. For this purpose a brotherhood of initiates was formed to preserve this secret: the brotherhood of the Holy Grail.

Main aspects

[2.1] - Grail storyline - exoteric story, characters and adventures

Introduction

One aspect of the legend of the Grail is that the Grail is the physical chalice from which Christ-Jesus drank at the Last Supper, and in which Joseph of Arimathaea gathered some of the blood that flowed from His wounds on the Cross. This chalice was cut from a particularly precious stone from Lucifer's crown when it was struck by Michael's sword of light during the battle waged in the spiritual world between Lucifer and Michael.

In one version the chalice through various travels would have landed on the island of Avalon (near current Glastonbury).

[2.2] and [2.3] - the symbolic meaning of the story and the experiences by the main characters:

White magic of the Tempeleisen or Knights of the Holy Grail

The earliest legend appears at the turning-point of the Middle Ages: the grail of Christ Jesus is moved from Titirel to castle Spain Monsalvat in Spain, where it is garded by twelve knights.

Now the Templars mysteries of those times were called Tate Gothic mysteries, and their initiates were called Tempelisen or Tempeleisen or Knights of the Holy Grail.The Tempeleisen represented the inner, the true Christianity - in contrast with the Christianity of the Churches.

Lohengrin represents one of these Knights of the Holy Grail, a great initiate the Swan of the third degree of discipleship.

The Swan in Grail stories is a symbol for an initiate who can see into the higher spirit world and passes to a sphere beyond the world of stars from where the initiate experiences the Logos as the primal source of the universe. Such initiate is permeated fully with the Christ principle and whose ether-body which has become Life-Spirit. By this ether-body he is borne upwards to the higher spirit world where the laws of space and time do not hold sway. The Swan is the symbol of this ether body who bears Lohengrin over the sea in a boat (the physical body, regarded purely as an instrument) over the material world.

- This in contrast to: King Arthur and Round Table (Wales), see Arthur Stream

The productive power that shows itself in the flower chalice of the plant, going up through the other realms, is the same as in the Holy Grail. It merely has to go through purification in the purest, noblest form of Christianity, as we see it in Parsifal.

Black magic of Klingsor

Klingsor his a black magician in opposition of the Templars. Klingsor and temptress Kundry (modern Herodias) represent the enemies of the knighthood of the Holy Grail. Klingor has not destroyed desire, but only the organ of desire.

He represents a form of Christianity coming from the South and that introduced an ascetic life as a way to eliminate a sensual life. However this could not destroy desire, and thereby was unable to reach a higher spiritual knowledge.

Here is a link with degenerated mysteries and Black magic (see 1906-07-29-GA097).

[2.5] - Grail literature and versions

The storyline of the quest for the grail exists in many versions in the various european cultures. Rudolf Steiner mostly (always) refers to the two earliest versions of Chrétien de Troyes and Wolfram von Eschenbach (whom he calls an inspired initiate)

It is important to realize that some 5-10 main versions exist from the period 1180-1240, and that over the centuries the Grail story became part of the cultural heritage, with continuous renewal by new authors. An example is Sir Thomas Malory (Morte Darthur, 1470), or Wagner's opera's Lohengrin, Parsifal.

The 13th century version

- Wolfram von Eschenbach (1160/80-1220) largely adapted this story which is dated to the first quarter of the 13th century.

- Chrétien de Troyes (late 12th century) is the poet of the Grail romance 'Conte del Graal' (or 'Perceval, the Story of the Grail'), written in Old French during the 1180s or 1190s , but (probably) left it incomplete.

- Chrétien de Troyes (late 12th century) wrote the Grail romance 'Perceval, the Story of the Grail' in Old French during the 1180-1190s , but (probably) left it incomplete.

- as a result, there were 'continuations' written which greatly expanded the base work, and various versions exist

- First continuation (est. 1190-1200)

- Second continuation (est. 1200-1210)

- Third continuation (est. 1210-1220), by Manessier

- Fourth continuation (est. 1226-1230), by Gerbert de Montreuil

- as a result, there were 'continuations' written which greatly expanded the base work, and various versions exist

- Wolfram von Eschenbach (1160/80-1220) largely adapted this story which is dated to the first quarter of the 13th century (est. 1210-1220)

- von Eschenback refers not to de Troyes, but by a poet called Kyot, and a manuscript by Flegetanis

- English versions (see Note [1] in the Discussion area below)

- by Jessie L. Weston: 'Parzival: A Knightly Epic' (1894)

- Helen M. Mustard and Charles E. Passage; 'Parzival: A Romance of the Middle Ages' (1961)

- A. T. Hatto: 'Parzival' (1980)

- Cyril Edwards: 'Parzival: With Titurel and the Love Lyrics' (2004)

Furthermore other important versions are:

- Robert de Boron (est. 1200-1210)

- Romance of the history of the grail (before: Joseph of Arimathea), Merlin, Perceval

- the 'Lancelot-Grail' or 'Vulgate' cycle (est. 1210-1250)

- Lancelot, Quest of the Holy Grail, History of the Holy Grail, Romance of the Grail

- new versions have appeared in French by oa by Oskar Sommer (1908-1916), Daniel Poirion (2001-2009), and in English oa by Norris J. Lacy (1992-1996),

- Perlesvaus - High book of the Grail (est. <1210)

[2.6] - Grail historical research

Timing of the Grail narrative

Rudolf Steiner said that the Grail narrative was made exoteric about the year 1180, but the grail stories had been present in the souls of men since the eight or ninth century.

W.J. Stein quotes from a visit by Rudolf Steiner to his class on 1923-01-16 where he dates the story to the eight or ninth century, times of bloodshed, armour and fighting in the wild forests. The knights sought to establish, in this bloodthirsty age, an order that was based on bloodshed. The central body of these knights, who were scattered about everywhere, was formed by the Knights of King Arthur with centres in England and Northern France.

location

- of the grail castle of Monsalvat in Northern Spain

Illustrations

Schema FMC00.118A: is an extended version of Schema FMC00.118 that provides an overview with numbered sections to structure the different logical perspectives from which one can study the subject of the Holy Grail. Click to enlarge.

Addition (to be added): on the right will be [2.7] called 'esoteric symbols', and this includes pointers to Schema FMC00.116 (sun and moon), Schema FMC00.191 and Schema FMC00.191A (transubstantiation and monstrance). In contrast, [2.2] is focused on symbols in the storyline.

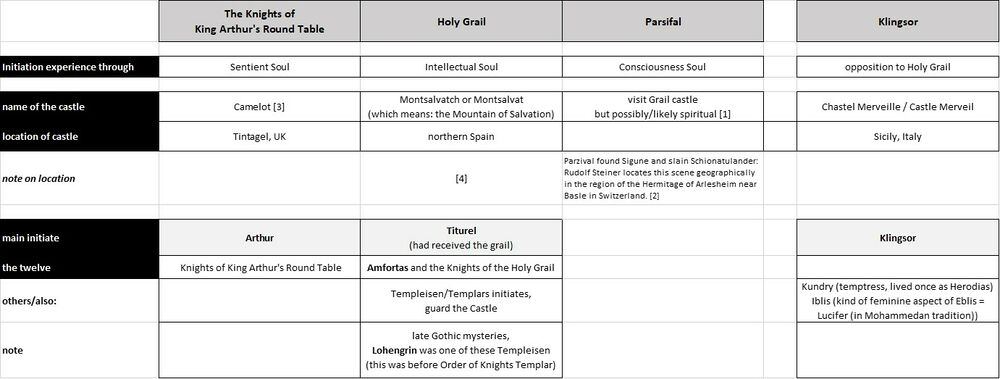

Schema FMC00.114 is an overview table with the key names for the three stories, and the link to the threefold soul (see 1913-02-07-GA144)

Schema FMC00.354 is a meta study schema, using other schemas as infographics to show a broader scope and the relationship between related aspects. Not all schema or lecture references are given, these can be found on the various pages such as Kundalini, Ganganda Greida, Etherization of blood and related pages. Central theme is the symbolism of the Holy Grail, with on the one hand the grail cup and the bloody lance, and on the other hand the pituitary and pineal gland. The diagram relates the physiological and spiritual processes taking place in Man, with the central role of the blood as the carrier of the Human 'I', and the human heart.

Note: the schema also shows why the Grail is sometimes drawn with the cup downwards, for example on the seventh apocalyptic seal (Schema FMC00.259 on Book of Revelation), see also Schema FMC00.270A on Christ Module 6 - Principle in image and story

Schema FMC00.270B is an illustration from 1906-07-27-GA244 Q&A 105.3, which depicts the same as the composition Schema FMC00.270A on the basis of Schema FMC00.270 on Christ Module 6 - Principle in image and story. Drawing made by Rudolf Steiner, recorded by Mathilde Scholl in a private conversation.

Schema FMC00.116 shows the symbol for Good Friday and Easter: the spiritual sun in the physical sun.

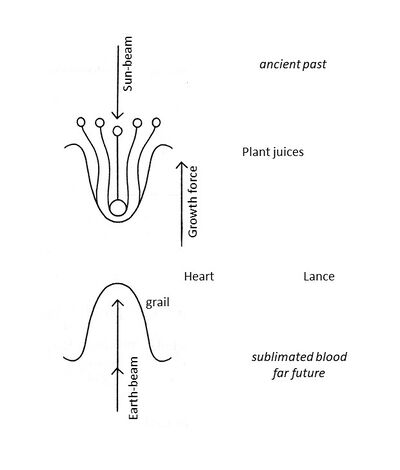

Schema FMC00.110 depicts the metaphoric imagery of:

- the sunray and the flower chalice .. how the plant takes the energy (and higher ethers) contained in the light of a sunray

- the symbol of the spear and cup directly relating to the same image

Schema FMC00.115 sketches the counterforces of Klingsor, Iblis and Kundry and their contextual story.

This is not purely a symbolic story but the characters and locations have a true historical basis. In other lectures Rudolf Steiner points out Sicily is still regarded as a center of evil influences that is even noticeable in the aura. Then again the Etna has a special (positive) esoteric meaning to, see ao Johanna von Keyserlinck and the story of Empedocles.

Artwork

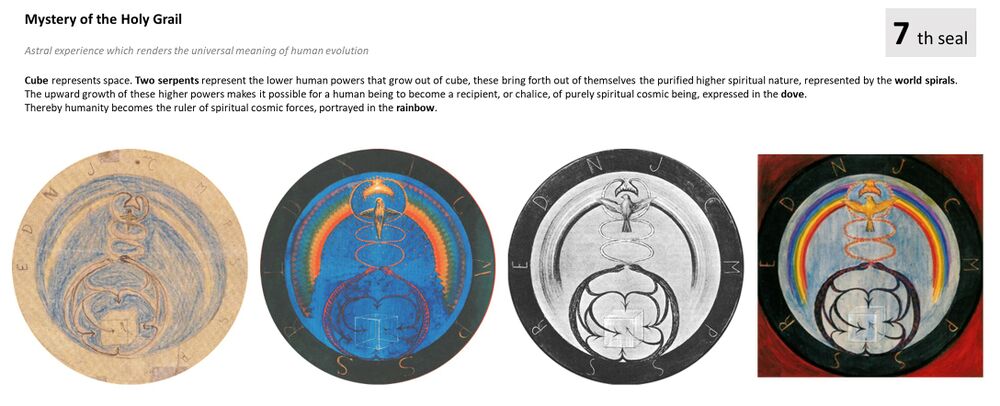

Schema FMC00.259: depicts the seventh apocalyptic seal from the Book of Revelation, representing the Mystery of the Holy Grail and the future state of the human being

- The cube represents a transparent diamond cube made of pure carbon. Man will create the cube when he has progressed to the point where he uses carbon itself to build his body. This cube of crystallized pure carbon is the best indication of the future state of man.

- See Christ Module 6 - Principle in image and story#Philosopher's stone - plant metaphor - teachings of carbon.

- Man will have progressed so far that he will rise above the physical dimensions of space but also recognize the oncoming contra-dimensions of the etheric formative forces. See also: mathematics of the etheric

- The serpents signify the upward development to the higher. The luminous coils and serpent symbolizes the devoted nature of knowledge, required to grasp the world spiral in the Caduceus, which will then be fiery, which winds itself out of pure knowledge, and then transforms into the downward-pointing pure chalice.

- The grail cup is represented with the chalice turned downward. The chalice of the plant or 'cup' is today directed openly upwards, pure and chaste. With the human being it is reversed. In the future the human cup will become chaste and will turn itself downward; hence is the Grail shown here as a chalice turned downward. Ssee Schema FMC00.270 and variants on on Christ Module 6 - Principle in image and story.

- The dove represents the human being who has become purely spiritual and innocent

- The rainbow indicates the sevenfold creative Man that becomes rules over spiritual cosmic forces.

- The characters around the seal refer to the Rosicrucian 'Ex Deo Nascimur (EDN) • In Christo Morimur (ICM) • Per Spiritum Sanctum Reviviscimus (PSSR)'. See: EDN - ICM - PSSR.

Schema FMC00.355 is an illustration from Manly P. Hall's (1901-1990) work 'Secret teachings of all ages' (1928)

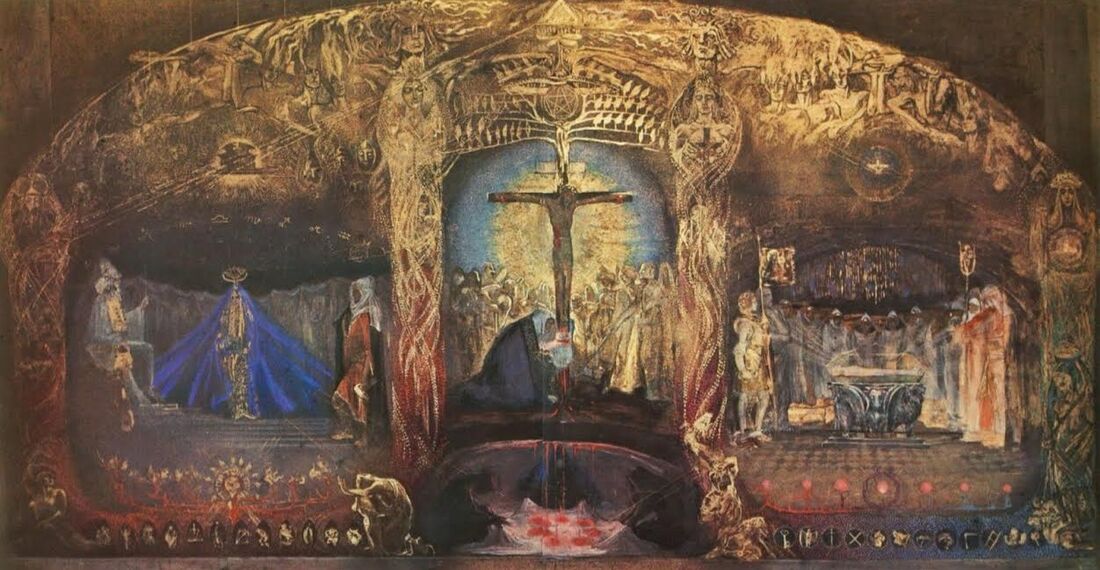

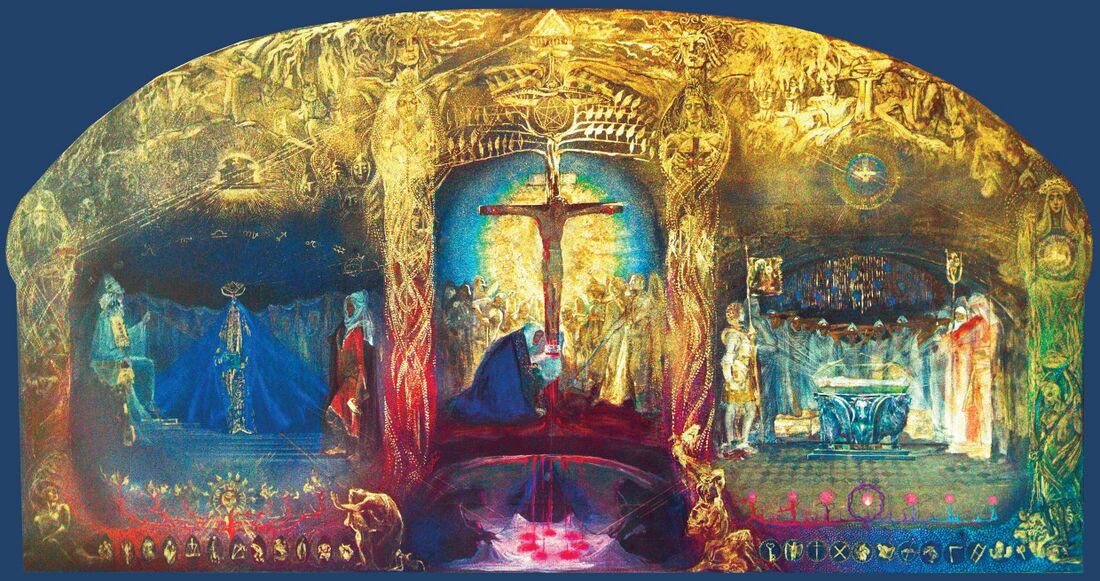

Schema FMC00.700: shows the Grail triptych by Anna May - von Rychter (1864–1955), a painting of approx. 2.5 by 6 meters painted at the time of the Munich mystery dramas (1909-13), and commissioned by Rudolf Steiner and based on his detailed instructions.

The work was originally planned for the Johannesbau in Munich and later intended for the first Goetheanum, but it was later given to the Hamburg Waldorf School and later destroyed there by bombings during WW2. It was exhibited in Munich in 1918 with the title 'Grail - Divine and Human Blood'; the work is sometimes also referred to as 'From Solomon through Golgotha to Christian Rosenkreutz'.

The left panel shows the three main figures of the Temple legend: King Solomon, Hiram Abiff and the Queen of Sheba.

The central panel depicts the Mystery of Golgotha, with Joseph of Arimathea catching the blood of Christ in the Grail chalice.

The right panel shows the initiation of Christian Rosenkreutz in the 13th century, described by Rudolf Steiner in 1911-GA130

Schema FMC00.700A: shows a high resolution version of the Grail triptych by Anna May - see original Schema FMC00.700, rendered for higher contrast and color. It can be used to study the details on each of the three panels.

Literature includes:

- Margareth Hauschka: 'Das Triptychon Gral von Anna May' (1975 in Das Goetheanum)

- Adrian Anderson: 'Rudolf Steiner's Esoteric Christianity in the Grail painting by Anna May' (2017)

Lecture coverage and references

1905-05-19-GA092

The fifth root-race [the current fifth cultural age] arose out of the ancient [Atlantean] Semitic races. A trace of this origin still lives in all the sub-races which have so far constituted the fifth root-race. ... Thus the primal semitic impulse reaches as far as the fifth sub-race or cultural age. We see the impulses of one great stream penetrate five times into the earliest civilisations.

We have one great spiritual stream coming from the South, which is met by another stream arising in the North, which penetrates into four phases of the early northern civilisation and develops until it meets the first stream, thus flowing together with it.

A childlike, unworldly nation dwelt in northern Europe and these early inhabitants underwent the influence of the stream of culture coming from the South at the turning point of the 12th and 13th century. This new culture penetrated into these regions like a spiritual current of air. Wolfram von Eschenbach was entirely under the influence of this spiritual current.

The northern civilisation is symbolized in the legend of Tannhäuser, which also contains an impulse from the South. Everywhere we come across something which may be designated as a semitic impulse.

1907-12-18-GA068A

see longer quote on: Four kingdoms of nature#1907-12-18-GA068A

and see also Symbol of rose cross which depicts this

Now look into the future, when the human being will have transformed himself. He will have purified the impure, desire-filled fleshly substance; human nature will become pure and chaste again. Then the lower organs of desire will have fallen away, he will be equipped with higher organs and a higher consciousness, and he will stretch out his pure, chaste organs of fertilization towards the spiritual sunbeam of the holy love lance.

He who can look into the process of world evolution knows: There are organs in the human body that will wither away, that will wither away, and those that will be developed higher and higher, that will bring forth similar things in a pure and chaste manner, equipped with a higher consciousness.

This real ideal, which stands before the eyes of the human being as a disciple, as something that will truly reach all of humanity, gives a different concept of development than abstract concepts. When we turn to this real ideal, which is called the Holy Grail, when we survey this development, then we pursue such a development not only with thoughts, not only with the mind, but our feelings are carried away. Shivers run through the one who follows the course of human development in this way, and what we then feel is something that passes like a breath through the soul. Then we develop inner organs in our soul and new worlds appear to us – through such intimate processes of the inner being, the spiritual organs are awakened. As thinking was developed before, so now feeling is developed.

1909-04-11-GA109

The external expression for the I is the blood. That is a great secret, but there have always been human beings who were acquainted with it and who were aware of the fact that copies of the I of Jesus of Nazareth are present in the spiritual world. And since the Event of Golgotha, there have always been human beings through the centuries who had to see to it that humanity matured slowly to the point where some individuals could accept copies of the I of Jesus Christ, just as some human beings received copies of His etheric or astral body.

A secret way had to be found to preserve this I in a silent, deep Mystery until the time when a suitable moment for its use would be at hand. To preserve this secret, a brotherhood of initiates was formed: The Brotherhood of the Holy Grail. This brotherhood goes back to the time when, as is reported, its founder took the chalice that Christ Jesus had used at the Last Supper and collected in it the blood that dripped from the wounds of the Savior when He was hanging on the cross. This founder of the brotherhood collected the blood of Christ Jesus, the expression and copy of His I, in the chalice that is called the Holy Grail. It was kept in a holy place, in the brotherhood, that through its institution and initiation rites comprised the Brothers of the Holy Grail.

Today the time has come when these secrets can be revealed because the hearts of human beings can become ripened through spiritual life to an extent where they elevate themselves to an understanding of this great mystery. If Spiritual Science can kindle souls so that they warm up to an engaged and lively understanding of such mysteries, these very souls will become mature enough, through casting a glance at that Holy Grail, to get to know the mystery of the Christ-I — the eternal I into which any human I can be transformed. This mystery is a reality. All that people have to do is to follow the call by spiritual science to understand this mystery as a given fact so that they can receive the Christ-I at the mere sight of the Holy Grail. To accomplish this, it is necessary only that one understand and accept these happenings as fact.

alternative translation

and thus the secret had to be found of how this I could be preserved in complete silence and profound mystery, until the appropriate moment in human and Earth evolution. For this purpose a brotherhood of initiates was formed to preserve this secret: the brotherhood of the Holy Grail.

1909-05-06-GA057

is a lecture on the origin of Mystery Schools in Europe, see also Druidic and Trotten mysteries#1909-05-06-GA057

[Later: Holy Grail]

This quest of the soul for the highest was called by the outer world in later times: The secret of the Holy Grail. And the Parsifal or Grail legend is simply a form of the Christ Mystery. The Grail is the holy Cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper and in which Joseph of Arimathea caught the blood as it flowed on Golgotha. The Cup was then taken to a holy place and guarded.

So long as a Man does not ask about the invisible, his lot is that of Parsifal. Only when he asks, does he become an Initiate of the Christ Mystery.

Wolfram von Eschenbach speaks in his poem of the three stages through which the soul of man passes.

- The first of these is the stage of outer, material perception. The soul is caught up in matter and allows matter to say what is truth. This is the “stupor” (Dumpfheit) of the soul, as Wolfram van Eschenbach expresses it.

- And then the soul begins to recognise that the outer world offers only illusion. When the soul perceives that the results of science are not answers but only questions, there comes the stage of “doubt” (Zwifel), according to Wolfram von Eschenbach.

- But then the soul rises to “blessedness” (Saelde, Seligkeit) — to life in the spiritual worlds.

These are the three stages.

[Initiation and separation of TFW]

The Mysteries which were illuminated by the Christ Impulse have one quite definite feature in common whereby they are raised to a higher level than that of the more ancient Mysteries. Initiation always means that a Man attains to a higher kind of sight and that his soul undergoes a higher development. Before he sets out on this path, three faculties live within his soul: thinking, feeling and willing. He has these three soul-powers within him. In ordinary life in the modern world, these three soul-powers are intimately bound together. The I of Man is interwoven with thinking feeling and willing because before he attains Initiation he has not worked with the powers of the I at the development of his higher members.

- The first step is to purify the feelings, impulses and instincts in the astral body. Out of the purified astral body there rises the spirit-self or manas.

- Then Man begins to permeate every thought with a definite element of feeling so that each thought may be said to have something ‘cold’ or ‘warm’ about it. — He is transforming his ether-body or life-body. Out of the transformed ether-body (it is a transformation of feeling), arises budhi or life-spirit.

- And finally, he transforms his willing and therewith the physical body itself, into atma or spirit-Man.

Thus by transforming his thinking, feeling and willing, man changes his astral body into spirit-self, his ether-body into life-spirit and finally his physical body into spirit-Man. This transformation is the result of the Initiates systematic work upon his soul, whereby he rises to the spiritual worlds.

But something very definite happens when the path to Initiation is trodden in full earnest and not light-heartedly. In true Initiation it is as if a Man's organisation were divided into three parts, and the I reigns as king over the three. Whereas in ordinary circumstances the spheres of thinking, feeling and willing are not clearly separated, when a Man sets out on the path of higher development thoughts begin to arise in him which are not immediately tinged with feeling but are permeated with the element of sympathy or antipathy according to the free choice of the I. Feeling does not immediately attach itself to a thought, but the Man divides, as it were, into three: he is a Man of feeling, a Man of thinking, a Man of will, and the I, as king, rules over the three.

At a definite stage of Initiation he becomes, in this sense, three men. He feels that by way of his astral body he experiences all those thoughts which are related to the spiritual world; through his ether-body he experiences everything that pervades the spiritual world as the element of feeling; through his physical body he experiences all the will-impulses which flow through the spiritual world. And he realises himself as king within the sacred Three. A Man who is not able or ripe enough to bear this separation of his being, will not attain the fruits of Initiation. The sufferings that crowd upon him in his immature state will keep him back. A Man who approaches the Holy Grail but is not worthy, will suffer as Amfortas suffered. He can only be redeemed by one who brings the forces of good. He is freed from his sufferings by Parsifal.

And now let us return once more to what Initiation brings in its train. The seeking soul finds the spiritual world; the soul finds the Holy Grail which has now become the symbol of the spiritual world. Individual Initiates have experienced what is here described. They have gone the way of Parsifal, have become as kings looking down on the three bodies. The Initiate says to himself: ‘I am king over my purified astral body which can only be purified when I strive to emulate Christ.’ He must not hold to any outer link, to anything in the external world, but unite himself in the innermost depths of his soul with the Christ Principle. Everything that binds him with the world of sense must fall away in that supreme moment. Lohengrin is the representative of an Initiate. It is not permitted to ask his name or rank, in other words, what connects him with the world of sense. He who has neither name nor rank, is called a ‘homeless’ Man. Such a Man is permeated through and through with the Christ Principle. He too looks down on the ether-body which has become Life-Spirit, as upon something that is now separate from the astral body. By this ether-body he is borne upwards to the higher worlds, where the laws of space and time do not hold sway. The symbol of this ether-body and its organs, is the Swan who bears Lohengrin over the sea in a boat (the physical body), over the material world. The physical body is felt to be an instrument.

The soul on earth who experiences a new impulse through Initiation is symbolised in the figure of Elsa von Brabant. This shows us the sense in which the Lohengrin legend — which has many other meanings as well — is a portrayal of Initiation in the Mysteries associated with the Holy Grail. Thus in the eleventh to the thirteenth century, these secrets of the Holy Grail were taught in connection with the Christ Mystery. The Knights of the Grail were the later Initiates. They were confronted in the world with an exoteric Christianity, whereas esoteric Christianity was cultivated in the Mysteries. And in the Mysteries, men sought to find that relation to Christianity whereby, through the outer Christ in the soul, the inner Christ, Who is symbolised by the Dove, was awakened to life.

The whole development of the European Mysteries is expressed in yet another cycle of legends and sagas, but it is difficult to speak of them now. We must wait for another occasion.

[Flor and Blancheflor]

Today we will consider how this knowledge found its way into the outer world and made its appearance in a remarkable body of legends. Comparatively little notice has been taken of a legend which was given poetic form by Conrad Fleck in 1230. It is one of the legends of Provence and deals with the Initiation of the Knights of the Grail or the Templars. It speaks of an ancient pair, Flor and Blancheflor. In modern parlance: the flower with red petals (the rose) and the flower with white petals (the lily).

In earlier times it was known that a great many mysteries were contained in this legend ... . It was said: Flor and Blancheflor are souls incarnated in human beings who have lived on Earth. According to the legend, these two were the grandparents of Charles the Great. But those who studied the legend more deeply, saw in Charles the Great the figure who, in a certain sense, united esoteric and exoteric Christianity. This is expressed in the coronation of the Emperor. But in the grandparents of Charles the Great, Flor and Blancheflor, lived the rose and the lily — typifying souls who were to preserve in its purity the esoteric Christianity which had been taught by Dionysos the Areopagite and others.

- The rose — Flor or Flos — symbolised the human soul who has received the impulse of the I, of personality, who lets the Spiritual work out of his individuality, who has brought the I-force down into the red blood.

- But the lily was the symbol of the soul who can only remain spiritual when the I remains outside.

Thus there is a contrast between the rose and the lily. The principle of self-consciousness has entered wholly into the rose, whereas it remains outside the lily. But there was a union between the soul that is within and the soul that as the World-Spirit pervades the universe outside.

Flor and Blancheflor symbolise the finding of the World-Soul, the World-I, by the human soul or the human I.

The event recorded in the legend of the Holy Grail is also described in the legend of Flor and Blancheflor. Flor and Blancheflor must not be thought of as outer figures — the lily symbolises the soul which finds its higher I-hood. The union of the lily-soul with the rose-soul was taken to express that principle in Man which can link him with the Mystery of Golgotha. Therefore it was said: Over against the forces of European Initiation inaugurated by Charles the Great which were to fuse exoteric and esoteric Christianity, pure esoteric Christianity must be kept alive and continued.

[Christian Rosenkreutz]

But among the Initiates it was said: The same soul who lived in Flos or Flor and of whom the legend tells, was reincarnated in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries as the founder of Rosicrucianism, a Mystery-School having as its aim the cultivation of an understanding of the Christ Mystery in a way suited to the new era. Thus esoteric Christianity found refuge in Rosicrucianism.

Since the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries the Rosicrucian Schools have trained the Initiates who are the successors of the ancient European Mysteries and of the School of the Holy Grail.

1909-06-24-GA112

.. [those] whose task it was to carry on the wisdom of all ages, even into our time, were bent upon showing how the higher I of Mankind, the divine spirit of humanity, born in Jesus of Nazareth through the events in Palestine, has remained one and the same, having been truly preserved by those who rightly understood it. And as in the case described above, of the Man whose higher I is born in his fortieth year, the Evangelists described the God in Man up to and including the events in Palestine. The successors of the Evangelists, however, had to show that the events thus described covered the birth of the higher I and that thenceforward we are concerned with the spiritual aspect alone, which now outshines everything else.

The Christians of St. John, whose symbol was the Rosy Cross, said: Precisely that which was reborn as the mystery of humanity's higher self, this same has been preserved intact. It was preserved by that exclusive community which took its rise in Rosicrucianism.

This continuity is indicated symbolically in the legend of the sacred vessel called the ‘Holy Grail’, from which Christ Jesus ate and drank and in which the blood which flowed from His wounds was gathered by Joseph of Arimathea. This vessel, they say, was brought to Europe by angels. A temple was built for it and the Rosicrucians became the guardians of its content, that is, of that which constituted the very essence of the reborn God. The mystery of the reborn God prevailed among men — the mystery of the Holy Grail.

It is presented to us as a new Gospel, and we are told the writer of the Gospel of St. John, whom we venerate, could say in his wisdom: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was a God.’ The same that was in the beginning with God has been born again in Him whom we saw suffer and die upon Golgotha and who is risen again. The continuity of the divine principle through all ages and the resurrection of the same is described by the writer of the Gospel of St. John. But the narrators of such things knew that that which was from the beginning has been preserved unchanged.

In the beginning was the mystery of the higher human I

The same was preserved in the Grail and remained united therewith.

In the Grail lives the I which is united with the eternal and the immortal, even as the lower I is united with the transitory and the mortal

Whoever knows the mystery of the Holy Grail knows that from the wood of the Cross springs living, budding life, the immortal self symbolized by the roses on the dark wood of the Cross. Thus the mystery of the Rosy Cross may be regarded as a continuation of the Gospel of St. John and, in this respect, we may truly speak the following words:

‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was a God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by Him and without Him was no thing made. In Him was the Life and the Life was the Light of men. And the Light shone in the darkness and the darkness comprehended it not. Only a few, in whom something lived that was not born of the flesh, comprehended the Light that shone in the Darkness. Then the Light became flesh and dwelt among men in the likeness of Jesus of Nazareth.’

Now we might continue: ‘And in Christ who dwelt in Jesus of Nazareth we see none but the higher, divine self of all mankind, the God who came down to earth in Adam and was born again. This reborn human self was continued as a sacred mystery; it was preserved under the symbol of the Rosy Cross and is annunciated today as the mystery of the Holy Grail and the Rosy Cross.’

The higher I which may be born in every human soul points to the rebirth of the divine I in the evolution of humanity through the event in Palestine. Even as the higher self is born in every human being, the higher self of the totality of mankind was born in Palestine. The same is preserved and further developed behind the external symbol of the Rosy Cross. But when we consider human evolution, this one great event, the rebirth of the higher I, does not stand alone; beside it there are a number of lesser events.

Before the soul can rise to this all-embracing, all-pervading experience (the birth of the immortal within the mortal self), certain preliminary stages, of comprehensive nature, must be traversed. A man must prepare himself in many and manifold ways. And after this great experience which enables him to say: ‘I now feel something within me, I am aware of something in me that looks down upon my ordinary self, even as my ordinary self looks down upon the objects of sense; I am a second self within the first; I have now risen to the regions in which I am united with divine beings’ - even after this experience there are other different, and still higher stages which must be traversed.

Thus we have the birth of the higher self in every individual Man, and a similar birth for humanity as a whole, the rebirth of the divine I. Then there are preparatory stages and others which succeed this event.

1909-08-23-GA113

regarding the stone from Lucifer's crown

A wonderfully beautiful legend tells us that when Lucifer fell from heaven to earth a precious stone fell from his crown.

This precious stone—so the legend proceeds—became the vessel from which Christ Jesus took the holy Supper with His disciples; the same vessel received the Christ's blood when it flowed on the Cross, and was brought by angels to the western world, where it is received by those who wish to come to a true understanding of the Christ principle.

Out of the stone, which fell from Lucifer's crown, was made the Holy Grail.

This precious stone is in a certain respect nothing else—I will just mention it here, as the fact will be laid more plainly before your souls in the course of the next chapters—than the full power of the I. In darkness this human I had to be prepared for a new and more intelligent beholding if the radiance of Lucifer's star. This I had to school itself by means of the Christ principle, it had to ripen by the aid of the stone fallen from Lucifer's crown, that is to say through anthroposophical wisdom, in order to become capable once more of bearing the light which comes not from without. This light, which only shines in us when we ourselves have the power to do what is requisite for acquiring it, must shine again in the world. Thus people who look at the future with full understanding know that anthroposophical work is work on the human I, which will make it into a vessel capable of again receiving the light which lives in a region where today our sight and intellect apprehend merely darkness and night.

An old legend tells us that night was the original ruler. This night, however, is what today is filled with darkness. But if we permeate ourselves with the light which rises for us when we understand the light-bearer, the other spirit Lucifer, then will our night be turned into day. Our eyes cannot see if the outer light does not illuminate the objects round us; our intellect fails if asked to penetrate beyond the outer nature of things. The star of Lucifer, however, which comes to us when clairvoyant investigation speaks, throws its light on what only seems to be night and changes it into day. And this also takes from us all deadening and paralysing doubt. Then we understand the cross of the Christ in the star of Lucifer. It may be said to be the mission of anthroposophical spiritual life for the future to give us on the one hand certainty and strength whereby, firmly rooted in spiritual life, we may become recipients of the light of the Light-bearer, and on the other hand to make us lean firmly on the rock of unquestioning conviction that nothing which is due to happen through the interaction of forces which are in the world shall fail to happen. Only through this two-fold certainty shall we be able to accomplish what we have to do in the world; only through this two-fold certainty shall we succeed in transplanting anthroposophy into life.

Therefore we must clearly recognise that we have not only the task of understanding the star of Lucifer, as it shone throughout human evolution till the precious stone fell out of Lucifer's crown, but that we have to receive this precious stone in its transformed character as the Holy Grail, that we must understand the Cross in the star; we must know that we have to understand the luminous wisdom which shone in the world during primeval ages, and which we deeply revere as the wisdom of pre-Christian times.

To this we must indeed look up in full devotion, and add to it that which could be given to the world through the mission of the Cross. Not the least fraction of pre-Christian wisdom, of the light of the East, must be lost to us. We look up to phosphoros, the Light-bearer; and indeed we revere this Light-bearer as the being through which alone we learn to understand the whole of the deep, inner meaning of the Christ; but side by side with Phosphoros we see Christophoros, the Christ-bearer, and we try to conceive of the mission of anthroposophy in such a way that it only can be fulfilled if the symbols of these two worlds really ‘unite themselves in love.’ If this is our conception of the mission of anthroposophy, Lucifer will guide us to the safety of a luminous spiritual life, and the Christ will guide us to the inner warmth of the soul which trusts and believes that that will come about which may be called the birth of the Eternal out of the Temporal.

[2.1] - Storyline and characters

Lohengrin

1905-03-28-GA092

is on Wagner's Lohengrin opera

The Swan-Knight therefore appears to us as an emissary of the great White Brotherhood. Thus Lohengrin is the messenger of the Holy Grail. A new impulse, a new influence was destined to enter human civilisation. You already know that in mysticism the human soul, or human consciousness, always appears as a woman. Also in this legend of Lohengrin the new form of consciousness, the civilisation of the middle classes, the progress made by the human soul, appears in the vestige of a woman. The new civilisation which had arisen was looked upon as a new and higher stage of consciousness. Elsa of Brabant personifies the medieval soul. Lohengrin, the great initiate, the Swan of the third degree of discipleship, brings with him a new civilisation inspired by the community of the Holy Grail.

He must not be asked any questions, for it is a profanation and a misunderstanding to place questions to an initiate concerning things which must remain occult.

The influence of great initiates always brings about the promotion to new stages of consciousness. ...

.. also in the legend of Lohengrin we come across such a moment of initiation. These legends are important indications, which can only be understood by those who possess an Insight into the connections of things.

The Lohengrin legend (as explained, it is connected with the legend of the meister-singers) has a decidedly Catholic character. Richard Wagner used it for his Lohengrin poem. This reveals Richard Wagner's high inner calling.

1905-10-04-GA093a

The 14th century was the time of the creation of towns. Within a few hundred years independent towns had developed in all civilised European countries. The burgher is the founder of materialism in practical life. This comes to expression in the Lohengrin myth. Lohengrin, the emissary of the Grail Lodge, was the wise leader who took hold in the Middle Ages and prepared the way for the establishment of towns. The swan was his symbol; the initiate of the Third Grade is the Swan. Consciousness is always represented as something feminine. Elsa of Brabant represents the consciousness of the materialistic civic sense.

1905-12-03-GA092

Kundry the tempress of the lower nature

1906-07-29-GA097

The Templars were those who stood for true Christianity as distinguished from Church Christianity. In the Middle Ages remnants were still left of the old degenerate mysteries. All that belongs to those is grouped together under the name of Klingsor. He is the black magician in contrast to the white magic of the Holy Grail. Wagner places him in opposition to the Templars.

Kundry is the modern version of Herodias, the symbol of the force of reproduction in nature, the force that can be chaste or unchaste, but is uncontrolled. Beneath chastity and unchastity lies a fundamental unity; everything depends on the way of approach. The force of reproduction that shows itself in the plants, within the chalice of the blossom, and right up through the other kingdoms of nature, is the same as in the Holy Grail. Only, it has to undergo purification in that noblest and purest form of Christianity which manifests in Parsifal.

Kundry has to remain a black enchantress until Parsifal releases and redeems her. In the polarity of Parsifal and Kundry we can sense the working of deepest wisdom. Wagner, more than anyone else, took care that men should be able to receive what he had to give without knowing that they were doing so. He was a missionary who had a most significant message to deliver — to deliver, however, in such a way that mankind was not aware of receiving it.

1905-05-19-GA092

On the one side, we have the temple of the Holy Grail with its knights, and on the other, the Magic Castle of Klingsor with his knights, who are, in reality, the enemies of the knighthood of the Holy Grail. We are confronted with two forms of Christianity. One kind is represented by the knights of the Holy Grail and the other by Klingsor. Klingsor is the man who has mutilated himself in order not to fall a prey to the senses. But he has not overcome his desires, he has only taken away the possibility to satisfy them. Thus he lives in a sensual sphere. The maidens of the magic castle serve him, and everything belonging to the sphere of desires is at his disposal.

Kundry is the real temptress in this kingdom: she attracts everyone who approaches Klingsor into the sphere of sensual love. Klingsor has not destroyed desire, but only the organ of desire. He personifies the form of Christianity which comes from the South and introduced an ascetic life; it eliminated a sensual life, but it could not destroy desire; it could protect against the tempting powers of Kundry. A higher element was perceived in the power of a spirituality which rises above sensual life into the sphere of purified love, not through compulsion, but through a higher, spiritual knowledge.

Amfortas and the knights of the Holy Grail strive after this, but they do not succeed in establishing this kingdom So long as the true spiritual force is lacking, Amfortas yields to the temptations of Kundry. The higher spirituality personified in Amfortas falls a prey to the lower memory.

[2.5] - Symbols and challenges

1913-03-25-GA145

(SWCC) - see Ganganda greida for full extract

Symbolised by the brain lying within the skull, our human nature on the earth appears as a being under enchantment living in a castle, as a being imprisoned and enclosed by stone walls. Our skull is like the shrunken external symbol of this. But when we look at the etheric forces which lie at its foundation, the earthly man actually appears to us as if he were within the skull, and imprisoned in this castle.

And then from the other parts of the organism there stream up the forces which support this human being who is really within the skull as if in a mighty castle; the forces stream upwards;

- first the force which comes from the outspread instrument of the astral body: all streams up all that strengthens Man's nerve fibres. All this streams together in the earthly brain-man; this appears as a mighty sword which the human being has forged on the earth.

- Then stream up the forces of the blood. These appear as that which really wounds the brain-man lying in the enchanted castle of the skull. The forces which in the etheric body stream up to the earthly human being lying in the enchanted castle of the brain are like the bloody lance, streaming up to the noblest parts of the brain.

...

The I and astral body — the spiritual man — descends into the castle, which is formed of that which is only seen symbolically in the skull. Here the human being lies sleeping, wounded by the blood, the Man of whom we see that thoughts are his strength — that which must be capable of nourishment by all that comes from the kingdom of nature, that which in its purest parts must be served by the finest.

All this symbolically represented resulted in the Legend of the Holy Grail, which tells us of that miraculous food which is prepared from the finest activities of the sense impressions and the finest activities of the mineral extracts, whose purpose it is to nourish the noblest part of man all through the life he spends on earth; for it would be killed by anything else. This heavenly food is what is contained in the Holy Grail.

And that which otherwise takes place, that which presses up from the other kingdoms, we find clearly represented if we go back to the original Grail legend, where a meal is described at which a hind is first set on the table. The penetrating up into the brain where for ever floats the Grail, that is, the vessel for the purest food of the human hero who lies in the castle of the brain, and who is killed by everything else ..

Manly P. Hall

In the great temple on Mount Salvat stands Parsifal, the third and last king of the Holy Grail, holding aloft the scintillating green Grain Cup and the sacred spear.

…

The key to the Grail Mysteries will be apparent if

- in the sacred spear is recognized the pineal gland with its peculiar pointlike projection

- and in the Holy Grail the pituitary body containing the mysterious Water of Life.

Mount Salvat is the human body; the domed temple upon its summit, the brain; and the castle of Klingsor in the dark valley below, the animal nature which lures the knights (brain energies) into the garden of illusion and perversion.

The name of the Grail in the stellar script

1914-01-02-GA149

see Schema FMC00.116 above

[2.5] - Grail literature and versions

Rudolf Steiner as of 1904-5 usually referenced Wolfram von Eschenbach version of the Grail story, however he referenced de Troyes version too, and also comments on the famous Kyot mentioned by von Eschenbach.

Rudolf Steiner calls Wolfram von Eschenbach an initiate (1904-07-15-GA092) and describes he was inspirated (1904-07-01-GA092)

Wolfram von Eschenbach wrote his Parzifal as a plain and simple epic. That was sufficient in his day. People who had some degree of clairvoyance at that time understood Wolfram von Eschenbach

1904-07-15-GA092

(freely translated)

1913-03-25-GA145

The best presentation of this is not that by Wolfram, but it is best represented in an external exoteric way (because almost everyone can recognise, when his attention has been drawn to it, that this legend of the Grail is an occult experience which every human being can experience anew every night), it is best represented, in spite of the profanation which has even crept in there, by Chrestien de Troyes. He put what he wished to say in an exoteric form, but this exoteric form hinted at what he wished to convey, for he refers to his teacher and friend who lived in Alsace, who gave him the esoteric knowledge which he put into exoteric form. This took place in an age when it was necessary to do this, on account of the transition indicated in my book, ‘The Spiritual Guidance of Humanity.’ The Grail legend was made exoteric in 1180, shortly before the transition.

1914-01-01-GA149

On other occasions I have mentioned that the best literary account of Parsifal's arrival at the Castle is to be found in Chrestien de Troyes.

and regarding Steiner's research into exoteric sources

And now, as my concern was to find the Vessel, I was at first misled by a certain circumstance. In occult research — I say this in all humility, with no wish to make an arrogant claim — it has always seemed to me necessary, when a serious problem is involved, to take account not only of what is given directly from occult sources, but also of what external research has brought to light. And in following up a problem it seems to me specially good to make a really conscientious study of what external scholarship has to say, so that one keeps one's feet on the Earth and does not get lost in cloud-cuckoo-land.

But in the present instance it was exoteric scholarship (this was some time ago) that led me astray. For I gathered from it that:

.. when Wolfram von Eschenbach began to write his Parsifal poem, he had — according to his own statement — made use of Chrestien de Troyes and of a certain Kyot. External research has never been able to trace this Kyot and regards him as having been invented by Wolfram von Eschenbach, as though Wolfram von Eschenbach had wanted to attribute to a further source his own extensive additions to Chrestien de Troyes. Exoteric learning is prepared to admit, at most, that Kyot was a copyist of the works of Chrestien de Troyes, and that Wolfram von Eschenbach had put the whole thing together in a rather fanciful way. So you see in what direction external research goes. It is bound to draw one away, more or less, from the path that leads to Kyot.

At the same time, when I had been to a certain extent led astray by external research, something else was borne in upon me (this was another of the karmic readings). I have often spoken of it — in my book Occult Science and in lecture-courses — and should now like to put it as follows.

...

Then I tried once more to get back to Kyot, and behold — a particular thing said about him by Wolfram von Eschenbach made a deep impression on me and I felt I had to relate it to the ‘ganganda greida’. The connection seemed inevitable.

I had to relate it also to the image of the woman holding her dead bridegroom on her lap. And then, when I was not in the least looking for it, I came upon a saying by Kyot: “er jach, ez hiez ein dinc der gral” — “he said, a thing was called the Grail.”

Now exoteric research itself tells us how Kyot came to these words: “er jach, ez hiez ein dinc der gral.” He acquired a book by Flegetanis in Spain, an astrological book. No doubt about it, one may say: Kyot is the man who, stimulated by Flegetanis (whom he calls Flegetanis and in whom lives a certain knowledge of the stellar script), Kyot is the man who, stimulated by this revived astrology, sees the thing called the Grail. Then I knew that Kyot is not to be given up; I knew that he discloses an important clue if one is searching in the sense of Spiritual Science: he at least has seen the Grail.

1914-01-02-GA149

quote about Prester John

Anyone who wishes to hold fast to a narrow creed will certainly not be immediately convinced by what has been said. This is because he pays heed to the superficial course of events, and so to the external aspect of the real deeds of Christ, which are themselves of a spiritual nature. How a man was led by his karma to the spiritual deeds of Christ; how Parsifal was driven along this path, wherein is prefigured the unity of religions on Earth—that is what we have wished to bring before our souls.

And we should keep in mind that continuation of the Parsifal saga which says that when the Grail became invisible in Europe, it was carried to the realm of Prester John, who had his kingdom on the far side of the lands reached by the Crusaders.

In the time of the Crusades the kingdom of Prester John, the successor of Parsifal, was still honoured, and from the way in which a search was made for it we must say: If all this were expressed in terms of strict earthly geography, it would show that the place of Prester John is not to be found on Earth.

Discussion

Note 1 - The various English versions of Von Eschenbach's in English

Review by Ian Myles Slater, taken from amazon

Added here with respect for source as valuable information for interested readers, with additional info of value given too (SWCC):

When I reviewed two translations of Wolfram von Eschenbach's "Parzival" in January 2005, there were three complete English translations available of the Middle High German poem, an early, and slightly eccentric, version of the Grail Quest, composed between about 1200 and 1210 by a knight and (slightly eccentric) poet from southern Germany.

All three translations were in prose, unlike Jessie L. Weston's two-volume pioneering, and then-out-of-print (I think), "Parzival: A Knightly Epic," originally published in 1894, and the primary subject of the present review. Jessie L. Weston was an industrious translator of medieval Arthurian (and some other medieval) literature, and a lot of her out-of-copyright books have been picked up and re-issued. She was also a Wagner enthusiast (her "Parzival" is dedicated to him). The most famous of her books is "From Ritual to Romance," a highly-speculative, but fascinating, study of the Holy Grail traditions, which she tried to connect to a variety of religious traditions; this is available in a number of formats (although it has been a good many years since Arthurian scholars took her thesis seriously). Her views on the Grail story in any case are based on the French versions of the story, and do not directly involve Wolfram's decidedly atypical treatment of the subject.

I will deal with the more modern competition first. It should be made clear that I think these later translations are more readable, although the three (at the moment) Kindle editions of Weston's translation are less expensive than either of the Kindle (or paperback) editions of two of the three two prose translations. I will include as well some general observations on Wolfram and his major works, before returning to Weston's version.

- The first of the prose translations was Helen M. Mustard and Charles E. Passage's Vintage paperback (Random House, 1961), Parzival: A Romance of the Middle Ages," which is (apparently) now out of print.

- It was followed a couple of decades later by A. T. Hatto's "Parzival" (A Penguin Classic, 1980).

- The third was "Parzival: With Titurel and the Love Lyrics," translated by Cyril Edwards ("Arthurian Studies" series, D.S. Brewer, 2004). In 2006, Edwards' volume was reduced in scope to "Parzival and Titurel" as an Oxford World's Classics paperback, which also omitted the original introduction, and some technical apparatus. Some of us miss having them. It now has a competent and readable new introduction by Richard Barber, focusing on the Arthurian context, which is relatively well-known, and less about thirteenth-century German literature. The narratives, however, are complete. Thanks to Edward's decision to reproduce Wolfram's stylistic oddities as much as possible, his translation is less welcoming than the two earlier prose translations, but also more intriguing for those who are willing to take it slowly. Thanks to the difference in title, its reviews have not been lumped together with other translations, as befell the Mustard-Passage and Hatto translations -- which is why I initially reviewed those two together, and constantly compared them.

Both Edwards' "Parzival and Titurel" and Hatto's "Parzival" are now available in Kindle formats. When I eventually reviewed Edwards' translation, I did so from the Kindle edition, without immediate reference to the full-length library copy in which I first encountered it several years before. {NB 2021: The Edwards translation is no longer available in Kindle. I am not certain how long this has been the case.}Those interested in trying Jessie Weston's nineteenth-century rendering can sample her verse style by using the "Look Inside" or "Sample" functions of the Kindle editions. Some readers may enjoy it (I don't). It should be pointed out that the nineteenth-century edition of this Middle High German text from which she worked is quite obsolete, as is the translation into modern German (by Simrock) to which she also referred.

Beside "Parzival," a long Arthurian (and Grail) romance, and the fragments of "Titurel," which picks up stories and characters from "Parzival," Wolfram composed a long Carolingian epic, "Willehalm," based on a French chanson de geste, and some charming lyrics.

Wolfram's complaints about rival poets, and their complaints about him, have turned out to be clues to relative dating of their works. From this, and some external evidence, Wolfram's poetic career has been dated between about 1195 and 1225; with the almost 25,000 lines of "Parzival" being composed between about 1200 and 1210.

Wolfram seems to have had the last laugh on his critics; "Parzival" apparently was far-and-away the most popular German work of the thirteenth through the fifteenth centuries, with something like ninety known manuscripts, and a 1477 print edition. Perhaps inevitably, the fragments of "Titurel" were "completed" in another long romance, long thought to be Wolfram's own work, but now called the "Juengere" (Follower's) "Titurel."

In "Parzival," Wolfram himself was translating, in his own wayward fashion, Chretien de Troyes' unfinished "Perceval, or, The Story of the Grail" -- although he himself claims to have an additional source, the mysterious "Kyot," who had a better, truer, version. Since Chretien himself claimed to have been working from a source provided by a patron, this has at times sent scholars searching in many directions. In his introduction to the Oxford World Classics volume, Richard Barber argues that the "better source" was entirely a creation of Wolfram's fertile imagination, and scraps of irrelevant but interesting ideas. He is probably right about the back-story Wolfram creates for it.

A Preface introduces the reader (or listener) to Wolfram's moral concerns, and also to his sometimes-maddening use of riddles and metaphors. We then have an entire opening section with the hero's father, Gahmuret the Anschevin [i.e., Angevin], having adventures in a vaguely-conceived Near East and North Africa, where he leaves a "pagan" wife and son: the latter, the multi-colored Feirefiz, crosses paths with his younger brother, the main hero, years later. (It is worth noting that, although Wolfram is a snob, and is fascinated by physical differences between human beings, he is in no sense a racist; color is no bar to aristocracy.)

(To me, it looks very much as if Wolfram had some sort of additional material -- there are odd resemblances to "Morien," an apparent interpolation in the medieval Dutch translation of the Lancelot-Grail romances, featuring Perceval's "Moorish" nephew -- but to have used his imagination quite freely in accounting for it. A prose translation of "The Romance of Morien" by Jessie Weston is available in various Kindle editions, one rather randomly illustrated from medieval manuscripts, and as an on-line PDF -- see Weston's Wikipedia biography for a link.)

Gahmuret's story is somewhat filled out in the first fragment of "Titurel," but why Wolfram made him an Angevin is unclear; it perhaps has something to do with the accession of a Count of Anjou's son to the throne of England (Henry II), but so far more detailed explanations -- including those by Jessie Weston -- have trailed off into unprovable speculation. (In England, the family became better known as the Plantagenets.)

This material is followed by Gahmuret's second marriage, and death, and, joining up with Chretien's narrative, the birth and upbringing in forest isolation of Parzival himself (the idea being to keep him from dying in battle like his father). There follows the ignorant boy's fateful encounter with some of Arthur's knights, his attempts at chivalry, and the splitting of the story to include the exploits of Sir Gawain (recognizable under German renderings, variously handled by translators over the years), and Parzival's first adventure at the Grail Castle. Although this is derived from Chretien's account of Perceval and "Messire Gauvain, " it is retold in Wolfram's quirky style, instead of an imitation of Chretien's famously lucid Old French verses. (Eric Rohmer's film version of "Perceval" is a splendid visualization of Chretien's version, and works almost equally well for the relevant parts of Wolfram's retelling, too.)

In both Chretien's and Wolfram's versions, there is a lot of comedy derived from the boy's literal-mindedness and ignorance of the world, and the resulting blunders, contrasted with his great strength and physical beauty. (He bears some resemblance to the original, animated, version of "George of the Jungle," except for the smashing headlong into trees.)

Then Wolfram returns to what seems to be new material, writing his own conclusion, including the maturation of Parzival. This also seems to have been in Chretien's mind, but he left this romance, as well as his "Lancelot," unfinished.

As in other versions, including the Old French "Continuations" of "Perceval," and the prose "Perlesvaus" (or "High History of the Holy Grail"), Wolfram draws Chretien's very mysterious "graal" into a Christian conception of the universe. But Wolfram explains it as a sort of magic stone that fell to earth during the War in Heaven, not a relic of the Last Supper. That more explicitly Christianized version seems to belong to the Old French cycle of "Joseph of Arimathea," "Merlin" and "Perceval," attributed to Robert de Boron, and was later picked up and amplified in the "Vulgate Cycle" of Arthurian romances (centering on Lancelot, and introducing Galahad as the Quest hero, alongside Perceval), the version known in English through Malory, and, so far as the Chalice interpretation, also used by Wagner.

Wagner plundered Wolfram for names and a certain "German" quality for his Grail opera, "Parsifal," besides using another version of a story Wolfram alludes to in "Lohengrin,' and the poet's name for a character in "Tannhauser." Personally, I suggest tossing aside all Wagnerian preconceptions, if any, and allowing Wolfram's real personality to have a chance. Sarcastic (especially about competitors), sentimental (especially about wives and children), full of pride in the knightly caste (a new phenomenon, which its members wanted to be very old), arrogantly announcing that he is completely illiterate in the company of poets who boasted they could read anything ever written, he is both annoying and lovable. A living personality, in fact, appearing in a time used to anonymous authors.

For those who find "Parzival" a pleasure, or who would like to try a more military, rather than chivalric, work, there are also translations of his "Willehalm," based on the Old French *chanson de geste* of William Curt-Nose, or Guillaume l'Orange, one of the heroes of the legends of Charlemagne and his descendants. I am familiar with two, both into prose. One, by Marion E. Gibbs and Sidney M. Johnson, was published by Penguin Classics in 1984, and is currently in print, as "Wolfram von Eschenbach: Willehalm." Charles E. Passage, one of the co-translators of "Parzival," had earlier translated it as "The Middle High German Poem of Willehalm by Wolfram von Eschenbach," published by Frederick Ungar in 1977. Although it is out of print, used copies of the trade paperback edition seem to be available. (Passage also translated "Titurel" for Ungar (1985), which, unfortunately, I haven't seen.)

Curiously, the supposedly illiterate Wolfram seems unusually aware of the idea (if not the facts) of history. The "Pagan" Saracens of his French source are connected by him with the Romans (as descended from the followers of Pompey, rather than of Caesar, and heirs of an old feud), and also with the extra-European characters he had already invented for "Parzival." He rather neatly brings into the correct sequence his versions of Arthurian and Carolingian Europe.

The main problem I see with Weston's translation of Wolfram is its use of rhymed couplets, which many readers may find wearying long before the end of the second volume. (There is also the distortion of meaning to fit meter and rhyme to worry those especially concerned to get at Wolfram's precise meaning.) Her appendices look helpful, but are as obsolete as the nineteenth-century scholarship from which they are derived.

Nabu Press has issued in paperback Weston's "Parzival," as well as out-of-copyright German text editions and modern German translations. Many of these, and others, can be also be found at archive.org (the Library of Congress website), although the two volumes of Weston's translation must be searched for as "Parzival," and not under the translator's name. (Archive.org also makes available the 1891 fifth edition of Karl Lachmann's enduring edition of Wolfram's works; Edwards, and, I think, the other modern translators, mainly used the 1926 sixth edition, or the seventh -- the current version, published by De Gruyer, may be the eighth.) There are also Project Gutenberg editions of a number of Weston's works, including "Parzival," some of them available in Kindle format, among other versions.

Manfred Schmidt-Brabant (1997)

see: 'Paths of the Christian Mysteries: From Compostela to the New World' (2003), Lecture4

Schmidt-Brabant suggests the second grail castle may have been San Millan de Susa.

Then the onyx cup leaves for San Jual de la Pena, the Grail goes to Monsegur where the castle was built to protect the Grail (1204); but Montsegur is destroyed as a result of the catastrophe of the Cathars.

Related pages

References and further reading

- Ernst Uehli

- 'Eine neue Gralsuche' (1920 or 1921)

- Zwischen Sphix und Gral

- Walter Johannes Stein:

- 'The ninth century and the holy grail' (1988 in EN, original in DE 1927 or 1928: 'Weltgeschichte im Lichte des heiligen Gral : Das grosse neunte Jahrhundert')

- Gralsgeschichte (typoscript)

- Sigismund von Gleich: 'De heilige graal en de nieuwe tijd van Christus' (1952, in NL 1986)

- Julius Evola: 'Das Mysterium des Grals' (1955)

- Rudolf Meyer:

- 'Der Gral und seine Hüter' (1956, 3th edition 1980, 6th edition 2003)

- also published from 1980 as 'Zum Raum wird hier die Zeit : die Gralgeschichte'

- Fred Poeppig: 'Wege zum heiligen Gral : in ihrer Bedeutung für das meditative Leben des modernen Menschen : Iona' (1959)

- Heinrich Teutschmann: 'Siebenhundert Jahre Gralsdichtung : der Gral im Wort seiner Dichter' (1968)

- Karl Koenig: 'The Grail and the the development of conscience - St Paul and Parsifal'

- Johanna von Keyserlingk: 'Gralburg' (Vol 1 & 2) (1968)