Christ Module 13 – Teachings through the ages

This Module is about the teachings about Christ and the Christ Impulse through the ages, with different names and languages in the various cultures.

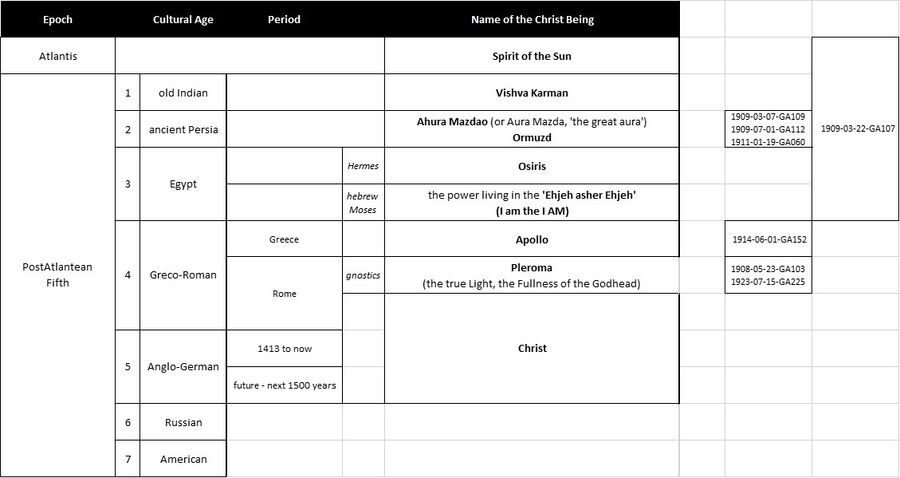

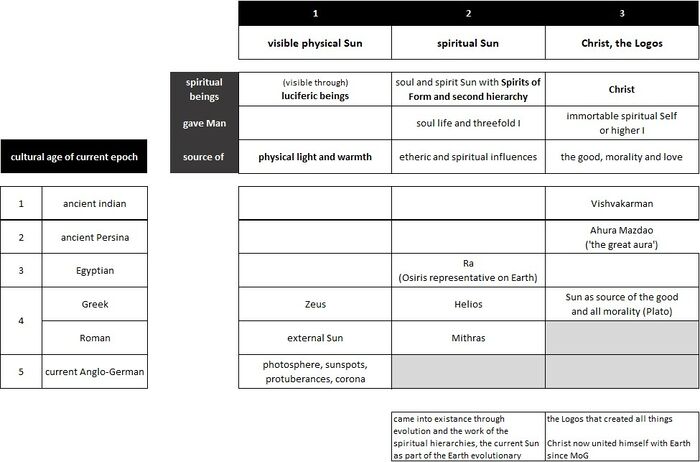

Schema FMC00.090 below provides an overview of the various names in different epochs and cultural ages.

Atlantean epoch

- Sun Mysteries on Atlantis: the Spirit of the Sun

Current Postatlantean epoch

Northern stream

Southern stream

- ancient Indian cultural age

- Seven Rishis: Vishva Karman

- ancient Persian age

- Zarathustra: Ahura Mazdao and Ormuzd

- Egypto-Chaldean cultural age incl. Hebrew

- Osiris (Isis and Horus) and Ra

- Hebrew: Ehjeh asher Ehjeh (I am the I AM), the five books of Moses, see Book of Genesis

- Greco-Latin cultural age

- Greece

- Apollo, Zeus and Helios

- Roman age

- Mithras

- the four gospels: four perspectives, their meaning and complementarity (see also Gospel of John as an initiation document)

- the school of Paul (and Dionysus), and the school of John (see also Book of Revelation)

- the gnostics: see Gnosis and gnostic teachings

- Pleroma see also Evolution Module 2 - Earth#1908-09-03-GA106

- Greece

Merged streams

- Current fifth Anglo-German cultural age

- theosophy and anthroposophy - spiritual scientific perspective on all previous teachings incl. the gospels

- fifth gospel

Aspects

christianity as a religion

- religion is a connection of the sensual with the supersensible (latin 'religere' means 'to connect') .. in earlier times of natural clairvoyance humanity did not need a religion, but as the vision of the spiritual world faded into times of rising materialism, mankind needed religion. The time will come when people will be able to have experiences in the supersensible world again, and then they will no longer need religion. (1908-05-13-GA102). As humanity advances ever more to super-sensible knowledge, there will be an ever deeper comprehension of the Mystery of Golgotha, and with it of the Christ Being. (1922-04-13-GA211)

- after the advent of Christ-Jesus and the Mystery of Golgotha, no new religion can be founded (1922-04-13-GA211)

- Christianity began as a religion but is greater than all religions (1908-05-13-GA102)

- earlier epochs like in the Atlantean epoch did not need a religion because Man's clairvoyant experience of the supersensible was a fact. The latin 'religere' means to connect, and so religion is a connection of the sensual with the supersensible. The time of the rising materialism needed religion.

- in the future people will again have experiences in the supersensible and higher spiritual worlds, then they will no longer need religion. Even when people have overcome religious life, Christianity will remain and human beings shall be bearers of spiritual Christianity.

- "Christianity as a world view is greater than all religions": the future new clairvoyant vision will bring along spiritual Christianity .. Christianity will remain even when religion (as connected with the evolutionary process of humanity) has been transcended. (1908-05-13-GA102)

the spreading of Christianity

- Roman empire

- the roman emperors ... "because of their forced initiation which gave insight into the spiritual world, had a presentiment of the far-reaching importance of the Christ Impulse ... some of the more talented and perspicacious emperors began to pursue a definite policy towards Christianity ... the first emperor to adopt this policy was Tiberius (AD 14 until 37) who succeeded Augustus ... when he learned of Christ's birth in Palestine, Tiberius—who had received a partial initiation into the ancient Mysteries, realized its significance ... that policy towards Christianity which began under Tiberius ... who announced his intention to admit Christ to the Roman pantheon. " (1917-04-17-GA175)

- see also extensive coverage on: Mystery School tradition#Note 1 - Regarding the timing of the "college for destruction of initiation and spirit"

- furthermore on the Palladium: Threefold Sun#Note 2 - The Palladium as a symbol of the secret of the sun

- Christianization of the people of central Europe, with missionaries as Patrick, Columban, Gallus, Boniface and Ireland as the source of the impulse of true esoteric Christianity

- see coverage on Central European cultural basin.

- Christianity grew into ever new areas and among new tribes through its adaptability and this expanded more and more but in multiple forms. Examples: inclusion of pagan religious form with Christian essence, Mithras festival, Christmas festivals and saints, etc. "From the very beginning, Christianity's task in conquering the physical plane was to work its way into the human personality; it does not build on old forces, but seeks to work through manas or spirit-self." (1904-06-24-GA092; see Reconquista#1904-06-24-GA092)

- until the 7th or 8th century (in a kind of echo of pre-Christian initiation) Christianity was taught in centers that had remained as the high places of knowledge, relics of the ancient Mysteries. In those centers human beings were prepared, not so much by way of instruction, but by an education towards the spirit, a training both bodily and spiritual. (1924-07-13-GA237)

Other

- relativity of the faculty of thinking, information and knowledge for the spreading of the Christ Impulse, on the contrary Christianity spread through 'simple' souls touching the heart of people, facing intellectual resistance and no understanding (1913-10-01-GA148)

- difference between 'organized, human' religion, theology, faith, spiritual science

- belief systems (see worldview) vs experiential (see initiation and initiation exercises, and God experience)

- faith had a different meaning at the time of the Christ and the Gospels as it has today .. then with Faith was meant an active force accomplishes something .. not simply evoke an idea or to awaken knowledge (as is how the word is used today). (1917-04-10-GA175)

- MoG and its impact on conceptions of two key phenomena in the life of mankind: death and heredity (1918-10-06-GA184)

Various more

- See also:

- the Individuality of Christian Rosenkreutz, see also Mystery of John

- The Michaelic stream of souls

- see also related: Threefold Sun

Inspirational quotes

1901-GA008 quotes Augustinus

One of his most significant utterances is the following:

"What is now called the Christian religion already existed among the ancients, and was not lacking at the very beginnings of the human race. When Christ appeared in the flesh, the true religion already in existence received the name of Christian"

(Augustinus, Contra Faustum 33:6)

The clairvoyant Atlantean did not need a religion because the experience of the supersensible was a fact for him. All human development originated in such a time. Then the vision of the spiritual world faded.

Religere means to connect, and so religion is a connection of the sensual with the supersensible. The time of the rising materialism needed religion.

But the time will come when people will be able to have experiences in the supersensible world again. Then they will no longer need religion. The new vision requires the bringing along of spiritual Christianity, it will be the consequence of Christianity. This is the basis for the sentence that I ask you to remember as particularly important: Christianity began as a religion, but it is greater than all religions.

What Christianity has given will be taken along into all times of the future and will still be one of the most important impulses for humanity when religion as such no longer exists. Even when people have overcome religious life, Christianity will remain. That it was first a religion is connected with the development of humanity; but Christianity as a world view is greater than all religions.

also as epilogue in the book 'The Christian Mystery. A collection of early lectures by Rudolf Steiner' titled: "Christianity Began as a Religion but Is Greater than a Religion"

The necessary antecedent of the new vision is that human beings shall be bearers of spiritual Christianity. This is the basis of the sentence of which I would ask you to realize the profound significance: Christianity began as a religion but is greater than all religions.

What Christianity bestows goes with us into all ages of time to come and will still be one of the essential impulses in humanity when religion, as we know it, is no longer in existence. Even when religion, as such, has been transcended, Christianity will remain.

The fact that it was first of all a religion is connected with the evolutionary process of humanity. But Christianity as a world view is greater than all religions.

Illustrations

Historical names of Christ and the Sun God

Schema FMC00.090: lists the different names of Christ used across the cultural ages of the Current Postatlantean epoch. See also Schema FMC00.267.

Notes:

- see also Schema FMC00.481 and the Greek term Christos as it relates to the cosmic principle of buddhi (in theosophy) or life-spirit (in anthroposophy).

- regarding the actual meaning of ‘Jesus' (in earlier ages when names still pointed to certain realities): "in a dialect of Asia Minor, among those associated with the birth of Christianity, the word ‘Jesus’ was the translation of the expression ‘spiritual healer’. Jesus expresses ‘spiritual physician’ and this is a fairly correct interpretation" (1910-09-10-GA123, see Mystery School tradition#1910-09-10-GA123)

- regarding Osiris in teachings from ancient Egypt: one distinguishes between Ra and Osiris: the god Ra, "the rising sun and by the father of heaven and earth" (1902-03-01-GA087) .. "whose representative on Earth was Osiris, the son of the supreme god" and "Man is called to undergo the development that makes him Osiris" (1902-02-22-GA087 and 1922-04-24-GA211, see Threefold Sun#1922-04-24-GA211), "the third part of the Book of the Dead ... shows the path to reach Osiris, the path that leads to deification" (1901-11-30-GA087). With Osiris is meant the human archetype of what would later be lived as Christ-Jesus, and the 'not I but Christ in me' of the Rosicrucians, that is: the future Man-God that becomes part of the Christ as future group soul of humanity, see Second Adam.

Schema FMC00.267 provides a summary table of the Threefold Sun and the various names of Christ - see also Schema FMC00.090.

From Elisabeth Vreede's letter of Dec. 1927.

Old and new wisdom

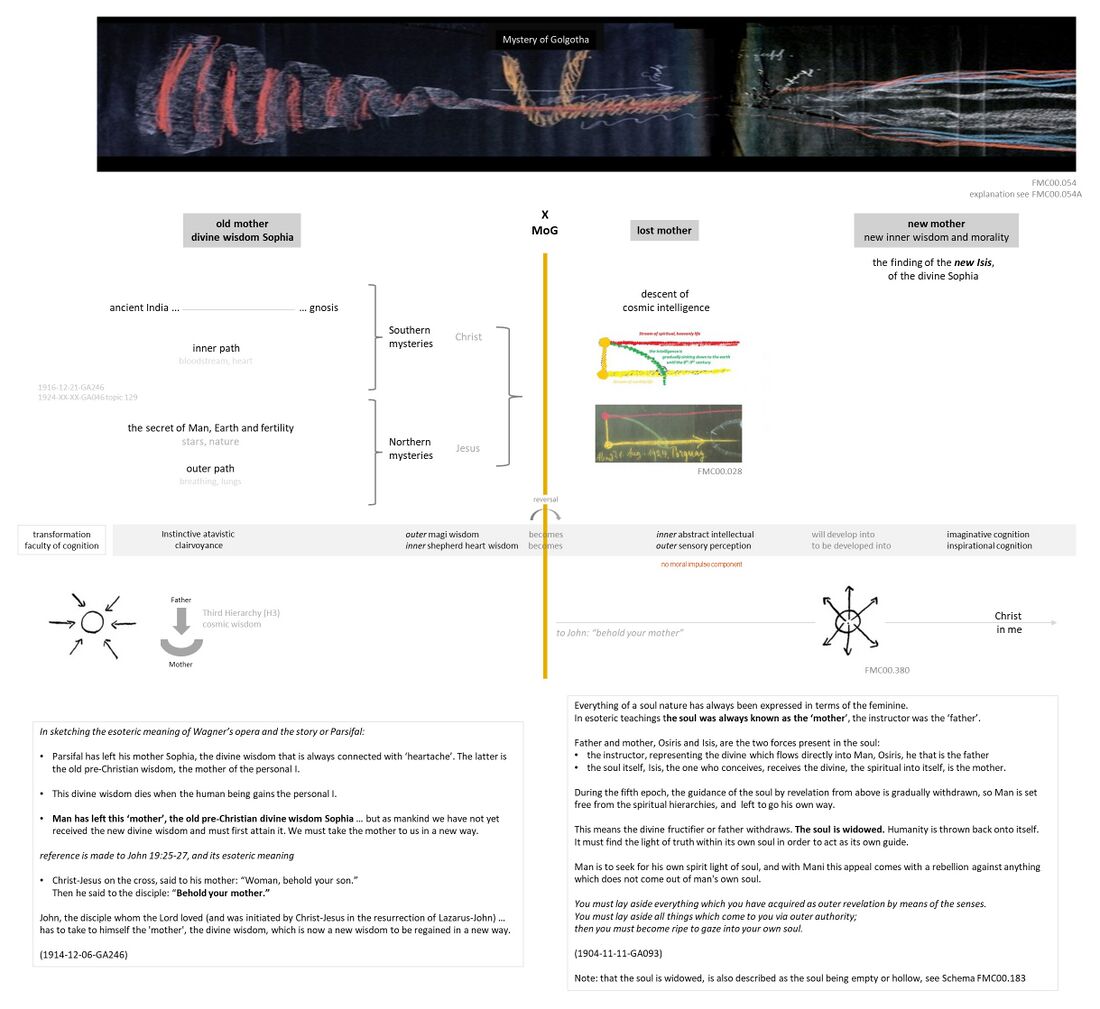

Schema FMC00.694: is a meta study schema that brings together various perspectives (1) to (6) related to the changes in human consciousness and humanity's path from old to new wisdom (or Sophia) before and after the Mystery of Golgotha. The Schema covers a lot of ground, and is an example of how this can be used to structure and guide one's study approach by exploring the perspectives offered through study of the specific schemas and quotes. To approach this, first

below: (1) are two text lecture extracts with as central key the 'mother', as in the phrase 'behold your mother' from John's gospel 19:26-27. These excerpts are deliberately taken from other contexts (left: description of Wagner's Parsifal opera, and right: on Manicheism) to show how consistent the key teachings from spiritual science come back and are covered from various contexts and perspectives.

With 'mother' is meant the divine wisdom called Sophia, when in ancient times human beings had an atavistic clairvoyance inspired by the Third Hierarchy; as depicted by the infographic lower left. Later, through the development of the human 'I' and the 'descent of the cosmic intelligence' into Man (shown in the middle), the spiritual hierarchies withdrew and the human soul was widowed.

The Mystery of Golgotha brought about a 'reversal', from descent to ascent and spiritualization, from blood-based to spiritual love. John has to take to himself (and explain, as the scribe of Christ-Jesus) the 'mother', the new divine wisdom through the MoG, to be regained in a new way. This links to the Gospel of John as an initiation document, and the rosecrucian teachings from the impulse of Christian Rosenkreutz. The old divine wisdom dies when the human being gains the personal I, Man has lost the 'mother' (wisdom in the soul), an emptiness also described on Schema FMC00.183 ... but has not yet received the new divine wisdom and must first attain it. (1914-12-06-GA246).

left: (2) the polarity between the Southern and Northern mysteries describe, on the one hand the southern stream with outer knowledge of the macrocosmos and spiritual beings - the last known version of which was gnosis and gnostic teachings; and on the other hand the northern stream with inner knowledge of Man and the Earth. These perspectives relate to Christ as a spiritual being and Jesus as the human being, but also to different spiritual influences on Man, a polarity described (see below) through magi and shepherds (see Schema FMC00.695)

middle - grey horizontal bar: transformation of faculty of cognition. As context: over the millenia of the dark age or kali yuga the the ancient atavistic clairvoyance was lost, also as Man’s constitution and nervous system changed (o.a. ancient greek did not see blue, cosmic storm in 15th century, Man’s new organ, ..).

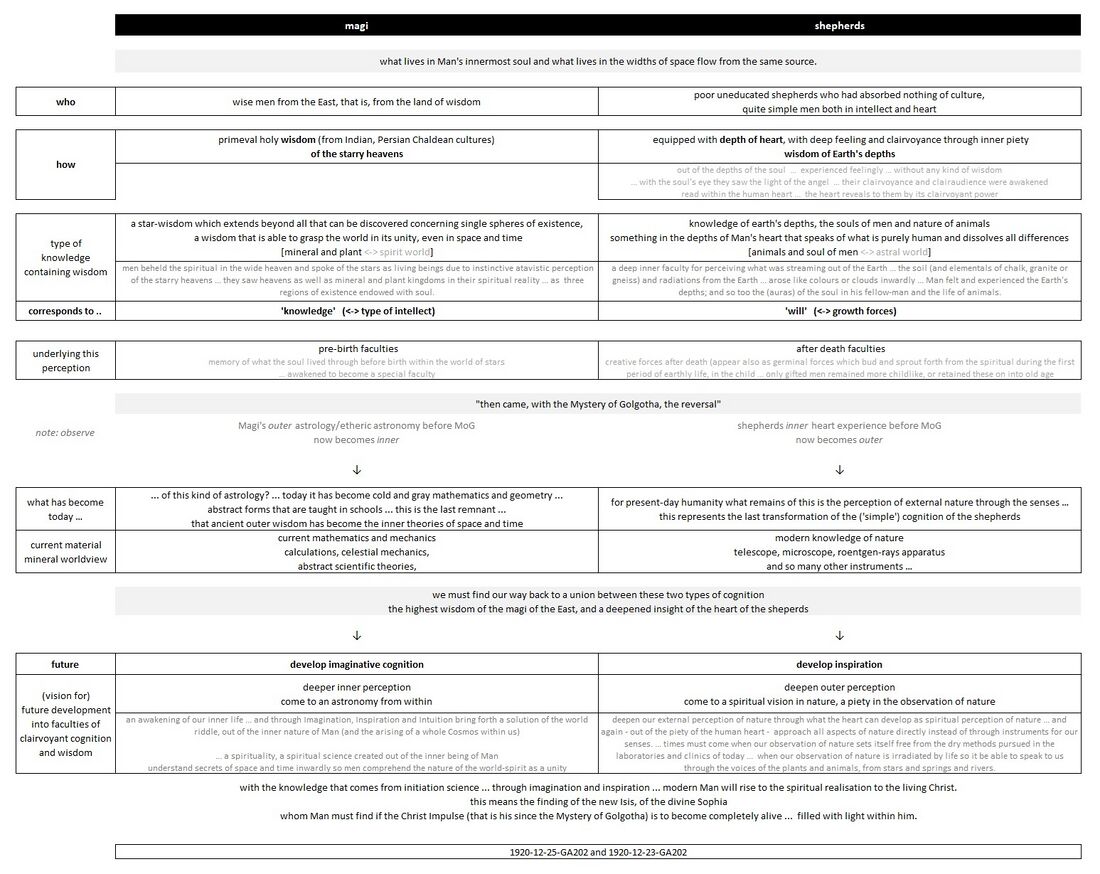

Rudolf Steiner discusses (3) the changes in faculties of cognition before and after the MoG in the lectures of 1920-12-GA202 (23th to 26th). In these lectures the ‘state of soul’ and cognitive faculties are described with the polarity of magi and shepherds (which links to (2) above) and the 'reversal' that came with the Mystery of Golgotha. From the current situation of waking consciousness, future development is described towards a 'new clairvoyance' and wisdom, through conscious cognition of the astral and spirit worlds, see stages of clairvoyance (imagination and inspiration). See also Schema FMC00.617A.

In context of remembrance (between the third and fifth cultural ages) Rudolf Steiner (4) then describes this development as the search of a 'new Isis' or Sophia wisdom. That is: the recreation of the ancient Egyptian legend of Isis (the killed Osiris was sought by Isis) from the third cultural age, but for the context the current fifth cultural age (where Isis-Sophia has been killed by Lucifer (Ahriman)).

On the side, note that the 'new Isis' idea already appeared in 1918-01-17-GA180 in the context of describing the Representative of humanity statue.

Above: the picture (5) is based on Schema FMC00.054, a blackboard drawing (BBD) by Rudolf Steiner; of which variant Schema FMC00.054A provides the key explanatory text annotations from the lecture, which also describes the above in a nutshell. See also the related Schema FMC00.612 (not shown). Importantly, the new wisdom will have a moral component which is missing from the current contemporary consciousness and mineral science, with huge implications for human civilization.

Last, and essential for each human being, note that (6) whereas in ancient ages the cognitive development process was 'outside-in', the new and future process is 'inside-out'. In the language of the grail, the ancient pagan mysteries relate to the Arthur stream (outside-in, nature and spiritual world to Man, also external initiators) whereas Parsifal is the symbol of the new inside-out approach (Man's inside connects to spiritual world, self-initiation) - as depicted with the pictograms from Schema FMC00.380. See also the words in italic in the text box lower right (quoted by RS from 1904-GA010 Ch 2).

In summary (grey boxes under the BBD): the old wisdom Sophia was lost, humanity is now going through a interim phase, but future moral wisdom will be developed by Man through his inner path and connection with the spiritual, a path and work consciously chosen by Man out of freedom and the consciousness soul. This is the path of the spirit-self towards the 'Christ in me' life-spirit. Hence the quote: "initiation is the only possibility for the further progress of humanity" (1920-01-17-GA196).

Schema FMC00.695: shows how the magi and shepherds represent two types of human constitution and cognitive faculties of ancient atavistic clairvoyance from which followed knowledge of the spiritual in the kingdoms of nature and the cosmos. Going down, it shows what has become of these faculties today after the Mystery of Golgotha, and what is to become of this in the future with the arising of conscious clairvoyance that will bring back the knowledge of the spiritual through knowledge of the astral and lower spirit worlds.

See also related Schema FMC00.694 and the lectures on the ancient Sophia wisdom and the finding of the new Isis wisdom.

Regarding the spiritual influences, compare also with the related Schema FMC00.649A

Mysteries of Spirit, Son and Father

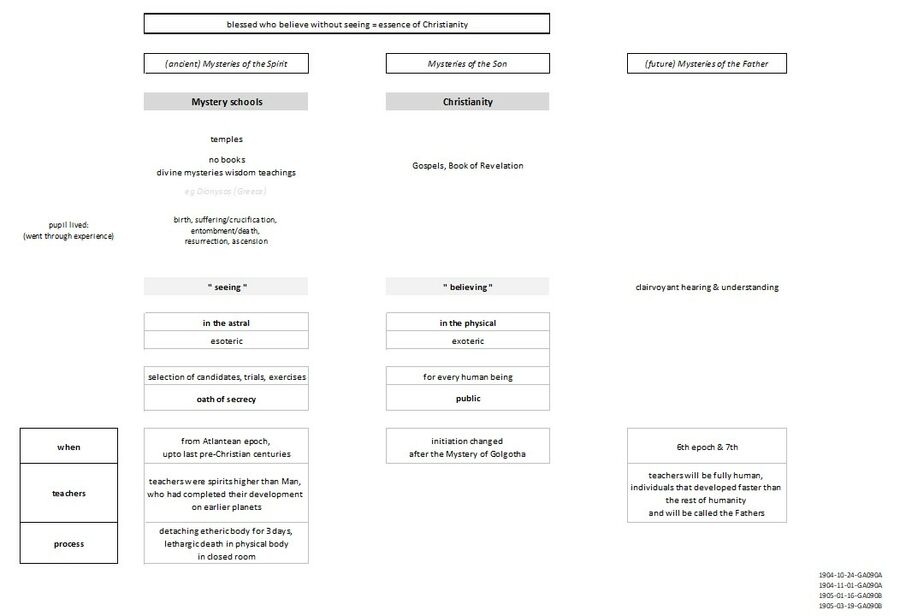

Schema FMC00.397: captures the essence of the Christianity and the statement 'blessed who believe without seeing'. Seeing refers to the astral experience during the initiation process, a tradition for many thousands of years, since the Atlantean mysteries and the cultural ages before Christ.

What happened in the three years of Christ Jesus was a public enactment of what the pupil lived through during the old initiation processes, and these are also the stages in the life of Christ to be found in the Gospels.

See coverage on: Initiation in ancient mysteries and after the Mystery of Golgotha

Note: the schema is based on early lectures on the Book of Revelation. See also Schema FMC00.100.

Lecture coverage and references

Overview coverage

- GA087 of October 1901 to April 1902 sketches the lineage from Heraclitus via Pythagoras and the Greek philosophers (Parmenides, Empedocles, Plato, Socrates), Philo of Alexandria and connecting this with the writers of the four gospels, the school of Paul and Dionysus Areopagite and down to Scotus Eriugena. Connecting in the underlying stream of Christ in Egyptian, buddhist, Greek myths and spiritual life.

- GA008, the book 'Christianity as a mystical fact' (1902)

- GA237, GA238 and GA240 contain the lectures of the period between 1 July upto 16 September 1924 in which the Michael School was sketched from the time of Plato and Aristotle, over the School of Chartres, upto the anthroposophical movement; not just on earth but also in the supersensible world, and including the inspiration by individualities from the spiritual world.

Reference extracts

1901-GA008

Augustine relates how he achieved spiritual vision. Everywhere he asked where the "divine" was to be found.

"I asked the earth and it said, I am not He; and all things that are in the earth confessed the same. I asked the ocean and the depths and all that lives in them, and they answered me: We are not thy God. Seek above us. I asked the fleeting winds, and the whole air, with all its inhabitants made answer: The philosophers who seek for the essence of things in us are deceived. We are not God. I asked the heavens, the sun, moon and stars, and they said: Neither are we the God whom thou seekest."

And Augustine perceived that there is but one thing which can answer his question about the divine: his own soul.

...

One of his most significant utterances is the following:

"What is now called the Christian religion already existed among the ancients, and was not lacking at the very beginnings of the human race. When Christ appeared in the flesh, the true religion already in existence received the name of Christian"

(Augustinus, Contra Faustum 33:6)

190X-GA034

from 'Luzifer' and 'Lucifer-Gnosis' magazines 1903-1908

DE version PDF p. 272-27

The religions are true, but the time has passed for many people when understanding was possible only through faith

Myths, legends, religions are the various ways in which the highest truths have been passed on to the majority of humanity.

This should continue, if it were sufficient. But it is no longer so. Humanity has now reached a stage of development in which a large part would lose all religion if the higher truths on which it is based were not proclaimed in such a form that even the sharpest mind can consider them valid.

The religions are true, but the time has passed for many people when understanding was possible only through faith. And the number of people for whom this is true will increase with unprecedented rapidity in the near future. Those who really know the laws of human development know this.

If the wisdom underlying religious ideas were not openly proclaimed in a form that would stand up to perfect thought, then complete doubt and disbelief in the invisible world would soon arise. And a time when this were the case would be, in spite of all material culture, a time worse than barbarism. Anyone who knows the real conditions of human life knows that man can no more live without a relation to the invisible world than a plant can live without nourishing juices.

1913-10-01-GA148

quote A

Let's then approach the other side of these thoughts. I have often spoken here in this city about the meaning of the Christ idea. And in books and lecture cycles we find diverse elaborations from spiritual science about the secrets of the Christ Being and the Christ concept. Each must come to the conclusion that when he absorbs what is contained in our books and lecture cycles a large amount of knowledge is required for a full understanding of the Christ Being; that one must depend on the profoundest concepts and ideas for a full understanding of what Christ is and what the impulse is which has traversed the centuries as the Christ-Impulse.

One could even come to the conclusion – were it not otherwise contradicted – that it is necessary to know all of theosophy or anthroposophy in order to work one's way up to a correct concept of Christ.

If we put that aside though, and look at spiritual development during the past centuries, we see from century to century a detailed, well-grounded science with the goal of understanding Christ and his appearance on earth. For centuries men have utilized their highest, most meaningful ideas in order to understand Christ.

Here also it would seem that only the most significant intellectual activity would be sufficient to understand Christ. Has it been the case though? A very simple consideration can prove that it has not.

Let us place on a spiritual balance

- all that has contributed until now to the understanding of Christ by scholarship, science, also anthroposophy. Let us place all that on one scale of the spiritual balance

- and let us place on the other scale in our thoughts all the deep feeling, all the impulses in people's souls which have aimed at what we call Christ,

... and we will find that

- all the science, all the scholarship, even all the anthroposophy which we can muster to explain Christ, surprisingly springs up,

- and all the deep feelings and impulses which have directed people to the Christ Being push the other scale far down.

It is no exaggeration to say that a tremendous impact has come from Christ and that the knowledge of Christ has contributed least to this impact.

It would have gone most badly for Christianity if people had to depend on all the learned disputes of the Middle Ages, the Scholastics, the Church fathers; or if people were only to depend on what we are able to muster through anthroposophy for an understanding of the Christ idea. If that were all, it would be very little indeed.

I don't think that anyone who has objectively followed the path of Christianity through the centuries could seriously contest these thoughts.

[Impact of evolution of thinking]

Let us direct our attention to the times when Christianity did not yet exist. I need only remind you of what most of you are familiar with. I need only remind you of the Greek tragedies in ancient Greece, especially in their older forms, when they presented the battling gods, or the men in whose souls the battling gods acted; also how the divine forces were directly visible on the stage. I need only to indicate how Homer thoroughly weaved his significant poetry with the working of the spirit; I have only to point to the great figures of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle. With these names a spiritual life of the highest order appears before our souls. If we put all else aside and look only at the great figure of Aristotle, who lived centuries before the founding of Christianity, we realize that in a certain sense no increase, no advancement has taken place up to our time. Aristotle's thinking, his scholarliness is so awesome that it is possible to say that he reached a peak in human thinking which has not been improved upon until now.

And now for a moment we would like to consider a curious hypothesis, one which is necessary for the following days. Let us imagine that there are no Gospels from which we can learn something about Christ. We want to imagine that the documents known as the New Testament do not exist, that there are no Gospels. We will ignore what has been said about the founding of Christianity and will only consider the facts about Christianity's historical process in order to see what occurred during the following centuries. This means that without the Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, the Pauline Letters and so forth, we only want to consider what has really happened. This is of course only a hypothesis. What has happened?

If we look first at Southern Europe, we find a profound spiritual development at a certain point in time, as we have just seen in its representative Aristotle – a highly developed spiritual life, which in the subsequent centuries went through a special schooling. Yes, at the time Christianity began to make its way through the world there were many people educated in the Greek way, people who had absorbed Greek culture. Even including a certain unusual man who was an energetic opponent of Christianity, Celsus, and who later persecuted the Christians. We find in the Italian sub-continent up to the second, third Christian century, highly educated men who adopted the profound ideas which we find in Plato, whose brilliance really appears as a continuation of Aristotle's brilliance – refined, strong figures with Greek culture – Romans with Greek culture, which added Greek cultural delicacy to Roman aggressiveness.

The Christian impulse pushed itself into this world. At that time the representatives of the Christian impulse were truly uneducated people in respect to intellectuality, to knowledge of the world, compared to the many Greek-Roman educated people. People without education pushed into the middle of a world of mature intellectuality. And now we can observe a strange scene: those simple, primitive natures who were the bearers of early Christianity were able to propagate it in a relatively short time in Southern Europe. And when we approach these simple, primitive souls who at that time spread Christianity, we may say: Those primitive natures understood the Being of Christ. (We don't have to consider the great cosmic Christ thoughts, but only much simpler Christ thoughts.) The bearers of the Christ impulse who entered into the arena of highly developed Greek culture didn't understand it at all. They had nothing to bring to the market of Greek-Roman life except their personal inwardness, which they had developed as their personal relationship to their beloved Christ; for they loved as a member of a beloved family just through this relationship. Those who brought Christianity to Greece and Rome were not educated theosophists; they were unlettered. The educated theosophists of that time, the Gnostics, had elevated ideas about Christ, but they could only give what we would have to place on the rising scale of the weighing balance. If it had depended on the Gnostics, Christianity would surely not have made its way through the world. It was no particularly educated intellectuality which came from the east and in a relatively short time brought ancient Greece and Rome to their knees. That's one side of the story.

From the other side we see intellectually superior people such as Celsus, Christianity's enemy, and even the philosopher on the throne, Marcus Aurelius, who used every contrary argument imaginable. Look at the immensely learned Neo-Platonists, who formulated ideas compared to which contemporary philosophy is child's play, and which surpasses our current ideas in profundity and horizon. And look at how these highly cultured people argued against Christianity, how they argued from the standpoint of Greek philosophy, and we have the impression that none of them understood the Christ-impulse. We see that Christianity was spread by bearers who understood nothing of the essence of Christianity; it was fought against by a high culture which could not understand what the Christ-impulse meant. It is noteworthy that Christianity entered the world in such a way that neither its adherents not its enemies understood its underlying spirit. Nevertheless those people had the strength in their souls to spread the Christ-impulse triumphantly throughout the world.

[Tertullian]

And such as Tertullian, who represented Christianity with a certain greatness. We see in him a Roman who was in fact, when we look at his language, almost a re-creator of the Roman language, who with an unerring accuracy enlivened words to the extent that we recognize him as an important personality. When we ask ourselves, however, about Tertullian's ideas, it's something else. We find that he showed very little intellectuality or high culture. Even Christianity's defenders didn't accomplish much. Nevertheless, such as Tertullian were effective, effective as personalities, for which reason educated Greeks could not really do much.

He was awe-inspiringly effective through something. But what? That is the important thing. We feel that this is really all important.

Through what did the bearers of the Christ-impulse work when they themselves didn't understand much about what the Christ-impulse is? Through what did the Christian Church Fathers work, even Origenes, who is considered unskillful. What is it that even Greek-Roman culture could not understand about the essence of the Christ-impulse? What is it all about?

But let's go farther. The phenomenon becomes more pronounced as we consider subsequent history. We see how over the centuries Christianity spread within Europe to peoples who, like the Germanic, derived from completely different religious traditions and who were united as a people, or at least seem to be united in their religious traditions. Nevertheless they accepted the Christ-impulse with all their strength, as though it were their own life. And when we consider the most effective messengers of faith in the Germanic peoples – were they the scholastic theologically educated ones? By no means! They were relatively primitive souls who went about among the people and in a primitive way, using ordinary ideas, speaking to the people, and captured their hearts completely. They knew how to use words in such a way that they touched the deepest heart strings of their listeners. Simple people went out to all regions, and it was they who worked most effectively.

So we see the spread of Christianity over the centuries. But then we wonder at how this same Christianity is the grounds for so much significant scholarship, science and philosophy. We don't underestimate this philosophy, but today we want to direct our attention to an extraordinary phenomenon — that up until the Middle Ages Christianity spread among peoples who had quite other ideas in their minds, until it belonged to their souls.

And in the not too distant future still other things will be emphasized about the spread of Christianity. When we consider the effect of the Christian impulse, it is easy to understand that in a certain time enthusiasm arose through the spreading of Christianity. But when we come to modern times this enthusiasm seems to be muted.

...[cont'd see lecture]

quote B editor note: observe in this extract, the difference when reading such phrasing as .. Christ as a spiritual being 'him' (with capitals everywhere in the original for He and Who .. here removed) .. versus the 'Christ Impulse' as a cosmic principle (budhi-Christos). What is it that spreads, versus who.

Christianity has spread irrespectively of the views of its adherents or opponents, even appearing in an inverted form in the domain of modern materialism.

But what exactly is it that spreads?

It is not the ideas nor is it the science of Christianity; nor can we say that it is the morality instilled by Christianity.

Think only of the moral life of men in those times and we shall find much justification for the fury levelled by men who represented Christianity against those who were its real or alleged enemies.

Even the moral power that might have been possessed by souls without much intellectual education will not greatly impress us.

What, then, is this mysterious impulse which makes its victorious way through the world?

Let us turn here to spiritual science, to clairvoyant consciousness.

What power is at work in those unlearned men who, coming over from the East, infiltrated the world of Greco-Roman culture?

What power is at work in the men who bring Christianity into the foreign world of the Germanic tribes?

What is really at work in the materialistic natural science of modern times, the doctrines of which disguise its real nature?

What is this power?

It is Christ himself who, through the centuries, wends His way from soul to soul, from heart to heart, no matter whether souls understand him or not.

It behoves us to leave aside the concepts that have become ingrained in us, to leave aside all scientific notions and point to the reality, showing how mysteriously Christ himself is present in multitudinous impulses, taking form in the souls of thousands and tens of thousands of human beings, filling them with his power.

It is Christ Himself, working in simple men, who sweeps over the world of Greco-Roman culture; it is Christ himself who stands at the side of those who in later times bring Christianity to the Germanic peoples; it is he - Christ himself in all his reality - who makes his way from place to place, from soul to soul, penetrating these souls quite irrespectively of the ideas they hold concerning Him.

1917-04-10-GA175

What did Christ Jesus mean by faith or trust?

We have a far too theoretic, a far too abstract conception of faith today. Consider for a moment Man’s usual conception of faith when he speaks of the antithesis between faith and knowledge. Knowledge is that which can be demonstrated or proved; faith is that which is not susceptible of proof, and yet is held to be true. It is a question of the particular way in which we know or understand something. It is only when we speak of knowledge as faith or belief that we think of it as something which is not susceptible of final proof.

Compare this idea of faith with the conception which Christ Jesus preached. Let me refer you to this passage in the Gospels:

“If ye have faith and doubt not … but also if ye shall say unto this mountain, Be thou removed and be thou cast into the sea; it shall be done.” (Matt. XXI, 21)

How great is the contrast between this conception of faith, paradoxically yet radically expressed in the words of Christ, and the present-day conception which in reality sees in faith simply a substitute for knowledge.

A little reflection will show what is the essence of Christ’s conception of faith. Faith must be an active force, a force that accomplishes something. Its purpose is not simply to evoke an idea or to awaken knowledge. He who possesses faith shall be able to move mountains.

If you refer to the Gospels you will find that wherever the words “faith” or “trust” appear, they are associated with the idea of action, that one is to be granted a power through which something can be effected or accomplished, something that is productive of positive results. And this is extremely important.

1917-04-17-GA175

regarding the spreading of Christianity, and the role of emperor

see Schema FMC00.673 regarding Tiberius, the second Roman emperor (AD 14 until 37) and adopted son of stepfather emperor Augustus, married Julia the Elder (KRI 41), Augustus' only biological daughter Julia. Tacitus (KRI22) wrote about Tiberius reign. According to the Gospels, Jesus preached and was executed during reign of Tiberius; John the Baptist entered his public ministry in the 15th year of Tiberius' reign.

Rudolf Steiner commented on several contemporary souls of this period Augustus-Tiberius.

I have often spoken to you of the remarkable fact that the early Roman emperors acquired Initiation by constraint and this explains many of their actions. Consequently they gained knowledge of certain facts connected with the great impulses of cosmic events, but they exploited this knowledge derived from the Mysteries to their own advantage.

It is most important to realize that the intervention of the Christ Impulse into the historical life of mankind was not merely an event on the physical plane which we can apprehend through a study of the historical facts, but was a genuinely spiritual event. I have already pointed out that the Gospel report that Christ was known to the devils has deeper implications than is usually recognized. We are told that Christ performed acts of healing which are described in the Gospels as the casting out of evil spirits. And we are constantly reminded that the devils knew who Christ was. On the other hand Christ Himself rebuked the devils and “suffered them not to speak for they knew He was the Christ.” (Mark I, 34; Luke IV, 41). The appearance of Christ therefore was not only a matter for the judgement of men. It is possible that at first people did not have the slightest inkling of what the coming of Christ presaged. But the devils—beings belonging to a super-sensible world—recognized Him. The super-sensible world therefore knew of His advent. The more informed leaders of the early Christians were firmly convinced that the coming of Christianity was not merely an event on the terrestrial plane but something that was related to the spiritual world, something which evoked a radical change in the spiritual world. Without a shadow of doubt the leading spirits of early Christianity were firmly persuaded of this.

Now it is a remarkable phenomenon that the Roman emperors, because of their forced initiation which gave insight into the spiritual world, had a presentiment of the far-reaching importance of the Christ Impulse. There were some emperors. however, who despite their irregular initiation, understood little of these secrets; but there were others who understood so much that they were able to divine something of the power and effectiveness of the Christ Mystery. And it was these more talented, the more perspicacious emperors who began to pursue a definite policy towards Christianity which was then gaining ground. Indeed the first emperor to adopt this policy was Tiberius who succeeded Augustus, though the objection might be raised that Christianity was not as yet widely diffused. This objection, however, is not valid for, when he learned of Christ's birth in Palestine, Tiberius—who had received a partial initiation into the ancient Mysteries—realized its significance.

Let us consider for a moment that policy towards Christianity which began under Tiberius and was pursued by all the initiated emperors. Tiberius announced his intention to admit Christ to the Roman pantheon.

The Roman empire pursued a deliberate policy towards the worship of the gods. In essence it was as follows: when the Romans conquered a people they received the gods of the newly conquered people into their Olympus. They declared that these gods were also deserving of veneration and they were added to the Roman pantheon. The object of this policy therefore was to appropriate not only the material or temporal goods, but also the spiritual forces of the conquered peoples. The initiated Caesars saw in the gods something more than the mere external images; they had a deeper understanding than the people. They knew that the visible image of the gods concealed real spiritual powers pertaining to the different hierarchies. Their policy was perfectly consistent and comprehensible, for the authoritarian principle of Rome was consciously reinforced by the power which was believed to derive from the assimilation of other gods. And, as a rule, the worship of other gods was accepted not only in an outward and exoteric way, but the Mystery-teachings of other peoples were also taken over by the Roman Mystery-centres and merged with the Mystery-cult of the ancient Roman empire. And since, at that time, it was generally held that it was neither right nor possible to govern without the support of the spiritual powers symbolized by the gods, this practice was taken for granted.

The aim of Tiberius therefore was to integrate the power of Christ, as he conceived it, with the impulses proceeding from the other deities recognized by him and his peoples. The Roman Senate thwarted his intention and nothing came of it. None the less the initiated emperors, Hadrian among them, made repeated efforts to achieve this goal, but constantly met with opposition from the dignitaries who could make their influence felt. And when we examine the objections raised against this policy of the initiated emperors we can form a good idea of what happened at this decisive turning-point in human evolution.

We witness here a remarkable coincidence. On countless occasions Roman writers, influential personalities and large sections of the Roman populace accused the Christians of profaning what others held to be sacred, and vice versa. In other words, the Romans repeatedly emphasized that the Christians were radically different in thought and feeling from the Romans and other peoples—for the other peoples together with their gods had been assimilated by the Romans. Thus everyone looked upon the Christians as people with a different make-up, people with different feelings and responses. Now this view could be dismissed as a calumny; suchlike accusations are always ready to hand, of course, when one takes a superficial view of history. But we cannot regard this view as a calumny when we realize that many of the opinions of earlier times and many of the contemporary opinions concerning the Mystery of Golgotha have passed over verbatim into Christian teaching.

To put it more clearly, the Christians expressed their sentiments in words that could be found amongst many of their contemporaries. One of these was Philo of Alexandria, a contemporary of Christ, who probably had first-hand knowledge of what was later found in the Christian writings. Philo makes the following remarkable statement: “According to traditional teachings I must hate that which others love” (he is referring to the Romans) “and love that which others hate.”

If you bear this statement in mind and turn to the Gospel of St. Matthew, you will find countless passages which echo this statement of Philo. And so we can say that Christianity has developed, as it were, out of a spiritual aura which required people to say, “we love what others hate”. This means—and this saying was quoted in the early Christian communities and served as one of the fundamental principles of Christian teachings—that Christians themselves openly acknowledged what others reproached them with. It was not therefore a calumny; it accorded with the Roman view: “the Christians love what we hate and hate what we love”. And the Christians, for their part, said exactly the same of the Romans.

It is clear therefore that something wholly different from anything that had been known before now entered human evolution—otherwise it would not have had so great an impact. Of course, if we wish to understand this whole situation we must realize that the new impulse had come from the spiritual worlds.

Many who were contemporaries of the Mystery of Golgotha, such as Philo, caught fleeting glimpses of it which they described each after his own fashion. And so many of the passages from the Gospels which are interpreted expediently today, as in the case of Barres, whom I mentioned at the conclusion of my last lecture, will be seen in their true light when we cease to interpret them to suit our convenience, but when our interpretation is determined by the whole spirit of the age. There are strange interpretations in Barres; indeed Biblical exegesis assumes very strange forms nowadays.

Much that Philo says agrees closely with the Gospels and I would like to quote a passage which shows that because he was not inspired to the same extent as were the Evangelists later, his style was rather different from theirs. As a talented writer in the popular sense he made less heavy demands upon the reader than the Evangelists. In one notable passage Philo gave expression to something that was occupying the hearts and minds of the men of his time. He says:

“Do not concern yourselves with the genealogical records or the documents of despots, take no thought for the things of the body; do not attribute to the citizen civic rights or civil liberties, which you deny to those of humble origin or who have been purchased as slaves in the market, but give heed only to the ancestry of the soul!”

If the Gospels are read with understanding one cannot fail to recognize that something of this attitude of mind, albeit raised to a higher level, pervades the Gospels and why therefore an opportunist like Barres can write the passage I quoted to you in my last lecture. We should do well to bear his words in mind and I propose therefore to read them to you once again.

1918-10-06-GA184

And now we want to bring before our souls something which in some measure is suited to spread light over the Mystery of Golgotha from another point of view. I have in mind two phenomena about which I said a few words during our studies of the day before yesterday. These two phenomena in the life of mankind are, first,

- the phenomenon of death, and secondly

- the phenomenon of heredity — death which is connected with the end of life, and heredity with birth.

...

If the Mystery of Golgotha had not come about, Man would have been able to gain only false conceptions about heredity and about death.

...

[Two key facts related to MoG]

Hence two facts that are inseparable from a true view of the Mystery of Golgotha are those which form, as it were, its boundaries: namely,

- the Resurrection, which cannot be understood independently of

- the Virgin Birth — born not in the way that makes birth a delusive fact few mankind, but born in a supersensible way and going through death in a supersensible way.

1924-07-13-GA237

see also: Mystery School tradition#1924-07-13-GA237

Even until the 7th or 8th century—in a kind of echo of pre-Christian Initiation—Christianity was taught in centres that had remained as the high places of knowledge, relics of the ancient Mysteries. In those centres human beings were prepared, not so much by way of instruction, but by an education towards the spirit—a training both bodily and spiritual. They were prepared for the moment when they might have at least a delicate vision of the spirituality that can manifest itself in the environment of Man on Earth.

Christianity as religion

1908-05-13-GA102

All this is connected with the stages of development of the human spirit. Only through this anthropomorphism could humanity be prepared to conceive of the God-man, to conceive of God dwelling within man himself. This is why Christianity is also called theomorphism by occultism.

In Christianity, all the different divine figures flow together in the one living figure of Christ Jesus. For this, it was necessary for humanity to undergo a great and powerful deepening, a deepening that enabled humanity not only to think of the living form in space, as expressed in Greek sculpture, but to rise to the idea of seeing inwardness outwardly, to the belief that the eternal in a historical form has really lived on Earth in the spatial-temporal. That is the essence of Christianity. This idea represented the greatest advance that humanity could make on Earth.

- We need only compare the Greek temple, which is a dwelling place of the god, with what later becomes the Christian church, as it is most purely expressed in the Gothic style. We will see that in the external forms there must even be a regression if one wants to represent the eternal in the temporal and spatial. And what later art achieves by expressing the inner in the outer is entirely under the influence of the Christian spiritual current. Basically, it must be said that it is understandable that architecture could become most beautiful where one could still cling with all one's soul to the outer powers that flood through space.

- Thus we see how religious thought becomes ever more profound in the post-Atlantean era, how people seek their clues for the supersensible. It will not be difficult to see in all that has been said here indications of Man's longing to penetrate the outer form, to somehow conjure up the supersensible within it. This is the aim of the most original sources of art. With Christianity we have, so to speak, arrived at our own time. From this and various other things said about the development of the post-Atlantean time, you will recognize that the course of humanity is striving more and more towards internalization. There is also an ever-increasing awareness of internalization in the external in the different races.

- We would like to say that in the Greek images of the gods we see how that which lives within man pours out into the outer world. In Christianity, the most important impulse in this direction has been given. With Christianity, we see the emergence of what has been called science up to the present time. For what is today called science, the investigation of the intellectual foundations of existence, only begins in the Chaldean period. Now, in our time, we are really living in a great turning point in the development of humanity.

If we now survey what we have briefly considered and ask ourselves:

Why did all this happen, why did Man develop to impress the inner on the outer?

the answer is that Man was impelled to do so by the evolution of his organization.

The ancient Atlanteans were able to perceive the supersensible world because their etheric body had not yet been completely drawn into the physical body. A point of the 'ether head' did not yet coincide with the corresponding point in the physical head. The complete penetration of the etheric body with the physical body is the reason why man is now being pushed out more into the outer world.

When the gates to the supersensible world closed, Man needed a bond, a connection between the sensual and supersensible worlds, in his artistic development. In the past, in Atlantean times, he did not need this because at that time he was still able to get to know the supersensible world through direct experience. The gods and spirits had to be related to people only after they had lost their perceptibility, just as one has only to relate plants to people who have never seen them. This is the basis of the religious development of the post-Atlantean period.

Why then did a being of a supersensible nature like Christ have to appear and live on Earth in a finite personality, in Jesus? Why did Christ have to become a historical personality? Why did the eyes of men have to be fixed on this figure? We have said that men could no longer see into the supersensible world. What had to happen so that the God could become an experience for them?

He had to become sensual, to embody Himself in a sensual, physical body. That is the answer to the question. As long as human beings were able to perceive in the spiritual, as long as they were able to perceive the gods there in supersensible experience, no god would have needed to become Man. But now the god had to be there within the sensual world. The disciples' words flowed out of these feelings to affirm this fact: “We have laid our hands in his wounds,” and similar ones.

Thus we see how the appearance of Christ Jesus Himself becomes clear to us from the nature of post-Atlantean men, how we recognize why Christ actually had to reveal Himself for sensory perception. The strongest historical fact had to be there for people. The spiritual self had to be there in a sensory way so that people had a point of reference that could connect them to the supersensible world.

Mere science degenerated more and more into a worship of the external world. Today we have reached a climax in this. Christianity was a strong support against this absorption in the sensual. Today, Christianity must be grasped in theosophical depth in order to be able to present itself to people in a new understanding. In the Middle Ages there was still a connection between science and Christianity. Today we need a supersensible deepening of knowledge, of wisdom itself, in order to understand Christianity in its full depth. So we are faced with a spiritual conception of Christianity. This is the next stage, the theosophical or spiritual-scientific Christianity.

On the other hand, material science will increasingly lose its connection with the supersensible worlds.

What, then, is the task of spiritual science? Can the person seeking the spirit look to today's conventional science?

What today's conventional science is, is precisely that which will increasingly take the course of post-Atlantic development and will increasingly focus only on the external, the physical, the material, and increasingly lose touch with the spiritual world. will lose its connection with the spiritual world. Follow any science back into earlier times: how many spiritual elements were there in it in the past! You will see everywhere, in medicine and in other fields, how the spiritual connection has increasingly disappeared. You can follow this everywhere. And this process must be so, because the process of the post-Atlantic period is such that the original connection with the supersensible world must increasingly be lost. Today we can predict the course of science. Outward science will not, however much experiments are made, be capable of spiritual deepening. It will increasingly merge with that which is a higher instruction in technical skills, a means of mastering the outer world. For the Pythagoreans, mathematics was still a means of looking into the context of the higher worlds, into the harmony of the world; for today's Man, it is a means of further developing technology and thus of mastering the outer world. The course of outer science will be secularized and unphilosophized.

All people will have to draw their impulses from spiritual development. And this spiritual development will take the path to spiritual Christianity. Spiritual science will be that which is capable of giving the impulses for every spiritual life.

Science is increasingly becoming a technical guide. And university life is increasingly sliding over into that of a technical college, and that is the right thing. All spiritual knowledge will develop into a free human possession that must come out of science. Science will then appear again in a completely different context and in a completely different form.

It is therefore necessary for present-day humanity that the re-establishment of the great experiences of the supersensible worlds take place. You can see that it is necessary if you realize what will happen if it does not.

- The etheric head is now drawn into the human being; the connection of the etheric body with the physical body is at the peak of development today. Therefore, the percentage of people who could have supersensible experiences has never been lower. But the course of human evolution moves forward in such a way that a re-emergence of the etheric body occurs all by itself again. And that has already begun. Again the etheric body emerges, it becomes more independent, freer, and in the future it will again be outside the physical body as it was in early times. The loosening of the etheric body must happen again, and that has already begun. But now Man must take with him in his emerging etheric body what he has experienced in the physical body, especially the physical event of Golgotha, which he must experience physically, that is, in an earthly existence. Otherwise, something will be irretrievably lost to him: the etheric body would withdraw without him taking anything essential with it, and such people would remain empty in the etheric body. But those who have fully experienced spiritual Christianity will have in abundance in the etheric body what they have gone through in the physical body.

The greatest danger is for those who have turned away from spiritual truths through scientific deception.

- But the beginning of the emergence of the etheric body has already been made. The nervousness of our time is a sign of this. This will increase more and more if Man does not take with him what is the greatest event in the physical body. There is still a lot of time for this, because for the masses it will take a long time, but some are already arriving at it. But if there were a person who had never gone through what is the greatest event in the physical world, who had never experienced the depth of Christianity and incorporated it into his etheric body, he would face what is called spiritual death. For the emptiness of the etheric body will result in spiritual death.

.

The clairvoyant Atlantean did not need a religion because the experience of the supersensible was a fact for him. All human development originated in such a time. Then the vision of the spiritual world faded. Religere means to connect, and so religion is a connection of the sensual with the supersensible. The time of the rising materialism needed religion. But the time will come when people will be able to have experiences in the supersensible world again. Then they will no longer need religion.

The new vision requires the bringing along of spiritual Christianity, it will be the consequence of Christianity. This is the basis for the sentence that I ask you to remember as particularly important: Christianity began as a religion, but it is greater than all religions.

What Christianity has given will be taken along into all times of the future and will still be one of the most important impulses for humanity when religion as such no longer exists. Even when people have overcome religious life, Christianity will remain.

That it was first a religion is connected with the development of humanity; but Christianity as a world view is greater than all religions.

other translation of last paragraph

The necessary antecedent of the new vision is that human beings shall be bearers of spiritual Christianity. This is the basis of the sentence of which I would ask you to realize the profound significance: Christianity began as a religion but is greater than all religions.

What Christianity bestows goes with us into all ages of time to come and will still be one of the essential impulses in humanity when religion, as we know it, is no longer in existence. Even when religion, as such, has been transcended, Christianity will remain.

The fact that it was first of all a religion is connected with the evolutionary process of humanity. But Christianity as a world view is greater than all religions.

1922-04-13-GA211

It was evident from our recent lectures that anthroposophy has much to render in the way of service to the humanity of our time. A significant service which it can render will be that of religion. But we do not intend to inaugurate a new religion!

The event which has given the Earth its meaning is of such a character that it will never be surpassed. This event consists in the passing of a God through the human destiny of birth and death.

After the advent of Christianity no new religion can be founded - this is evident to anyone who knows the foundation of Christianity. We would misunderstand Christianity were we to believe that a new religion could be founded.

But since humanity itself advances more and more in super-sensible knowledge, there will be an ever deeper comprehension of the Mystery of Golgotha, and with it of the Christ Being.

To this comprehension anthroposophy wishes to give, at the present time, what it alone is capable of contributing; for nowhere else will there be the possibility of speaking about the estate of the divine teachers of humanity in primeval times who spoke of everything except birth and death, because they themselves had not passed through birth and death. And nowhere else will it be possible to speak of the Teacher Who had come to His initiated disciples in a form similar to the one in which the divine primeval teachers of mankind had once appeared, but Who was able to give the significant teachings of a God's experience in the human destiny of birth and death.

Discussion

DRAFT WORK NOTE

Sources: early Christian texts

1. The Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke)

The Synoptic Gospels—written between approximately 65–90 CE. Mark, likely the earliest (c. 65–70 CE),

Jesus is not explicitly proclaimed as equal to God but more is a divinely anointed human whose authority derives from God.

2. The Gospel of John

Written likely in the 90s CE, John offers the most overtly theological and mystical vision of Jesus as the pre-existent Logos (Word), "with God and was God" (John 1:1). The Johannine Christ is not only sent by God but shares in God's divine essence. His miracles are signs, revelations of his divine identity, and salvation comes through believing in him—trusting his divine nature and mission. The cross, far from a moment of defeat, is a moment of glorification.

3. Paul’s Letters

Paul's letters, written in the 50s and 60s CE, are the earliest Christian writings. Jesus is the crucified and risen Lord, exalted by God, but not equal to God in the Trinitarian sense developed later. Jesus is divine in function as mediator, savior, but still subordinate to "the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ."

4. The Gospel of Thomas

This sayings gospel, unearthed in the Nag Hammadi Library and dated possibly as early as 50–100 CE, presents Jesus as a wisdom teacher rather than a savior through death. There is no crucifixion, resurrection, or virgin birth. Jesus guides his disciples to self-realization: "If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you" (Saying 70). The kingdom is "within and among you."

5. The Gospel of Mary Magdalene

This text, though fragmentary and later (2nd century), elevates Mary Magdalene as the disciple who truly understood Jesus. It challenges Peter’s authority and promotes inner spiritual ascent as the path to salvation. There is no crucifixion narrative, no resurrection appearances in bodily form; instead, Jesus is a revealer of higher realms.

6. Acts of the Apostles

Acts presents a more unified, hierarchical picture of the early church. Written by the same author as Luke, it emphasizes continuity between Jesus and his followers, the role of the Holy Spirit, and the apostolic mission. Jesus ascends bodily; salvation is extended to Gentiles through faith and baptism.

7. The Letter of James

James focuses little on Jesus’ divinity and nothing on his death or resurrection. Instead, it emphasizes moral action: “faith without works is dead” (James 2:26). Jesus is a moral teacher more than a savior, resembles the ethical sage of the Sermon on the Mount. There is no mention of virgin birth or cosmic logos.

8. The Didache

The Didache (Teaching of the Twelve Apostles), likely from the late first or early second century, is a practical church manual rather than a theological treatise. Jesus is honored as Lord and teacher, but not explicitly divine. There is no mention of a virgin birth, nor an atonement theology. Instead, the text emphasizes baptism, the Eucharist, ethical living, and community cohesion. (reflects Jewish-Christian milieu valuing simplicity and obedience).

9. Revelation

John of Patmos presents a Jesus who is cosmic, triumphant, and apocalyptic. He is the Lamb who was slain, the Alpha and Omega, and divine judge. While Jesus is still distinguishable from God the Father, he is worshipped and acts as the eschatological ruler.

Theological Divergences: Birth, Divinity, Death, Salvation

- Virgin Birth: Only Matthew and Luke affirm this. Paul, John, Mark, and the Gnostic texts are silent. The idea gains theological traction post-100 CE, symbolizing divine origin more than biological fact.

- Divinity: Only the canonical gospel of John and Revelation elevate Jesus to near-equal status with God. Paul suggests functional divinity, while Synoptics are more reticent. Gnostic texts speak of divine spark, but not incarnation in the orthodox sense.

- Death: Paul and the Synoptics see the crucifixion as central to salvation. John transforms it into glorification. Gnostic texts do not focus on it. For some Jewish-Christian texts, Jesus’ death is tragic but not salvific, as part of a movement to end corruption and animal sacrifices in the Temple.

- Salvation: Varies widely—by faith (Paul), ethical action (James), mystical knowledge (Thomas), sacramental participation (Didache), or apocalyptic endurance (Revelation). No consensus existed in the first two centuries.

- Gender, Women, and the Sacred Feminine

Early Christianities diverged radically on gender. Paul includes women like Junia and Phoebe, while later texts (1 Timothy, possibly pseudonymous) restrict women’s roles. The Gospel of Mary and other Gnostic works elevate the feminine, often associating divine wisdom (Sophia) with female figures. The Orthodox canon downplays these elements, and by the second century, the sacred feminine is increasingly marginalized.

The suppression of Gnostic and visionary texts by the proto-orthodox bishops (Irenaeus, Tertullian) included the erasure of female spiritual authority and the alignment of orthodoxy with male apostolic succession.

The Rise of Competing Christianities (100–300 CE)

By the second century, competing schools crystallized:

- Proto-Orthodox Christianity (Ignatius, Irenaeus): Emphasized apostolic succession, bodily resurrection, Jesus as fully God and fully man, and ecclesiastical hierarchy. Canon formation began in earnest aligned with Paul's letters.

- Gnostic Christianity (Valentinians, Sethians): Focused on inner illumination, Jesus as revealer of hidden knowledge, and salvation through awakening & import of developing both sacred feminine and masculine. These communities were diverse, often egalitarian, women were given equal opportunity.

- Jewish-Christian sects (Ebionites): Saw Jesus as a prophet, but not divine; upheld Torah observance and rejected Paul - The Ebionites were aligned with the book of James.

- Montanists and Charismatics: Emphasized prophecy, visions, and female leadership (e.g., Priscilla, Maximilla). They were eventually declared heretical for bypassing episcopal control.

Conclusion

The Jesus of history and the Christ of faith were profoundly malleable figures in the early centuries of Christian thought. From an ethical Jewish teacher to a cosmic savior, from a political revolutionary to a Gnostic revealer of divine mysteries, Jesus was interpreted in ways that reflected the needs, cosmologies, and conflicts of diverse communities. The eventual triumph of one version—articulated by bishops, councils, and imperial power—obscured this early richness. Yet in recovering these texts today, we glimpse the full spectrum of spiritual and theological possibility that marked the first 300 years of Christianity: a movement as plural as it was passionate, as revolutionary as it was redemptive.

Related pages

- Christ - base study modules 1 to 7

- Christ - study modules 14 to 21

- Christ Module 6 – the principle in image metaphor story

- Archangel Michael

- The Michaelic stream

- Gospels

References and further reading

- Annie Besant: 'Esoteric Christianity, or The Lesser Mysteries' (1898) - free PDF download

- Walter Bauer (1877-1960): 'Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity' (1971 in EN, original in DE 1934 as 'Rechtgläubigkeit und Ketzerei im ältesten Christentum'

- Bauer developed his thesis that in earliest Christianity, orthodoxy and heresy do not stand in relation to one another as primary to secondary. In many regions, beliefs that would be considered heresy centuries later were the original and accepted form of Christianity.

- Andrew J Welburn: 'The Beginnings of Christianity: Essene Mystery, Gnostic Revelation and the Christian Vision' (1991)

- Bastiaan Baan, Christine Gruwez, Philip Mees, John van Schaik: Sources of Christianity: Peter, Paul and John' (2017 in EN)