Rudolf Steiner's Gesamtausgabe (GA)

The Gesamtausgabe (GA) - or in English, Collected Works (CW) - of Rudolf Steiner's foundational contribution to spiritual science encompasses some 100.000 pages and consists of over 350 volumes. The majority of the content are the 4550 lectures with notes, from the 6200 lectures given in over 120 cities and 13 countries in the period between 1904 and 1924.

Initially, Marie Steiner von Sivers took care of Rudolf Steiner's work during his life starting with initial publishing as of 1902, taking up major editorial and publishing work in earnest around 1916 and continuing this until her death in 1948. In 1943 she founded the "Rudolf Steiner Nachlassverwaltung' and in 1947 transferred all rights to Steiner's works to it after disputes and lawsuit with the Anthroposophical Society (AAG) over the publishing rights for the work of Rudolf Steiner.

The first ideas for the Gesamtausgabe in 1947 were developed into a first plan in 1953, with the first releases starting in 1957, and the GA was officially established as a publishing initiative in 1961 based on the foundational plan by Hella Wiesberger of that year. In 2015-16 the so-called GA2025 was started to try and finish publication of Steiner's work by 2025.

Hence the history of publishing Rudolf Steiner's contribution can be seen in three periods: the period Marie Steiner 1902 to 1948 (46 years), the continuation 'pre-GA' up to 1961, and the GA period 1961 to 2025 (64 years). During this time multiple initiatives in various countries started translation and publication in multiple languages.

History of the GA

Introduction

Rudolf Steiner gave more than 6200 lectures in over 120 cities and 13 countries across Europe in the period between 1904 and 1924. The exact number varies depending on the source, as no records are available for about a quarter of all lectures. Hence the figures below should be considered indicative and corresponding to reality, but not necessarily of digital accuracy.

Though he traveled across Europe, analysis shows that the base location from which the majority of lectures were given was Berlin before the first world war WWI (1669 lectures), and moved to Dornach during and after WWI (1813 lectures), with Stuttgart being the third main location especially after WWI (761 lectures). In total 65% of all lectures were held in these three locations Berlin, Dornach and Stuttgart (4274 of 6651). At the peak between 100 and 300 lectures per year were held in these locations, in other years between 30 and 70. The fourth major location is Munich, especially before WWI (302 lectures). So approx 70% of all lectures was held in those four locations (4576 of 6651 or 69%). After this follows Basel and Leipzig also with over 100 lectures in total.

To connect to the atmosphere of Berlin in this period 1900-1910 where Steiner held many important lecture cycles, you can view for example the first 3 minutes of the following movies on youtube - movie A and movie B - of Berlin in the beginning of last century. This site also has a download version of the short excerpt in case the video goes offline.

A second movie - here on youtube - contains similar footage of various European cities. The major cities in this movie that Rudolf Steiner traveled to around this time were Paris (37 lectures 1906-1924) , London (38 lectures 1902-1924, of which 28 in 1922-24) , Amsterdam (14 lectures, of which 7 in 1921), Stockholm (31 lectures in 1908-13).

There are some periods of say twenty seconds in these short 'evocation' movies that allow one to transpose one's mind to this period when Steiner walked around on these streets to his lectures. For people who know they were incarnated in this period, this may arouse a certain soul feeling

For a breakdown of the GA in the various elements both in terms of format and contents, we refer to the sources below. Not focusing on the written works or artworks, the focus on this site is predominantly on the thousands of lectures that constitute the bulk of the available written materials on spiritual science.

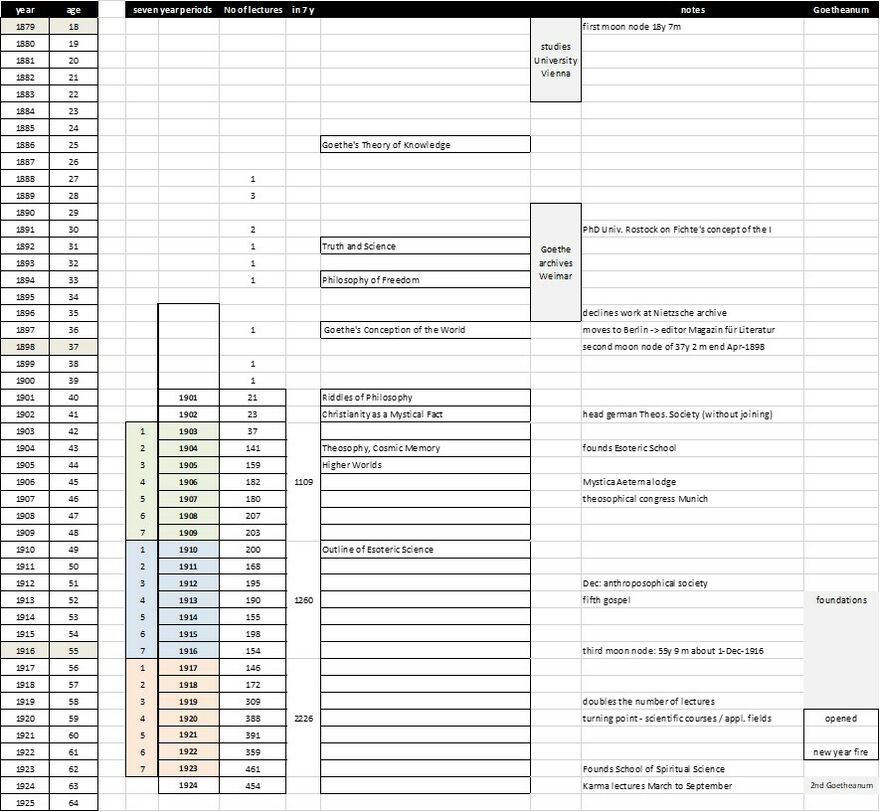

Rudolf Steiner's life timeline

Schema FMC00.124 gives an overview on Rudolf Steiner's adult life and especially his lecturing activity in the three main seven year periods (in colour), the three moon nodes (in grey on the left), and some milestones in the right columns.

See also 1923-06-GA258 and more specifically 1923-06-15-GA258 and 1923-06-15-GA258 where Rudolf Steiner looks back on the three periods of seven years, and speaks about the 21 year rhythm in 1923-06-17-GA258. From the synopsis:

- First period: the development of the basic content of the science of the spirit. View of natural science. The journal Luzifer-Gnosis.

- The second period: exploration of the Gospels, Genesis, the Christian tradition. Expansion of the anthroposophical understanding of Christianity as such. The spread of anthroposophy into the artistic field through performance of the Mystery Dramas in Munich. Reasons which led to the expulsion from the Theosophical Society. Summary of the first two phases. The opposition which grew in strength after construction of the Goetheanum began. Development of eurythmy. The booklet Thoughts in Time of War and the inner opposition which it provoked within the society. The being of Anthroposophia.

- The third phase: fertilization and renewal of the sciences and social relationships. The conditions governing the existence of the Anthroposophical Society. A more open-hearted form had to be found for the three objects of the society: fraternity, comparative study of religions and the study of the spiritual world.

The foundational books

The following books written by Rudolf Steiner can be seen as a foundation for anthroposophy or spiritual science in general:

- 1894-GA004 - Philosophy of Freedom (PoF)

- 1902-GA008 - Christianity As Mystical Fact (and the Mysteries of Antiquity)

- 1904-GA009 - Theosophy (The)

- 1905-GA010 - Knowledge of the Higher Worlds (KHW)

- 1910-GA013 - Outline of Esoteric Science (OES)

Furthermore, another reference book is the compilation of written essays of 1904 later compiled in book form and first published in German in 1939

- 1904 - GA011 - Cosmic Memory (CoM)

.

The important difference with the rest of the GA is that these are works written by Rudolf Steiner as books (to be read and studied (sequentially), whereas the body of lectures covers twenty years of lecturing to the most varied audiences across Europe and these spoken lectures don't always have the accuracy of written works, or may contain errors. More importantly, they do not follow an architectural structure as the books (see eg Schema FMC00.585), as the lecture contents was sometimes dynamically connected 'live' with what lived in the audience.

So in literature one finds references to the three, five, six main books by Rudolf Steiner:

- six refers to the six mentioned above, as in: published books/works

- five to the ones Steiner himself published during his life as books (see also online Five Base Books)

- three refers to the books that provide the essential foundation knowlegde for spiritual science; Theosophy, Outline of Esoteric Science and Knowledge of the Higher Worlds

These books shed light on different matters, or can be seen as entry points into various dimensions of spiritual science:

- 1894-GA004, PoF is the most important philosophical work about Man's epistemology, consciousness and freedom

- 1902-GA008, Christianity as a mystical fact is the base work for The Michaelic stream, see also GA087 with lectures of 1901 and 1902

and then the three main books:

- 1904-GA009, Theosophy is the single most introductory book on spiritual science, providing a view on Man - the human being and Man's bodily principles

- 1905-GA010, KHW is about spiritual development and Initiation (with a section on that also in OES)

- 1910-GA013, OES is the main reference work for matters of Evolution and Spiritual hierarchies, supplemented with Cosmic Memory as a flanker. OES is a study work, Cosmic Memory is a much easier first read to get started.

- 1904 - GA011 - Cosmic Memory is a nice and easy read about the pre-history of humanity before the horizon of current history and science (of approx. 5000-10.000 years), covering the Atlantean epoch and Lemurian epoch

.

Note that in this way, the foundational books map to the logical areas of the Free Man Creator wiki resource - see Schema FMC00.101 and Overview Free Man Creator:

- Man - the human being: Theosophy

- Spiritual hierarchies: OES

- Evolution of the macrocosmos and the microsmos (Man - the human being): OES and CoM

- Initiation: KHW (and OES)

Literature

- Maarten Ploeger : 'Vijf basiswerken van de antroposofie. Een inleiding.' (2025)

Capturing the lectures

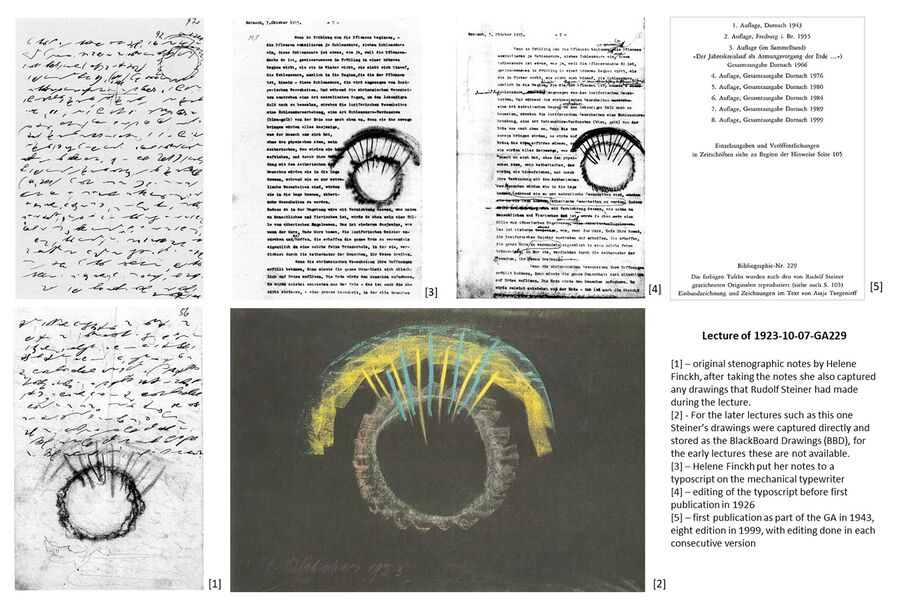

There were five official stenographers, not all professional. Rudolf Steiner was concerned that the texts of the lectures should not be taken as the written word. Not only were the lectures in the spoken word very much tuned to what lived in the audience, but the reflections of these lectures cannot taken verbatim. Furthermore rather heavy editing was applied in the course of decades, where new editors made ever new editions.

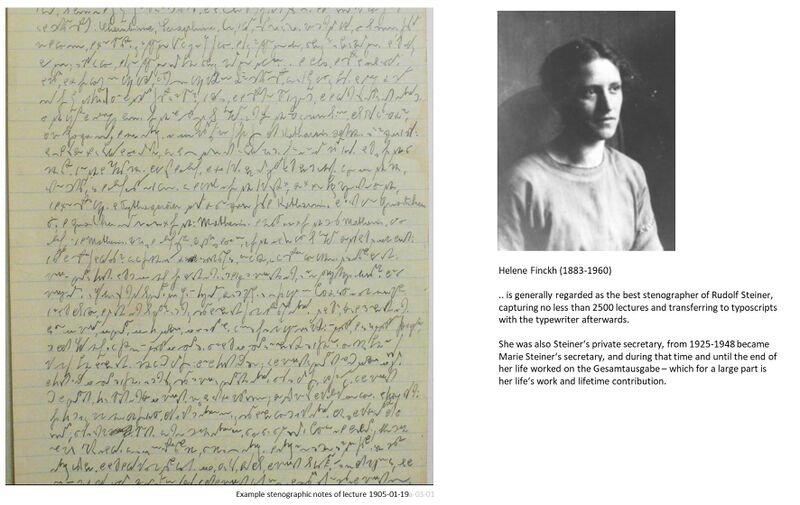

Schema FMC00.340 is an illustration of original stenographic lecture notes, and shows Helene Finckh, (one of, or) the main stenographer(s) of Rudolf Steiner's lectures.

For more info, see also Archivmagazin 12 (Oct 2022): 'Die Stenografin Helene Finckh | Zur Editionspraxis'.

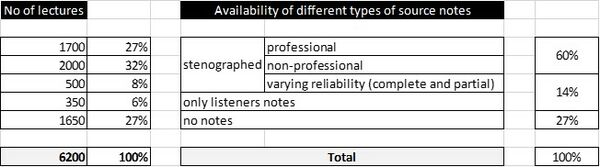

Schema FMC00.120 provides a high level overview of the lectures of which records are available.

Process and positioning

In one century, many hundreds of people worldwide have worked on the GA.

- Starting with the stenographers and transcribers who created the typoscripts at the time of the lectures.

- Then generations of editors that not only produced the lecture texts from all available sources, but also worked on the multiple editions over the decades.

- Then translators from the German originals to the many languages: English, Spanish, Russian, French, Dutch, Portuguese, Italian, ..

- And ultimately publishers.

Not forgetting

- the initiatives by people who scanned and OCR-ed the published text to make them available in digital format on the internet

- the audio versions in German and English.

The GA itself, as we know it today therefore has passed through multiple generations .. just as there have been many generations of people who have worked and maintained it, and are still doing so today.

Schema FMC00.341 illustrates the process from attending the lecture to publication in the GA

Before the GA

Today we live in priviledged times of 'free flow of information' and with digital media and internet technology, the student of spiritual science has instant access to Rudolf Steiner's teachings. One has to realize though that in the first decades, only the first published lecture cycles were available besides the books. Students exchanged, copied, and collected notes also from personal sources whereever they could find them.

- Starting 1923 upto her death in 1948, Marie Steiner's took individual personal ownership of Rudolf Steiner's work to organize the publishing and also own the editorials.

- Adolph Arenson's 1930 listing of the 50 top lecture cycles, see online overview. These cycle numbers were used as lecture reference numbers by anthroposophists before the GA started. So anthro literature upto the 1950-60s will use these cycle numbers. The book 'Leitfaden durch 50 Vortragszyklen Rudolf Steiners' continued to be published until long after the GA, and upto today. The eight edition of 1984 (1000+ pages) contains an introduction of how this initiative came into being after thorough preparatory talks with Rudolf Steiner, and in-depth work between Feb-1918 and May-1925.

- Leading thoughts. Rudolf Steiner's own initiative to provide a 'dashboard' overview to the contents of his work, arose with the compilation of 185 Leitsätze or Leading Thoughts published as 1925-GA026, see Anthroposophical Leading Thoughts. Regarding In Newsletter to members Nr 31 in 1924, Rudolf Steiner wrote (freely translated here):

For more info see Carl Unger (1878-1929): 'The language of the consciousness soul - A guide to Rudolf Steiner's Leading Thoughts' (2012 in EN, original 1930 in DE 'Aus der Sprache der Bewusstseinsseele: Unter Zugrundelegung der Leitsätze Rudolf Steiners').. the work that is made available in the printed lectures and cycles should not all to be readily be underestimated By reading together and integrating all that can be found separated in these individual lectures and cycles, one can find back the perspectives from which is spoken in the Leading Thoughts.

- Schmidt and Mottelli: before the (Gesamtausgabe) or CW (Collected Works) became established, lectures were often referenced by the Schmidt number - see item four in Schema FMC00.039. Hans Schmidt gave each lecture a unique number, similar to how this is done in music (eg for Mozart the KV numbers allocated by Köchel (K) or the BWV numbers for Bach's Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis). For decades, the works by Schmidt and Mottelli (from the 1970s and early 80s) were the most complete references that were published and available to students.

When studying secondary anthroposophical literature, therefore, one will find that for example Maximilian Rebholz (publishing in the period 1930-1950) referenced the Arenson cycle numbers, Ernst Hagemann (publishing in the 1970s) used the Schmidt lecture numbers.

- As the GA became established, it became common practice to use the GA volume number and lecture date, the format also used on this site, see more on: RSL references. Today the Arenson cycle numbers and Schmidt lecture numbers are hardly used anymore.

The GA idea, plan and project initiative

- First ideas from Ehrenfried Pfeiffer in 1947 and first proposal in 1953 by Teichert and Picht

- Foundational plan for editorial work and publications by Hella Wiesberger in 1961, updated in 1984 (PDF available in references below)

- Though it was officially established as a publishing initiative in 1961, the first actual releases began in 1957,

Roll-out of publications

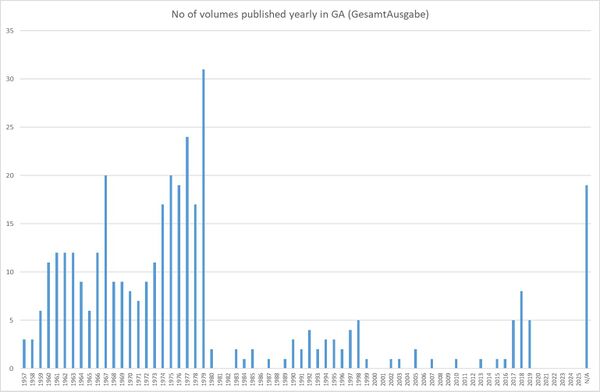

Schema FMC00.072 below shows the number of GA volumes published per year. Upto 1980 the data is based on Mottelli, afterwards no exact data was available. Since the GA2025 the data is again available.

It shows that in the period 1960-1980 (both years inclusive), a yearly average of 13 volumes per year was published for a total of 277 volumes in those 21 years and for a total of 289 volumes in 1980. This of course was able to build on the large volume of material that had been published in the fifty years from say 1910 to 1960, now fitting al the available publications after re-editing and bundling into the new GA framework.

Although no exact data are available for the period afterwards, it's clear that the pace dropped afterwards in the period 1980 to 2010.

Existing volumes were revised and updated regularly with consecutive editions.

Amazingly, key materials only got published very late, examples are GA089 (2001), GA090 (2017) and GA091 (2018!).

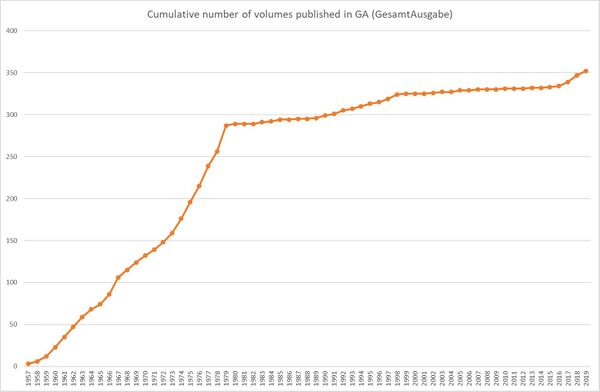

Schema FMC00.073 shows the cumulative number of volumes in the published GA

The GA2025 initiative

The volume of Rudolf Steiner's work is so large that even after one century not everything has been published.

In 2015-16, therefore, an initiative was started to finish the publications in one last decade by 2025, 100 years after Rudolf Steiner's death. In the years 2016 to current 2025, previously unpublished materials thereby became available. Whereas some volumes contain different lecture versions of materials already available via other lectures published before (still interesting for the student because of nuances and details), some volumes contained important key materials that are essential for a complete picture in certain areas of study.

Examples of important volumes are a.o. GA90A, GA90B and GA091 published in 2018, or GA244 published in 2022, GA265A published in 2024.

For more info see Schema FMC00.072A below and the GA2025 public web page.

Schema FMC00.072A: provides an overview of the GA2025 initiative and the status of volumes of Rudolf Steiner's Gesamtausgabe (GA) published in the decade 2016-2025.

Flanker materials

Indexes and lexicons

Indexes and Lexicons: Navigating anthroposophical resources#Indexes and Lexicons

Contributions to the GA from Rudolf Steiner Verlag

in German: 'Beiträge zur Rudolf Steiner Gesamtausgabe; published by Rudolf Steiner Verlag

for an overview and downloads, see: en.anthro.wiki/Contributions_to_Rudolf_Steiner%27s_Collected_Works

Study companions to GA volumes

Study companions: see: Navigating anthroposophical resources#Note 1 - Study companions for GA volumes

Critical edition

The GA complete edition was not conceived as a historical-critical text edition, but as a reading edition for study. A text-critical edition of the main works exists in which textual development and variants, historical references and and literary source etc., are indicated in an academic way. This edition was developed in the period 2013-2025, with Christian Clement as main editor, and is published by Fromman-Holzboog Verlag. See more on www.steinerkritischeausgabe.com/

Notes

- the fact that this edition is published by Christian Clement has sparked a lot of response (as a reader writes: "also negative down to hatred. Clement works at the Mormon University in Utah, and this edition has been denounced by some as a Mormon edition" because of its critical academic review dimension)

- underlying the debates on the 'critical editions' regarding its value add and actual intentions, seems to be the fact that a critical edition based or inspired on the contemporary mineral worldview and its academic processes is not able to truly grasp or comment with understanding what Rudolf Steiner sketches as complex spiritual scientific explanations (eg if the text is purely parsed literally without holistic insight). More on this on Spiritual science#3/ the scientific approach.

- irrespective of any judgment here, at least the extremely complicated editorial history of GA is presented in an exhaustive and correct manner.

Critique on the Gesamtausgabe

The publishing of Rudolf Steiner's complete works is a tremendous undertaking that has spanned over 100 years, and this naturally comes with obvious implications, the two main ones being:

- - the fact that generations of editors have changed the original texts based on their own standards, judgment (of what phrasing to use from which lecture notes and typoscripts and previous editions) and (by necessity, and with all respect) limited understanding of the whole of anthroposophy, thereby getting further away from the original lecture texts. (Note: this is not even taking into account the cumulative effect of translators, so this point is meant for the German version).

- - the fact that much remained unpublished, 'hidden' or 'locked up' in the archives in Dornach for decades. See Schema FMC00.072 and Schema FMC00.073, and the GA2025 initiative started in 2016 to finalize publication of all that was left unpublished before 2025 (Schema FMC00.072A).

Both elements have given rise to healthy critique and additional initiatives that can only be seen as enriching the whole. Some of these are mentioned in this section.

Note from experience:

1 - In many cases, the earnest student can get great benefits of having multiple original source material texts available instead of just the say ninth edited German version that was then translated to English. Indeed editors need to make choices if different source texts have slightly different wordings, or some contain certain sentences or phrasing and others do not. But clearly there is a great advantage of being able to go back to the originals for certain sentences or paragraphs of key lectures, and be able to study all that is available to get closer to an understanding (than what is possible with an english translation of say the ninth edited official german edition that was published).

2 - Examples on this site of schemas that document source research (not exhaustive), as generations of editors and translators have made (no doubt good-intended) changes and thereby changed the text in important ways: FMC00.372, FMC00.381, FMC00.468A, FMC00.001A.

Examples taken from: FMC study schemas#Introductory overview

The Uranos and Steinerdatenbank initiative

As mentioned above, the official version of Rudolf Steiner's Gesamtausgabe left certain groups of students with two main concerns, issues or frustrations:

- the many editing iterations have caused changes versus the original lecture contents, as generations of editors made changes for various reasons (maybe readability, logical flow, interpretative clarity). However, the original manuscripts of stenographers and typoscripts were only available in the Dornach archive.

- many lectures remained unpublished and were so to speak 'locked up in Dornach' and not available for the community of students of anthroposophical spiritual science worldwide. This stagnation can be seen in Schema FMC00.072, see situation after years 1980 and 2000.

Therefore a group of people set out on an huge endeavor to go to Dornach and systematically photograph the originals and make these digitally available online for the public in a database. This huge pioneering work had the great advantage of making available all the original hand written notes and typoscripts, also for unpublished lectures.

At the same time original study notes had been gathered from deceased first generation anthroposophists, and part of this huge volume of materials was digitized and would later be shared via the Uranos archive..

Key individuals in these efforts of making Rudolf Steiner's heritage more broadly accessible were Thierry Cassegrain, Michael Schmidt (1968-), Ole Blente, Rudolf Saacke (Freie Verwaltung des Nachlasses Rudolf Steiners), and Günter Kreidl (Uranos e.V.) (1940-2022).

Their initiatives brought up internet servers that hosted a number of key sites, a.o. fvn-rs.net, steiner-klartext.net, and the truly unique steinerdatenbank.de developed by Michael Schmidt. This database was certainly the most advanced online resource for Rudolf Steiner's lectures in terms of design, development and efficiency.

Unfortunately both these unique sites, uranosarchiv.de and steinerdatenbank.de went offline in the period 2022-2023. The old site 'www.steiner-klartext.net' seems meanwhile to have been restored.

note: part of this story is touched on (though just a few pages) in the book by Thierry Cornbrecher: 'Die Abenteuer des Thierry Cornbrecher: Autobiographie und rote Pfade eines Suchenden' (2016) that exists in DE and FR languages.

Alternative publishing

Rudolf Steiner Ausgaben (Pietro Archiati)

This publisher was started on the initiative of Pietro Archiati (1944-2022) who discovered the work of Rudolf Steiner in 1997. Later he said: “Within days ... I knew with innermost certainty: this is what you have been searching for your whole life in East and West. It had the effect of a hurricane on me.”

From 2004 until his death, he collaborated with publisher Monika Grimm at Rudolf Steiner Ausgaben to publish works and lectures by Rudolf Steiner that are particularly relevant today.

This publishing house offers truly unique volumes much worthwhile for comparative study, from the website www.rudolfsteinerausgaben.com:

The Rudolf Steiner Complete Edition (GA) contains Rudolf Steiner's lectures in the version originally compiled by Marie Steiner and her colleagues. The target audience was primarily theosophists and later anthroposophists, whose needs were given priority. Over the course of the last century, a new situation has arisen:

- On the one hand, there was a need to make Rudolf Steiner's ideas accessible to as wide an audience as possible,

- while on the other hand, scientific requirements in terms of accuracy have become more stringent.

The plain text transcripts in the Goetheanum archives have recently been made public. Among them are many valuable, partly handwritten plain text transcripts that are much closer to Rudolf Steiner's spoken words than the wording in the GA. This also explains why quite a few people find the text of the GA difficult to understand.

In recent years, an intensive comparative study has been undertaken to determine which transcripts are closer to Rudolf Steiner's spoken words. It often happens that there are two versions of a lecture, a shorter and a longer one, where it is clear that the longer one is only an editorial extension of the shorter one (e.g., because it adds nothing new in terms of content or contains anything that distorts the meaning). The text in the GA usually contains the longer version.

...

Typical examples illustrating the difference to the GA can be found here.

For the 'Rudolf Steiner editions' it is not important that the reader comes to the same conclusion as them with regard to different versions of a lecture. What is important is to give the reader the opportunity to form their own opinion. This is achieved through text comparisons and unrestricted access to all documents that the publisher has at their disposal. The respective sources are listed in each volume under the heading “About this edition.”

Nine examples are given on this page with extracts, including key lectures on the Christ and the Mystery of Golgotha, and the GA173 volume.

That is why on this site, we refer to some of the volumes, eg here: Guided study approach to Christ#Step 1: the two central lectures

Individual contributions - a few profiles

Certain individuals have played a key role in the process, others stood out for special reasons. There are too many to mention, but some examples to illustrate (section to be completed):

- Marie Steiner and Hella Wiesberger: instrumental in realizing the Gesamtausgabe

- Helene Finckh (stenographer)

- Anna Meuss (translator to English)

Various more

Rudolf Steiner's work as a painter

- Rudolf Halfen and Walter Kugler (editors): 'Das malerische Werk' (Mit Erläuterungen und einem dokumentarischen Anhang (2007)

- Reproduktionen aus dem malerischen Werk von Rudolf Steiner

- Naturstimmungen: Neun Schulungsskizzen für Maler. Pastelle 1922

The English version

History and the first translations

Stories from the very early days ... still to be added here.

The rsarchive initiative

See background and history here: Navigating anthroposophical resources#Note 2 - information about the RSarchive

The Collected Works initiative

Since 2006, SteinerBooks (Anthroposophic Press, US) and Rudolf Steiner Press (UK) have been publishing a volume-by-volume English translation of the GA. An estimated 100 works are available.

.However there are other publishers of anthroposophical works in English:

- Temple Lodge Publishing (UK): https://www.templelodge.com/

- Floris Books (UK): https://www.florisbooks.co.uk/

others: Anastasia, Mercury Press, Adonis Press, Completion Press

Practical tips

This section gives some practical tips for students working in English, ao how to get hold of old translations, use of the audio versions, etc

- Take care to trust only one available version if your study goes deep into something where you base yourself upon one lecture.

- In some cases the version on rsarchive is incomplete or even erroneous (eg 1906-07-29-GA097 on Wagner and blood at the MoG, or the GA215 cycle), or with terrible old translations. You will find the same if you listen to the audio versions, and then go to look for quotes or sections in the rsarchive.

- If multiple versions are available, parse more than one.

- From personal experience .. it is interesting to purchase previous older book versions to get versions of lectures not available on rsarchive, or just better translations. With contemporary tools it is now much easier to scan and OCR these to have a text file for personal study - allowing parsing and annotation. The rsarchive is a wonderful and unique tool, use it but make sure not to stop there.

- By extension, one can use tools like booklooker.de to find German publications (especially secondary literature) and apply the same process: scan + OCR + machine translation tool. Tools such as deeplwill convert the whole documentso one has a draft work document in English to use for personal study. Of course this assumes one has knowledge of German too, to be able to check the German original as part of the study process.

The audio version

English

The pioneer of this effort was Rick Mansell who (translated and) read-to-tape some 1900 lectures of Rudolf Steiner between 1939-1981. These are still available from The Rosenkreutz Institute in the US (payable)

Dale Brunsvold started his reading and recording efforts in 1980's. Since 2005 these materials, over 2000 files and over 1200 hours of reading time, are freely available and downloadeable from his website rudolfsteineraudio.com

German

Some paid versions like: www.rudolf-steiner-audio.de/

The GA in other languages

According to the Steiner International Publications Index, the German GA has been translated into 29 languages, including:

- central European: Dutch, English, French

- northern European: Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, Swedish

- southern European: Catalan, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish

- eastern European and eastward: Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Estonian, Georgian, Hungarian, Polish, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Ukrainian

- other: Arabic, Chinese, Hebrew, Japanese, Korean, Tagalog, Turkish

.

The languages highlighted in bold are in the top 10 of most spoken/read languaged worldwide.

2025-06-12 - Henry Holland

Thoughts from Henry Holland, translator and co-organizer of the ‘100 Years Rudolf Steiner’ conference at Harvard University.

Translated from: dasgoetheanum.com/anthroposophie-multilingual/

Although they are hardly mentioned in the history of anthroposophy, translations of Steiner's writings and lectures into numerous languages were indispensable for the global growth of this originally very small movement. The conference at Harvard, which takes place from December 14 to 16, would never have the same appeal without these translations. Around 100 people from very diverse national, linguistic, and social backgrounds have submitted contributions. Among them are people of color who want to talk about the issue of racism. Most of these people do not read German.

UNESCO's Index Translationum – the first census of translated works worldwide – shows that Steiner was the third most translated German-language author between 1979 and 2009. He was only behind Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm, and even ahead of Freud, Nietzsche, and Marx.

In German-speaking academic circles, the overall quality of English translations has recently been criticized, leading to the conclusion that serious anthroposophical research must be reserved for those who can read German. But don't biodynamic farmers in Peru, for example, some of whom have expressed great interest in the Harvard conference, make a significant contribution to research on anthroposophical principles in their daily work? Instead of blanket condemnation, it might be interesting to take a look at English-speaking protagonists who are currently concerned with the quality of translations. Thomas O'Keefe of Chadwick Library Press deserves attention for the new and carefully revised translations he has supervised. The new English-language Steiner biography that religious scholar Aaron French and I are currently writing also contains new translations of Steiner's words – and a critical examination of this fascinating figure in cultural and intellectual history, about whom ignorance and polemics still prevail.

.

Availability of Rudolf Steiner's work in some of the main languages worldwide besides German and English:

Spanish

XL or PDF file here

French

XL or PDF file here

Portuguese

XL or PDF file here

Russian

XL or PDF file here

Dutch

XL or PDF file here

Problems with using the GA

The current Gesamtausgabe is a absolute reference foundation, yet like anything it comes with trade-offs of choices made. The student or spiritual science needs to be aware of certain practical aspects of the materials and tools used as the individual soul work of the student as a human being is central.

Some illustrations are for example:

- the fact that the GA volume segmentation does not respect chronology or context (whereas Rudolf Steiner sometimes continued on a theme covered days before, these puzzle pieces are now scattered across volumes)

- in consecutive editions of the GA volumes, individual lectures were moved in out and between volumes. This sometimes makes it difficult to trace or uniquely define a lecture.

This problematic is covered more extensively on: Problem statement regarding the study of spiritual science

And related, see also:

The Blackboard Drawings and original illustrations

Whereas Rudolf Steiner had been using the blackboard for illustrations in his lectures before, only around 1919 and up to 1924 did Steiner’s assistants (especially Emma Stolle and Helene Finckh) began placing sheets of black paper on the blackboards before lectures so the chalk would remain on the paper afterward.

These sheets were kept after the lectures and were stored in the archives of the Goetheanum, but there was no systematic effort to preserve them until the 1950s when the Rudolf Steiner Nachlassverwaltung (Rudolf Steiner Estate Administration) began systematically sorting, conserving, and photographing the blackboard drawings and link them with the corresponding lectures in the Gesamtausgabe.

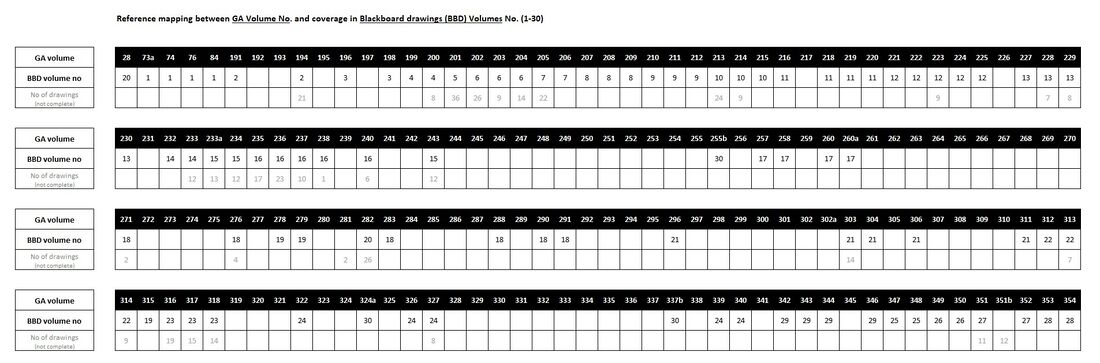

FMC00.342 shows that over a thousand of Rudolf Steiner's blackboard drawings (BBD) have been published and are available in thirty volumes.

The GA volume mapping cross-reference is available high level in Schema FMC00.342B.

For more info, see:

- Martina Maria Sam: Bildspuren der Imaginations - Rudolf Steiners Tafelzeichnungen als Denkbilder (2000)

- as a quick reference, hereby a partial index: Digital RSL BlackBoard Drawings - index only

FMC00.342A provides illustrations from various exhibitions of Rudolf Steiner's Blackboard Drawings (BBD).

FMC00.342B provides a quick reference table with the mapping of what original BBD drawings by Rudolf Steiner are available in the 30 volumes of the official publications.

For those that are not covered, only the drawings are available of people who attended the lectures and copied the drawing from the blackboard. These are available on steinerdatenbank.

The Notebooks

Introduction

Rudolf Steiner left approx. 600 notebooks with entries on which he comments himself below. Only some of these have been published as part of the GA volumes, the notebooks have not been published themselves, only one book exists which is hard to find, see references below.

These notebook entries may be cryptic, but some can provide breakthrough clues, some examples:

- Walter Cloos found a key clue in a notebook entry, that allowed him to put all the puzzle pieces of his understanding together, as he explains in his book 'The Living Earth', see Mineral kingdom page. The book uses the few densely written phrases of the notebook entry as a leitmotiv for the whole book and the many chapters structured around it.

- Schema FMC00.326 on the Kundalini page

- Christ Module 9: Trinity and Logoi#Note 5 - Christ, the cosmic I, and relation to the spiritual hierarchies

Reference extracts

Rudolf Steiner mentioned in lectures how the notebooks came into being, and what they contained.

Below are some quotes (not exhaustive) as illustrations. The first lecture where Steiner fully explains the process is 1923-04-30-GA084, this is repeated again later in a similar way in 1923-05-14-GA080B and 1923-09-29-GA084.

1923-04-09-GA084

computer translation

I have the habit of always writing down or formulating with a pencil in my hand everything that comes to me from the spiritual world, either in words or in some kind of drawing. As a result, I have many cartloads of notebooks.

original in DE

Ich habe im Gebrauche, eigentlich alles das, was sich mir ergibt aus der geistigen Welt, immer mit dem Stift in der Hand aufzuschreiben, zu formulieren, entweder in Worten oder in irgendwelchen Zeichnungen. Dadurch ist die Anzahl meiner Notizbücher viele Wagenladungen

1923-04-30-GA084

The path I am describing to you, in order to arrive at an understanding of the human being by going beyond mysticism and natural science, is not one that can be dismissed by casually labeling it 'clairvoyant'. This is a path in which one knows how each step follows the previous one, just as the mathematician knows how one mathematical derivation follows another. The path that I have been able to sketch for you – with reference to the books mentioned – is the path of anthroposophy, the path that leads to the unborn and immortal nature of the human soul in a way that could be explained to a strict mathematician, and which shows how one does not have to stop at the world in order to penetrate into the human being, as one does not have to stop at the human being in mysticism in order to penetrate into the world, but how one can connect the knowledge of the world with the knowledge of the human being. If enough natural science and enough mysticism is pursued in this way, then the possibility will arise for the future spiritual civilization of humanity to fulfill the word that approaches man so powerfully admonishing, the word “know thyself!”

Such knowledge as I have just described, however, differs from the knowledge that is bound to the nervous system, which is essentially knowledge of the head.

And allow me to make a personal remark, which is, however, completely factual. As a spiritual researcher trying to penetrate this realm, which I call the realms that one has to pass through before birth and after death, one is aware that you cannot get by with the thinking that otherwise serves you in life. You have to develop a strengthened thinking that engages the whole person. One does not become a medium through this, but the whole human being must be taken up by such thinking. Such thinking penetrates into feeling, into emotion, and even demands that the human being surrender himself to it with the whole content of his will. At the same time, thinking about spiritual content is such that it cannot be incorporated into the memory in the usual way, like any other.

Here too I would like to make a personal comment: You see, when a spiritual researcher gives a lecture like the one I am giving here, he cannot prepare it in the same way as other scientific lectures. In that case he would only appeal to memory.

But what has come about through such a deepening cannot be assimilated by memory, it must be experienced again and again in every moment. It can be brought down into those regions where we put our knowledge into words, but one must endeavor to do so with one's whole being.

And that is why I have a profound experience of only being able to incorporate into human language that which I succeed in researching in the spiritual world. And by incorporating it into human language, it also becomes incorporated into memory; I only succeed when I draw or write down a few lines, so that not only the head but also all the other organ systems are involved.

You have to feel the need to take one or the other to help you, because you can't manage it, it fluctuates when you want to grasp it with your head. The important thing is that I express the thought with lines and thus fix it.

So you can find whole truckloads of old notebooks of mine that I never look at again. They are not there for that either, but so that what I have laboriously extracted from my mind can be developed to the point where it can be clothed in words and thus brought to the memory.

Once it has been written, one has participated in the spiritual production with something else in one's organism than merely with the head, with thoughts, then one is able to hold on to that which wants to escape. The rest of the human organization is initially uninvolved, unconsciously more dormant than the mental processes, and when we incorporate something into our will, we make use of those organs that are in a state that we describe as dormant when we are awake. We are actually only awake in our thoughts and imagination, for the way in which our mental images penetrate into our organism as a volitional decision, to become a movement of the hand or fingers, remains completely shrouded in darkness in ordinary consciousness. Only the spiritual researcher will recognize what happens between the process in the brain and the movement. And so spiritual knowledge, which is not ordinary head knowledge, is entrusted to the whole human organization. By acquiring knowledge of the human being from within the whole human being, one is able to apply this knowledge of the human being, which can take the prenatal and the after-death as a tangible reality, to practical life in a completely different way than one would be able to without this true knowledge of the human being.

1923-05-14-GA080B

Hence, allow me in conclusion to say something personal by way of illustration, although this is not meant to be personal, but is meant rather to be entirely objective.

If you really want to capture that which is disclosed by the spiritual world, you need presence of mind, because it slips so to speak, turns away quickly; it is fleeting. That which is to a certain extent advanced through an improvement in the power of memory imprints itself only with difficulty upon the ordinary memory. One must use all of his strength to bring down what he beholds in the spiritual world, to bring this down to ordinary language, to ordinary memory-thought.

I would not be able to lecture about these things if I did not try by all means to bring down what arises in me of what can be beheld in the spiritual world, especially to really bring these thought-words down into physically audible regions. One cannot comprehend with the mere head, because the entire human being must to a certain extent become a sense organ, but a spiritually developed sense organ.

Therefore I attempt every time — it is my custom, another has another one — I attempt every time if something is given to me from the spiritual world, not merely to think it through as I receive it from the spiritual world, but to write it down as well, or to record it with some characteristic stroke, so that the arms and hands are involved as well as the soul organs. So something else other than the mere head, which remains only in abstract ideas, must be involved in these findings: the entire person.

I have in this way entire truckloads of fully-written notebooks that I never again look at, which are only there in order to be descriptions, in order to provide preliminary work in the physical world for that which is from the spiritual world, so that the spiritually beheld world can then really be clothed in words; whereby the thoughts of which memories are usually formed or that usually apply in life can actually be penetrated — Thus one obtains a science that relates to the whole person.

1923-09-29-GA084

In order to render it clear that super-sensible knowledge cannot really be a mere head-knowledge, but lays hold upon the human being in a vastly more living and intense way than head-knowledge, I should like to mention the following. Whoever is accustomed to a living participation in ordinary knowledge — as every true super-sensible knower should really be — knows that the head participates in this ordinary knowledge. If he then ascends, especially if he has been active through his entire life in the ordinary knowledge, to super-sensible knowledge, the situation becomes such that he must exert all his powers in order to keep firm hold upon this super-sensible knowledge which comes upon him, which manifests itself to him. He observes that the power by means of which one holds fast to an idea about nature, to a law of nature, to the course of an experiment or of a clinical observation, is very slight in comparison with the inner force of soul which must be unfolded in order to hold fast to the perception of a super-sensible being.

And here I have always found it necessary not only, so to speak, to employ the head in order to hold firmly to these items of super-sensible knowledge, but to support the force which the head can employ by means of other organs — for example by means of the hand. If we sketch in a few strokes something that we have reached through super-sensible research, if we fix it in brief characteristic sentences or even in mere words, then this thing — which we have brought into existence not merely by means of a force evoked through the nerve system applied in ordinary cognition, but have brought into existence by means of a force drawing upon a wide expanse of the organism as a support for our cognition, — this thing becomes something which produces the result that we possess these items of super-sensible knowledge not as something momentary, that they do not fall away from us like dreams, but that we are able to retain them.

I may disclose to you, therefore, that I really find it necessary to work in general always in this way, and that I have thus produced wagon-loads of notebooks in my lifetime which I have never again looked into. For the necessary thing here lies in the activity; and the result of the activity is that one retains in spirit what has sought to manifest itself, not that one must read these notes again. Obviously, this writing or sketching is nothing automatic, mediumistic, but just as conscious as that which one employs in connection with scientific work or any other kind of work. And its only reason for existence lies in the fact that what presses upon us in the form of super-sensible knowledge must be grasped with one's whole being. But the result of this is that it affects, in turn, the whole human being, grasps the whole person, is not limited to an impression upon the head, goes further to produce impressions upon the whole human life in heart and mind.

Illustrations

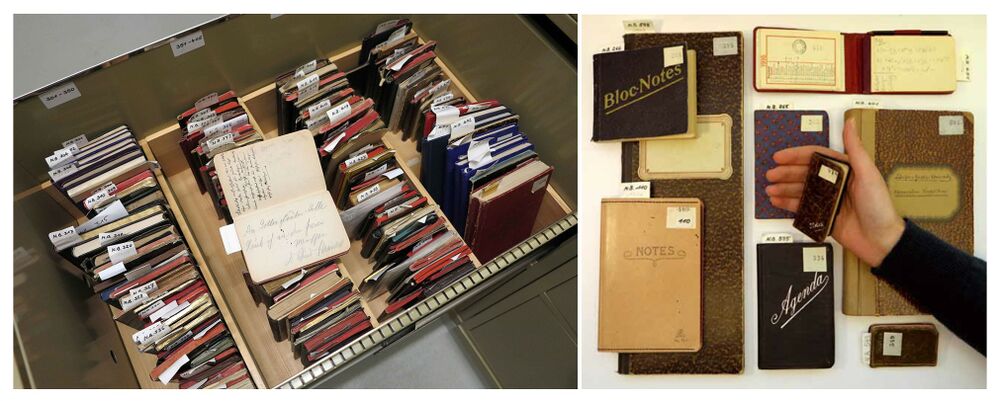

FMC00.339 shows the Rudolf Steiner's notebooks in the archive in Dornach

FMC00.339A shows some illustrative examples of notebook entries.

Discussion

Note 1 - Size of the GA or CW

Rudolf Steiner's Gesamtausgabe (GA), or Collected Works (CW), consists of a vast body of texts, including lectures, books, essays, and letters. The total number of pages varies depending on the edition and publication format. Generally, the complete works encompass around 354 volumes, with each volume typically ranging from 200 to 500 pages (for extensive scholarly and philosophical writings).

- On this site the figure 100.000 pages is mentioned as a purely indicative high level figure, this does not represent an exact figure.

- To estimate the total number of pages, we can take an average page count per volume and multiply it by the total number of volumes. Assuming an average of 350 pages per volume, one could estimate 354 volumes x 350 pages/volume for approx. 123.900 pages. Of course this estimate is very rough, as some volumes do not consist of text but are more graphical, eg BBD, paintings, notebooks.

- A figure often read and used is 86.000 pages.

- chatgpt 2025 approaches it as follows

- Volumes: GA numbers run a little beyond 360 volumes (GA 1 – GA 354 + supplements, indexes, and special editions).

- Pages: average volume between 300–500 pages, though some lecture cycles are smaller (~150–200 pages) and some large collections exceed 700–900 pages.

- A conservative mean would be ~400 pages × ~360 volumes = ≈ 140.000 pages.

- Including indexes, supplements, etc the Gesamtausgabe is expected to surpass 150.000 printed pages when complete.

Related pages

- Tools and practical site info

- Navigating anthroposophical resources

- Individuality of Rudolf Steiner

- Navigating anthroposophical resources#Note 1 - Study companions for GA volumes

References and further reading

- Wolfram Groddeck: 'Eine Wegleitung durch die Rudolf Steiner Gesamtausgabe' (1979)

- Hella Wiesberger and Emil Mötteli: 'Bibliographische Übersicht, Das literarische und künstlerische Werk von Rudolf Steiner'(1984)

- Archivmagazin

- Die Rudolf Steiner Gesamtausgabe: Aktueller Stand und Abschlussplanung - Archivmagazin Nr 5 Aug 2016

- Michael Schweizer: 'Zur Qualität der stenografischen Mitschriften von Rudolf Steiners Vorträgen' - Archivmagazin Nr 6 Jun 2017

- Rudolf Steiner Archiv

- Martina Maria Sam: Bildspuren der Imaginations - Rudolf Steiners Tafelzeichnungen als Denkbilder (2000)

- The notebooks of Rudolf Steiner, edited by Etsuko Watari and Walter Kugler, Watari Museum of contemporary art (Tokyo), (2000)

- Wolfgang Gädeke, Christward Kröner: 'Wortgetreu und unverfälscht? Haben wir in der Gesamtausgabe Texte Rudolf Steiners?' (Flensburger Hefte, 2002) (Kritik an der Editionspraxis der Rudolf-Steiner-Nachlaßverwaltung)

- Irene Diet:

- 'Das Geheimnis der Sprache Rudolf Steiners. Vom ungelösten Rätsel des Verstehens' (2011)

- 'Ist die «Rudolf Steiner Gesamtausgabe» das Werk Rudolf Steiners? Eine historische Studie' (2013)

- 'Welches Recht hat Rudolf Steiner selbst an seinem Werk? Anmerkungen zum Projekt des Rudolf Steiner Archivs, bis 2025 die Gesamtausgabe abzuschließen' (2016)

- Friedwart Husemann: 'Rudolf Steiners Schriften: in 50 kurzen Porträts' (2018)