Virtues

Moral ideals and impulses in Man are described through the seven virtues, whereby can be distinguished the four great platonic virtues (justice, wisdom, courage and temperance), and the three highest values of Faith, Love and Hope.

The forces of morality or moral impulses that enter the body through the head encounter and meet the forces of the I in the blood (see 1916-08-05-GA170 on Human 'I', FMC00.261 below, and see also I-organization).

From a spiritual scientific perspective, there is a major distinction between the pure concepts that are described with virtues (eg words like 'good', or 'love'), and our current human intellectual knowledge about any such word as a concept with related meaning, as well as the actual reality of ourcurrent human faculty of living this quality. These are quite different from the absolute spiritual or divine quality. (Beinsa Douno 1926-01-17)

Aspects

Main seven virtues

- moral progress and virtues as central in initiation: in initiation exercises, one works the virtues by self-assessment of character treats and their transformation (as "progress in spiritual training is not thinkable without a corresponding moral progress" (1909-GA013 Ch. 5)); many books support this process and provide frameworks (of up to hundreds) of character treats and virtues; see Initiation exercises#Elemental balance - character transformation

Four platonic virtues

- the four platonic virtues: justice, wisdom, courage and temperance - see Schema FMC00.261A for an overview of key lectures

- justice and wisdom point to past, courage and temperance to future incarnations (1915-01-31-GA159)

- relationship with bodily subsystems and organs: wisdom-head, courage-breast, temperance-abdomen and justice: the 'invisible' whole physical body (1916-08-07-GA170)

Faith - Love - Hope

- the three highest virtues of Faith, Love and Hope (FLH)

- bring about the transformation of Man's astral body, etheric body, and physical body respectively into the spirit-self, life-spirit, and spirit-human (1911-06-14-GA127 and Discussion note).

- "The inmost kernel of our being may be said to be sheathed in our faith-body or astral body, in our body of love or etheric body, and in our hope-body or physical body" (1911-12-03-GA130)

- "the 'faith-body' throws its reflection on to the human soul, in this fifth epoch. Thus it is a feature of present-day man that he has something in his soul which is, as it were, a reflection of the nature of faith of the astral body. In the next sixth cultural age there will be a reflection within Man of the love-nature of the etheric body, and in the seventh age, before the great catastrophe, the reflection of the nature of hope of the physical body." (1911-12-03-GA130)

- Faith

- for Soloviev, faith is both a necessity and a morally free act: Faith; in so far as it relates to Christ, is an act of necessity, of inner duty. We have a duty to believe in Christ, for otherwise we paralyse ourselves and give the lie to our existence. Faith is allotted everything that makes up Man's relationship to what is divine and spiritual. (1911-10-07-GA131, 1922-01-07-GA210)

- faith had a different meaning at the time of the Christ and the Gospels as it has today. then with Faith was meant an active force accomplishes something .. not simply evoke an idea or to awaken knowledge (as is how the word is used today). (1917-04-10-GA175; see Christ Module 13 – Teachings through the ages#1917-04-10-GA175)

- for love, see the Love topic page

- bring about the transformation of Man's astral body, etheric body, and physical body respectively into the spirit-self, life-spirit, and spirit-human (1911-06-14-GA127 and Discussion note).

Various other

- see also the link with

- the moral nature of the ether, see Spectrum of elements and ethers

- the spiritual nature of the consciousness soul, see Human character - the I and threefold soul#Note 2 - On the consciousness soul

- spiritual science and the quest for understanding of world evolution, from this search for wisdom goodness and virtue is born in the human heart, "the child of wisdom will be love". (1912-01-01-GA134, see Christ Module 15 - Study of Spiritual Science #Inspirational quotes)

- developing virtues through art (see eg 2006 book by Lutters, re: Art#Seven (liberal) arts)

seven vices or sins

- seven vices or seven (deadly) sins in Christianity: pride, envy, anger/wrath, sloth/dejection, avarice/greed, gluttony, lust

- sources: Tertulian, Evagrius Ponticus, Gregory the Great, Thomas Aquinas, Dante’s Divine Comedy

- see wikipedia page for seven sins

- notes:

- avarice tends to refer to wealth and money; greed is more sensual, associated with overconsumption

- depiction in art

- examples:

- The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (attributed to Bosch or a follower)

- The Seven Vices: Wrath (fresco by Giotto in Cappella Scrovegni (Padua, Italy)

- the seven deadly sins also appear symbolized in digital games (see Frank Bosman paper under Further reading below)

- examples:

Terminology

- the virtues are used widely over many centuries and even millenia in esoteric, theological, alchemical texts. This lists some examples of other words or terms used (sources a.o. Beinsa Douno, text 'The Chrysopee of the Lord'). There is apparantly a mixture of the four and three main virtues listed above, with wisdom-beauty-strength and/or truth-beauty-good.

- five Christian virtues: love, wisdom, truth, justice, and virtue

- four cardinal virtues: force, prudence, temperance and justice.

- three theological virtues : faith, hope and charity (instead of love)

- supreme dyad: intelligence and wisdom

- other listings: faith, hope, charity, fortitude, justice, prudence, temperance.

Truth Beauty Good

- see Truth Beauty Good also for link with Wisdom, Beauty (piety, goodness) and Strength

Initiation

- moral progress and virtues: in initiation exercises, one works the virtues by self-assessment of character treats and their transformation (as "progress in spiritual training is not thinkable without a corresponding moral progress" (1909-GA013 Ch. 5)); many books support this process and provide frameworks (of up to hundreds) of character treats and virtues; see Initiation exercises#Elemental balance - character transformation

Conscience

- our dignity as human beings is inseparable from conscience, which we have because of our human 'I', it is the voice of our inner life that enables us to determine our direction and our goal (1910-05-05-GA059)

- conscience is an remnant in our soul we are not aware of consciously, of our connection with spiritual beings of the higher hierarchies, that developed when we felt ourselves in the company of the beings of the higher hierarchies before descent to Earth stage (and the development of our current waking consciousness) (1916-08-27-GA170)

- conscience arose in human history in the Greco-Latin cultural age

- "the concept and word 'conscience' is something which was only known after a certain point of time in Greek history." It cannot be found in more ancient Greek literature (time period Aeschylus), yet we find it with later Greek authors (eg Euripides). (1912-02-03-GA143, 1912-05-14-GA133)

- Five thousand years ago, human conscience did not exist. When a human soul did something wrong, the furies were perceived in the form of an astral, pictorial apparition, the furies or Erinyes, vengeful beings, appeared to men. (Note: Rudolf Steiner times the appearance of conscience to between sixth and fifth century BC (period between poets: Æschylos and Euripides .. Æschylos who writes about furies and no mention of inner voice of conscience) (1909-10-25-GA116, see Apparitions#1909-10-25-GA116).

- human experience of the moral nature of the universe can be sketched in three stages (1912-02-03-GA143):

- in former times Man had a natural unconscious clairvoyance: and Man had no conscience as we know it today, but were tormented by the furies after committing an unworthy deed

- current times, as clairvoyance faded and disappeared, is a transition phase, when all that the furies formerly performed appears as an inner experience, as conscience.

- in the future, with the emergence of the new conscious clairvoyance, Man will see the karmic compensation of one's deeds. Karmic compensation of deeds will appear to human beings in the form of a living picture, prophetic dream-picture, something which will have to occur in the future because of this deed. This experience will become ever stronger and stronger in the course of time.

- Note: Tomberg also discusses this, see Schema FMC00.591B

- consequence of having or lacking conscience and conscientiousness - see Influence of deceased souls.

- souls who were morally irresponsible in their dispositions in their lives on Earth have to co-operate, for a period after death, in bringing epidemics, illnesses and untimely deaths into the physical sense-world .. due to lack of conscience, they have become servants of the evil spirits of illness and death, and have condemned themselves to this servitude (1913-02-04-GA144)

- certain souls are condemned to serve as servants to the Ahrimanic spirits of death and disease. The cause lies in a lack of conscience in such souls during their earthly life (1913-02-16-GA140)

- entering the Mercury sphere after having spent his life on Earth as a person without a conscience, one condemns himself to become a servant of these evil spirits of illness and death, while he is going through this sphere. (1913-02-17-GA140)

Inspirational quotes

St. Paul (1 Cor. 13:13 [New English Bible])

In a word, there are three things that last for ever: faith, hope, and love; but the greatest of them all is love.

Vaclav Havel (1936-2011)

Hope is not the conviction that something will turn out well. It is the certainty that something is worth doing no matter how it turns out.

Buckminster Fuller

Faith is better than belief. Belief is when someone else does the thinking.

Dostoevsky

You are working for the whole .. acting for the future. Seek no reward, for great is your reward .. the spiritual joy which is only vouchsafed to the righteous Man

In 'The Brothers Karamazov' (1880), one of the key characters, Father Zosima, teaches about living for others, embracing suffering, and finding spiritual joy in righteousness and humility. His teachings reflect a deep belief in moral and spiritual duty without the expectation of material rewards. His teachings include selfless love, spiritual reward (finding peace and joy through inner righteousness, rather than through worldly accomplishments), and responsibility for the whole (the belief that everyone is responsible for the actions of humanity as a whole, and must act accordingly) 1912-11-27-GA069A

The value of the human being is determined by his common sense, his power of judgement and his moral qualities.

Illustrations

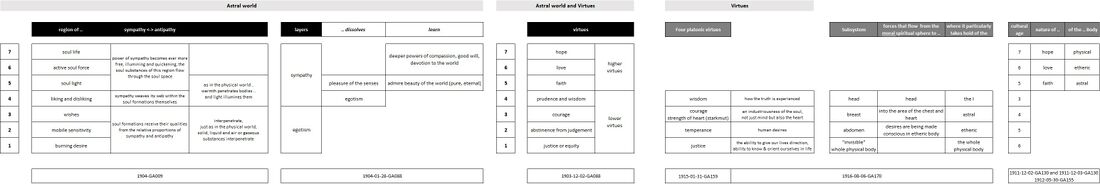

FMC00.261A (double click to enlarge) shows the 'layers' of the Astral world, as mapped to more lower egotistic or higher sympathic, and also to the seven virtues. On the left is a summary of the four platonic virtues and the three highest virtues of Faith Love Hope, with corresponding lecture references.

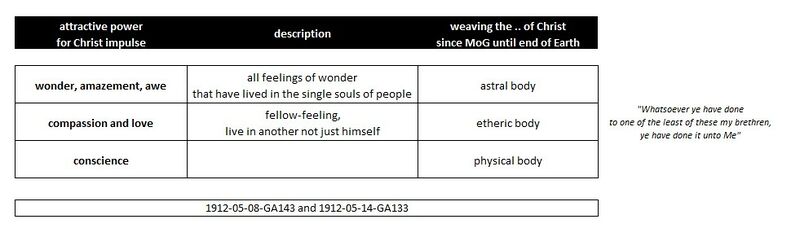

Schema FMC00.371 shows how our state of soul brings us closer to the Christ Impulse.

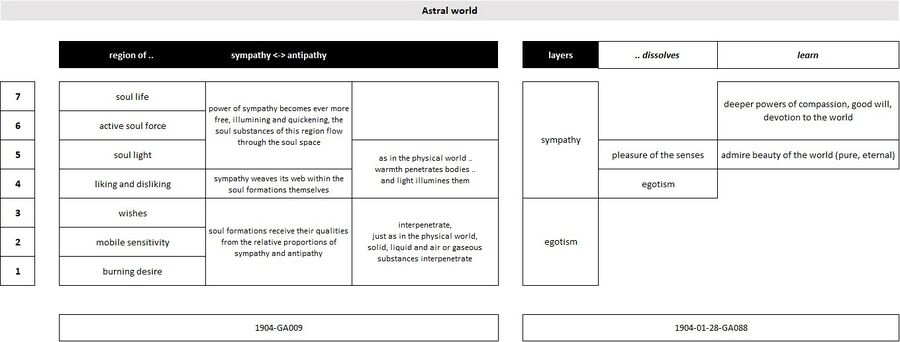

FMC00.261 shows the 'regions' of the astral world.

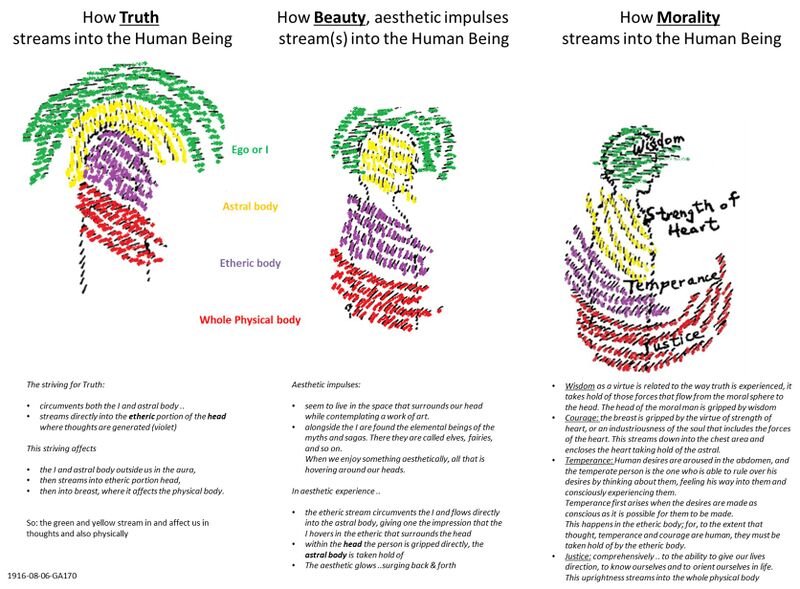

Schema FMC00.262 shows how morality streams into the human being (right)

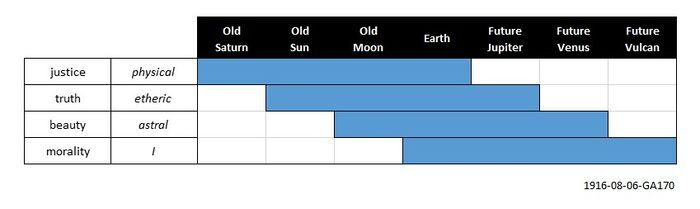

Schema FMC00.066 shows the appearance and disapperance of the bodily principles during the different planetary stages and CoC, and how they serve the development of the main virtues.

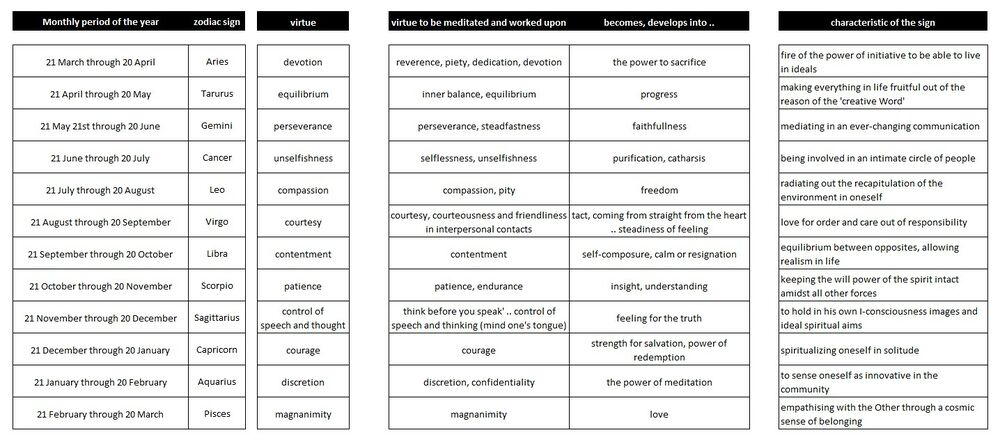

Schema FMC00.522 provides a summary overview table on the twelve monthly meditations on virtues, as provided by Rudolf Steiner. Added on the right is an additional thematic description for the zodiac sign, from Roland van Vliet's lecture on 'The 12 metamorphosed virtues of the zodiac'.

Lecture coverage and references

around 1150 - Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) was a German Benedictine abbess and a writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and as a medical writer and practitioner during the Middle Ages.

As part of her language, Hildegard uses clothing / tapestry / cloud metaphors when describing virtues and the soul (e.g. “clothe,” “garment,” “woven” images), or has the virtues as persons in a drama (eg in 'Ordo Virtutum' (The Play of the Virtues). She sometimes contrasts ordinary materials (wool, flax, tapestry) with being "garbed in the variety of virtues” — virtues framed as a far more precious “garment” and wisdom as a priceless treasure. Her moral teaching is to “desert vice and love virtue”, in other words to cultivate virtues (wisdom, humility, obedience, charity, etc.) as the soul’s real riches.

quote A, from Scivias (Know the Ways of the Lord), Book III, Vision 13, section 15 (approx 1141-1151)

Beware lest you attribute to yourself alone those good qualities which are yours in both your spirit and your works. Rather, attribute them to God, from whom all virtues proceed like sparks from a fire.

quote B, from Letter to Tengswich, Prioress of Andernach; taken from 'The Letters of Hildegard of Bingen, Volume II' (1998)

You have sought wool and flax, and you have woven clothing of tapestry’ as the covering of your spirit. Indeed, each faithful soul puts on clothing of tapestry when it is clothed with the virtue of love, into whose fabric is woven many various images. In clothing such as this, regal Humility, Obedience, Piety, Restraint, Chastity, and Saintliness stand resplendent, along with many thousand qualities like those I have just named. Garbed in this variety of virtues … since you have found the priceless treasure of wisdom, you have truly done as the words of the Gospel teach.

The Chrysopee of the Lord

ancient text attributed to Ramon Lull (or Raymond Lully) (ca. 1232–1315), but this not sure, also no exact date of publication known (until further notice)

see also: Tetractys#The Chrysopee of the Lord

In Man, the Elements capable of starting the work are the Four Cardinal Virtues, namely: Force, Prudence, Temperance and Justice.

The Sage who knew how to develop these Four Virtues in his Soul is assured, by their very presence, of seeing the three Theological Virtues develop in him, namely: Faith, Hope and Charity.

Thus, the continued and attentive practice of the Cardinal Virtues generates and arouses the action of the three superior Virtues.

In their turn, when our three superior Principles are definitively acclimatized in us, they hasten to awaken other presences, those of the Powers of the supreme dyad: Intelligence and Wisdom.

And in turn, these two divine graces awaken another in us: the one that cannot be expressed by words and images.

In the latter is all the Beatitude promised to the elect, through it we participate, creatures, in the Divine Life.

1903-12-02-GA088

There are very specific tasks that the human self has to undertake and carry out during its earthly pilgrimage. Human beings must develop specific virtues that they cannot develop outside this earthly pilgrimage. There are seven such virtues. Human beings came to Earth with the seed of these virtues, and a talent for them; and at the end of their earthly pilgrimage they are to have developed these seven virtues.

If I may make a comparison, I would say: imagine a human being who has a great talent for good will toward his fellow human beings; a wholly generous person, who is, however, entirely poor and therefore not in a position to make use of this gift for beneficence. Similarly, human character has a talent for beneficence in the highest degree; however, human beings cannot yet make any real use of it. Now let us imagine that this person moves to a distant as-yet undeveloped country and attempts to make it productive. Through hard work he produces so much that he then acquires the means to benefit his fellow citizens when he returns to his original country. Now he can carry out what his gift for generosity had prepared him for.

With our first incarnation on Earth we human beings were equipped with a gift for seven such virtues. After millions of years we will have completed our earthly pilgrimage, and these gifts will have been developed into virtues. We will then be able to make use of these abilities in a future planetary evolution. There are four lower virtues:

- Justice or equity

- Abstinence from judgment

- Courage

- Prudence and wisdom

Prudence and wisdom sum it all up; this virtue allows us to pass judgment on our earthly conditions, and in that way to take hold of ourselves in the flow of earthly events. Through the inner work required to achieve these abilities we acquire the power that allows us to engage in the world with leadership and strength.

The three higher virtues are:

- Faith

- Hope

- Love

[Faith]

Goethe expressed it with the words: "Everything transitory is only a parable." If, in everything we see and hear, we see merely a symbol for something eternal, of which it is the expression, then we have faith. That is the first of the three higher virtues.

[Hope]

The second is to develop a feeling for the fact that we should never remain standing at the same place where we are standing now: a feeling for the fact that we human beings today of the fifth post-Atlantean age will later develop ourselves to a higher level. That is hope. We have then faith in the eternal and then trust; hope in higher levels of development.

[Love]

The last virtue is love, the last goal of our cosmos to be developed. For this reason we also call our Earth the cosmos of love. Because we belong to the Earth we are to develop love within ourselves, and when we will have completed our earthly pilgrimage the Earth will be a cosmos of love. Love will then be a power we expect to find in every human being. It will then be present as a matter of course, just as much as the magnetic force of attraction and repulsion is a matter of course in magnets.

Gradually through various incarnations human beings must develop these virtues. We are approximately at the middle point on this path. What these virtues will one day represent has been correctly characterized by Christian theology: "What no eyes have seen, no ear has heard nor the heart of Man conceived. . ." These words signify that no one can imagine the way these virtues will one day exist in their perfected form. From step to step we are creating ourselves through work in the various incarnations we pass through. We descend from the spiritual world equipped for these seven virtues, and then must develop these virtues in life in order to really have them.

Thus our earthly life is nothing more than a journey through a country in order to work there transforming our gifts into true abilities. Those who move into this country must at first devote themselves to this work; and perhaps during the work they will not always be able to see this lofty goal. We develop these virtues by connecting with other people to develop courage, justice, fairness, hope, love, and so forth. We come together with other people, and we must use these encounters in order to develop these virtues. To develop these virtues we must descend out of the spiritual world into the physical world. We become entangled in what the physical world contains; and this world always contains the astral, the world of desires, of longings: kamaloca.

1912-11-27-GA069A

on the virtue of discernment

more on this on: Clairvoyant research of akashic records

It will be necessary above all, so that truth and not error can prevail with the dissemination of spiritual research, that in particular with the confessors of spiritual research critical reason, critical judgement, and common sense and not belief in authority develop. This belief in authority will already wither away if a knowledge spreads among those who like and need spiritual research, a knowledge that is not common, unfortunately, among the confessors of spiritual science that a seer is no higher animal because he can behold in the supersensible world. He does not differ from other human beings, just as little as a chemist, a botanist, a machinist, or a tailor.

The possession of spiritual knowledge does not really determine the value of the human being but only that he can investigate this area and bring the acquired knowledge to his fellow men. Only his common sense determines the value of the human being, his power of judgement and his moral qualities.

Just spiritual research could prove that intellectual and moral qualities of the human being already determine his value, before he enters into the spiritual world, and that if he is inferior there the results of his research will be inferior. It is exceptionally necessary to realise this. Even more than the opponents of spiritual science, its supporters should take stock of themselves in this field.

The four platonic virtues

1912-05-30-GA155

describes how different virtues can be mapped as characteristic of certain cultural ages, as each age has a certain virtue to be developed. The lecture describes the platonic virtues and threefold soul against the cultural ages (with justice for sixth sixth epoch as balance).

Quote A (SWCC)

The second part of the soul is what we usually call the intellectual-soul, or the soul of cultivated feeling. You know that it developed especially in the fourth Postatlantean or Greco-Latin age. The virtue which is the particular emblem for this part of the soul is bravery, valour and courage; we have already dwelt on this many times, and also on the fact that foolhardiness and cowardice are its extremes. Courage, bravery and valour is the mean between foolhardiness and cowardice. The German word gemut expresses in the sound of the word that it is related to this. The word gemut indicates the mid-part of the human soul, the part that is mutvoll, full of mut, Courage, strength and force.

This was the second, the middle virtue of Plato and Aristotle. It is that virtue which in the fourth Postatlantean age still existed in man as a divine gift, while “wisdom” was really only instinctive in the third. Instinctive valour and bravery existed as a gift of the gods (you may gather this from the first lecture) among the people who, in the fourth age, met the expansion of Christianity to the north. They show that among them valour was still a gift of the gods. Among the Chaldean's wisdom, the wise penetration into the secrets of the starry world, existed as a divine gift, as something inspired. Among the people of the fourth Postatlantean age, there existed valour and bravery, especially among the Greeks and Romans, but it existed also among the peoples whose work it became to spread Christianity. This instinctive valour was lost later than instinctive wisdom. Now in the fifth Postatlantean age, as regards valour and bravery, we are in the same position in respect of the Greeks as the Greeks were to the Chaldeans and Egyptians in regard to wisdom. ...

We now consider the virtue of the Consciousness Soul. When we consider the fourth Postatlantean cultural age, we find that "Temperance or Moderation" was still instinctive. Plato and Aristotle called it the chief virtue of the consciousness soul. Again they comprehended it as a state of balance, as the mean of what exists in the consciousness soul. The consciousness soulconsists in man's becoming conscious of the external world through his body. The sense body is primarily the instrument of the consciousness soul, and it is also the sense body through which man arrives at self-consciousness.

...

The ideal of practical wisdom which is to be taken into consideration for the next, the sixth postatlantean age, will be the ideal virtue which Plato calls “justice,” and that is the harmonious accord of these virtues.

Quote B

Compassion, sympathy are those virtues that in the future should bring the most beautiful, most wonderful fruits in human relationships, and for those who correctly understand the impulse of Christ, compassion and love, compassion and sympathy, accordingly, arise, for from this impulse feeling is born. ..

... Through the feat of Calvary, Christ entered earthly development, therefore, every time everything immoral, everything that we do without love, without interest, increases the pain and suffering that are caused to Christ who came to Earth.

The impulse of Christ permeated the whole world, therefore it is to Him that suffering is inflicted.

other translation

Sympathy in grief and joy is the virtue which in the future must produce the most beautiful and glorious fruits in human social life, and, in one who rightly understands the Christ-impulse, this sympathy and this love will originate quite naturally, it will develop into feeling. It is precisely through the anthroposophical understanding of the Christ-impulse that it will become feeling. Through the Mystery of Golgotha, Christ descended into earthly evolution; His impulses, His activities are here now, they are everywhere. Why did He descend to this Earth? In order that through what He has to give to the world, evolution may go forward in the right way. Now that the Christ-impulse is in the world, if through what is immoral, if through lack of interest in our fellow men, we destroy something, then we take away a portion of the world into which the Christ-impulse has flowed.

1915-01-31-GA159

is titled 'The Four Platonic Virtues and Their Relation with the Human Members The Working of Spiritual Forces in the Physical World', and covers the relationship between the virtues and the members of Man's bodily structure

The first virtue which we must consider, if we speak about morality from a comprehensive knowledge of human nature, is the virtue of wisdom. But this wisdom is to be understood in a rather deeper sense, more related to ethics, than is usually done. Wisdom is not something that comes to Man of its own accord; still less can it in the ordinary sense be learned. It is not easy to describe what its meaning for us should be.

- If we pass through life in such a way that events work upon us, and we learn from them how we could have met this or that more adequately, how we could have used our powers more strongly and effectively—if we are attentive towards everything in life, so that when something meets us a second time in a comparable way we can treat it in a way which shows us we have benefited from the first experience

- then we grow in wisdom.

- If we preserve all through life a mood of being able to learn from life, of being able to regard everything brought to us by nature and our experience, in such a way that we learn from it, not simply accumulating knowledge, but growing inwardly better and richer

- then we have gathered wisdom, and what we have experienced has not been worthless for the life of our souls.

1917-03-06-GA175

connects wisdom to head, courage to breast

Through connection with spiritual knowledge, one may conceive a condition in which a man will be conscious of the following: ‘I am living in a state of rhythm, in which I am alternately in the physical world and in the spiritual world. In the physical world I meet with the external physical nature; in the spiritual world I meet with the beings who inhabit that world.’

We shall be able fully to understand this matter if we enter somewhat more deeply into the whole nature of Man, from a particular point of view. You know that it is customary to consider the external science known as biology as a unity, necessarily divided into the head, breast, and lower part with the members attached thereto. In the olden times when man still possessed an atavistic knowledge, he connected other ideas with this division of the human being. The great Greek philosopher, Plato, attributes wisdom to the head, courage to the breast; and the lower emotions of human nature to the lower part of the body.

What pertains to the breast-part of Man can be ennobled when wisdom is added to courage, becoming a wise courage, a wise activity; and that which is considered the lower part of Man, which belongs to the lower parts of his body, if it be rayed through with wisdom, that Plato calls ‘clothed with the sun.’ Thus we see how the soul is divided and attributed to the different parts of the body.

Today, we, who have spiritualscience, which to Plato was not attainable in like manner, speak of these things in much fuller detail.

1917-10-06-GA177

People today, especially if they want to be good people, wanting nothing for themselves but only to be selfless and desire the good of others, will of course seek to develop certain virtues.

These, too, are iron necessities. Now, of course, there is nothing to be said against a desire for virtue, but the problem is that people are not merely desiring to be virtuous. It is quite a good thing to want to be virtuous, but these people want more…

It is much more important to them to be able to feel themselves to be virtuous, to give themselves up entirely to a state of mind where they can say: ‘I am truly selfless, look at all the things I do to improve myself! I am perfect, I am kind, I am someone who does not believe in authority.’ They will then, of course, eagerly follow all kinds of authorities.

To feel really good in the consciousness of having one particular virtue or another is endlessly more important to people today than actually having that virtue. They want to feel they have the virtue rather than practise it.

As a result, certain secrets connected with the virtues remain hidden to them.

They are secrets which people instinctively feel they do not want to know, especially if they are modern idealists who like to feel good in the way I have described….

All kinds of ideals are represented by societies today….

Let us look at the aspect of reality when it comes to people having virtues. Perfection, benevolence, beautiful virtues, rights—it is nice to have them all in the outer social sphere.

However, when people say: ‘It is our programme to achieve perfection in some particular way, benevolence in some particular direction, we aim to establish a specific right', they usually consider this to be something absolute which can be brought to realization as such.

‘Surely’, people will say, ‘it must be a good thing to be more and more perfect?’ And ‘What better ideal can there be but to have a programme that will make us more and more perfect?’

But this is not in accord with the law of reality.

It is right, and good, to be more and more perfect, or at least aim to be so, but when people are actually seeking to be perfect in a particular direction, this search for perfection will after a time change into what in reality is imperfection. A change occurs through which the desire for perfection becomes a weakness. Benevolence will after a time become prejudicial behaviour.

And however good the right may be that you want to bring to realization—it will turn into a wrong in the course of time.

The reality is that there are no absolutes in this world.

You work towards something that is good, and the way of the world will turn it into something bad. We therefore must seek ever new ways, look for new forms over and over again. This is what really matters.

The swing of the pendulum governs all such human efforts. Nothing is more harmful than belief in absolute ideals, for they are at odds with the true course of world evolution.

1923-04-04-GA223

connects the virtues (wisdom, courage, temperance, justice) to the cycle of the year and the festivals

Faith Love Hope

Matthew 17:20

And Jesus said to them, "Because of your unbelief: for verily, I say to you, if you have faith as a grain of mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, 'Move from here to yonder,' and nothing will be impossible for you.

other version

He replied, “Because you have so little faith. Truly I tell you, if you have faith as small as a mustard seed, you can say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move. Nothing will be impossible for you.”

Regarding faith and "blessed who believe without seeing", see also Schema FMC00.397

Rudolf Steiner describes Faith Love Hope in five lectures, see below.

Note the three lectures below without link, also the NOGA, were available in german transcript from steinerdatenbank (no longer available online), they may meanwhile be in the latest GA2025 volumes.

1911-06-14-GA127

title: Faith Love Hope

1911-09-30-GA246

1911-10-07-GA131

And now Soloviev comes to the most complete, the most fully spiritual answer that can be given at the end of the period now closing, before the doors open to that which has so often been intimated to you: the vision of Christ which will have its beginning in the twentieth century. In the light of these facts, a name can be given to the consciousness which Pascal and Soloviev have so memorably described: we can call it Faith. So, too, it has been named by others.

With the concept of Faith we can come from two directions into a strange conflict regarding the human soul. Go through the evolution of the concept of Faith and see what the critics have said about it. Today men are so far advanced that they say Faith must be guided by knowledge, and a Faith not supported by knowledge must be put aside. Faith must be dethroned, as it were, and replaced by knowledge. In the Middle Ages the things of the Higher Worlds were apprehended by Faith, and Faith was held to be justified on its own account.

The fundamental principle of Protestantism, also, is that Faith, alongside knowledge, is to be looked upon as justified. Faith is something which goes forth from the human soul, and alongside of it is the knowledge which ought to be common to all. It is interesting to see how Kant, whom many consider a great philosopher, did not get beyond this concept of Faith. His idea is that what a man should attain concerning such matters as God, immortality and so forth, ought to shine in from quite other regions, but only through a moral faith, not through knowledge.

The highest development of the concept of Faith comes with Soloviev, who stands before the closed door as the most significant thinker of his time, pointing already to the modern world. For Soloviev knows a Faith quite different from all previous concepts of it. Whither has the prevailing concept of Faith led humanity? It has brought humanity to the atheistic, materialistic demand for mere knowledge of the external world, in line with Lutheran and Kantian ideas, or in the sense of the Monistic philosophy of the nineteenth century; to the demand for the knowledge which boasts of knowledge, and considers Faith as something that the human soul had framed for itself out of its necessary weakness up to a certain time in the past. The concept of Faith has finally come to this, because Faith was regarded as merely subjective. In the preceding centuries Faith had been demanded as a necessity. In the nineteenth century Faith is attacked just because it finds itself in opposition to the universally valid knowledge which should stem from the human soul.

And then comes a philosopher who recognises and prizes the concept Faith in order to attain a relationship to Christ that had not previously been possible. He sees this Faith, in so far as it relates to Christ, as an act of necessity, of inner duty.

For with Soloviev the question is not, ‘to believe or not to believe’; Faith is for him a necessity in itself. His view is that we have a duty to believe in Christ, for otherwise we paralyse ourselves and give the lie to our existence. As the crystal form emerges in a mineral substance, so does Faith arise in the human soul as something natural to itself. Hence the soul must say: ‘If I recognise the truth, and not a lie about myself, then in my own soul I must realise Faith. Faith is a duty laid upon me, but I cannot do otherwise than come to it through my own free act.’ And therein Soloviev sees the distinctive mark of the Christ-Deed, that Faith is both a necessity and at the same time a morally free act. It is as though it were said to the soul: You can do nothing else. If you do not wish to extinguish the self within you, you must acquire Faith for yourself; but it must be by your own free act! And, like Pascal, Soloviev brings that which the soul experiences, in order not to feel itself a lie, into connection with the historic Christ Jesus as He entered into human evolution through the events in Palestine. Because of this, Soloviev says: If Christ had not entered into human evolution, so that He has to be thought of as the historic Christ; if He had not brought it about that the soul perceives the inwardly free act as much as the lawful necessity of Faith, the human soul in our post-Christian times would feel itself bound to extinguish itself and to say, not ‘I am’, but ‘I am not’. That, according to this philosopher, would have been the course of evolution in post-Christian times: an inner consciousness would have permeated the human soul with the ‘I am not’. 1 Directly the soul pulls itself together to the point of attributing real existence to itself, it cannot do otherwise than turn back to the historic Christ Jesus.

Here we have, for exoteric thought also, a step forward along the path of Faith in establishing the third way. Through the message of the Gospels, a person not able to look into the spiritual world can come to recognition of Christ. Through that which the consciousness of the seer can impart to him, he can likewise come to a recognition of the Christ. But there was also a third way, the way of self-knowledge, and as the witnesses cited, together with thousands and thousands of other human beings, can testify from their own experience, it leads to a recognition that self-knowledge in post-Christian time is impossible without placing Christ Jesus by the side of man and a corresponding recognition that the soul must either deny itself, or, if it wills to affirm itself, it must at the same time affirm Christ Jesus.

1911-12-02-GA130

title: Faith Love Hope

[Faith]

Does faith, as such, mean anything for mankind? May it not be part of a man's very nature to believe?

Naturally, it might be quite possible that people should want, for some reason, to dispense with faith, to throw it over. But just as a man is allowed for a time to play fast and loose with his health without any obvious harm, it might very well be — and is actually so — that people come to look upon faith merely as a cherished gift to their fathers in the past, which is just as if for a time they were recklessly to abuse their health, thereby using up the forces they once possessed. When a man looks upon faith in that way, however, he is still — where the life-forces of his soul are concerned — living on the old gift of faith handed down to him through tradition. It is not for man to decide whether to lay aside faith or not; faith is a question of life-giving forces in his soul. The important point is not whether we believe or not, but that the forces expressed in the word ‘faith’ are necessary to the soul. For the soul incapable of faith become withered, dried-up as the desert.

There were once men who, without any knowledge of natural science, were much cleverer than those to-day with a scientific world-conception. They did not say what people imagine they would have said: “I believe what I do not know.” They said: “I believe what I know for certain.”

Knowledge is the only foundation of faith. We should know in order to take increasing possession of those forces which are forces of faith in the human soul. In our soul we must have what enables us to look towards a super-sensible world, makes it possible for us to turn all our thoughts and conceptions in that direction.

If we do not possess forces such as are expressed in the word ‘faith’, something in us goes to waste; we wither as do the leaves in autumn. For a while this may not seem to matter — then things begin to go wrong. Were men in reality to lose all faith, they would soon see what it means for evolution. By losing the forces of faith they would be incapacitated for finding their way about in life; their very existence would be undermined by fear, care, and anxiety. To put it briefly, it is through the forces of faith alone that we can receive the life which should well up to invigorate the soul. This is because, imperceptible at first for ordinary consciousness, there lies in the hidden depths of our being something in which our true ego is embedded. This something, which immediately makes itself felt if we fail to bring it fresh life, is the human sheath where the forces of faith are active. We may term it the faith-soul, or — as I prefer — the faith-body. It has hitherto been given the more abstract name of astral body. The most important forces of the astral body are those of faith, so the term astral body and the term faith-body are equally justified.

[Love]

A second force that is also to be found in the hidden depths of a man's being is the force expressed by the word ‘love’. Love is not only something linking men together; it is also needed by them as individuals. When a man is incapable of developing the force of love he, too, becomes dried-up and withered in his inner being. We have merely to picture to ourselves someone who is actually so great an egoist that he is unable to love. Even where the case is less extreme, it is sad to see people who find it difficult to love, who pass through an incarnation without the living warmth that love alone can generate — love for, at any rate, something on earth.

Such persons are a distressing sight, as in their dull, prosaic way, they go through the world. For love is a living force that stimulates something deep in our being, keeping it awake and alive — an even deeper force than faith. And just as we are cradled in a body of faith, which from another aspect can be called the astral body, so are we cradled also in a body of love, or, as in Spiritual Science we called it, the etheric body, the body of life-forces. For the chief forces working in us from the etheric body, out of the depths of our being, are those expressed in a man's capacity for loving at every stage of his existence. If a man could completely empty his being of the force of love — but that indeed is impossible for the greatest egoist, thanks be to God, for even in egoistical striving there is still some element of love. Take this case, for example: whoever is unable to love anything else can often begin, if he is sufficiently avaricious, by loving money, at least substituting for charitable love another love — albeit one arising from egoism. For were there no love at all in a man, the sheath which should be sustained by love-forces would shrivel, and the man, empty of love, would actually perish; he would really meet with physical death.

This shriveling of the forces of love can also be called a shriveling of the forces belonging to the etheric body; for the etheric body is the same as the body of love. Thus at the very centre of a man's being we have his essential kernel, the ego, surrounded by its sheaths; first the body of faith, and then round it the body of love.

[Hope]

If we go further, we come to another set of forces we all need in life, and if we do not, or cannot, have them at all — well, that is very distinctly to be seen in a man's external nature. For the forces we need emphatically as life-giving forces are those of hope, of confidence in the future. As far as the physical world is concerned, people cannot take a single step in life without hope. They certainly make strange excuses, sometimes, if they are unwilling to acknowledge that human beings need to know something of what happens between death and rebirth.

They say:

“Why do we need to know that, when we don't know what will happen to us here from one day to another? So why are we supposed to know what takes place between death and a new birth?”

But do we actually know nothing about the following day?

We may have no knowledge of what is important for the details of our super-sensible life, or, to speak more bluntly, whether or not we shall be physically alive. We do, however, know one thing — that if we are physically alive the next day there will be morning, midday, evening, just as there are to-day. If to-day as a carpenter I have made a table, it will still be there tomorrow; if I am a shoemaker, someone will be able to put on to-morrow what I have made to-day; and if I have sown seeds I know that next year they will come up. We know about the future just as much as we need to know. Life would be impossible in the physical world were not future events to be preceded by hope in this rhythmical way. Would anyone make a table to-day without being sure it would not be destroyed in the night; would anyone sow seeds if he had no idea what would become of them?

It is precisely in physical life that we need hope, for everything is upheld by hope and without it nothing can be done. The forces of hope, therefore, are connected with our last sheath as human beings, with our physical body. What the forces of faith are for our astral body, and the love-forces for the etheric, the forces of hope are for the physical body. Thus a man who is unable to hope, a man always despondent about what he supposes the future may bring, will go through the world with this clearly visible in his physical appearance. Nothing makes for deep wrinkles, those deadening forces in the physical body, sooner than lack of hope.

The inmost kernel of our being may be said to be sheathed

- in our faith-body or astral body,

- in our body of love or etheric body, and

- in our hope-body or physical body; and we comprehend the true significance of our physical body only when we bear in mind that, in reality, it is not sustained by external physical forces of attraction and repulsion — that is a materialistic idea — but has in it what, according to our concepts, we know as forces of hope. Our physical body is built up by hope, not by forces of attraction and repulsion. This very point can show that the new spiritual-scientific revelation gives us the truth.

What then does Spiritual Science give us?

By revealing the all-embracing laws of karma and reincarnation, it gives us something which permeates us with spiritual hope, just as does our awareness on the physical plane that the sun will rise to-morrow and that seeds will eventually grow into plants. It shows, if we understand karma, that our physical body, which will perish into dust when we have gone through the gate of death, can through the forces permeating us with hope be re-built for a new life. Spiritual Science fills men with the strongest forces of hope. Were this Spiritual Science, this new revelation for the present time, to be rejected, men naturally would return to earth in future all the same, for life on earth would not cease on account of people's ignorance of its laws. Human beings would incarnate again; but there would be something very strange about these incarnations. Men would gradually become a race with bodies wrinkled and shriveled all over, earthly bodies which would finally be so crippled that people would be entirely incapacitated. To put it briefly, in future incarnations a condition of dying away, of withering up, would assail mankind if their consciousness, and from there the hidden depths of their being right down into the physical body, were not given fresh life through the power of hope.

This power of hope arises through the certainty of knowledge gained from the laws of karma and reincarnation. Already there is a tendency in human beings to produce withering bodies, which in future would become increasingly rickety even in the very bones. Marrow will be brought to the bones, forces of life to the nerves, by this new revelation, whose value will not reside merely in theories but in its life-giving forces — above all in those of hope.

[Faith Love Hope]

Faith, love, hope, constitute three stages in the essential being of man; they are necessary for health and for life as a whole, for without them we cannot exist. Just as work cannot be done in a dark room until light is obtained, it is equally impossible for a human being to carry on in his fourfold nature if his three sheaths are not permeated, warmed through, and strengthened by faith, love, and hope. For faith, love, hope are the basic forces in our astral body, our etheric body, and our physical body. And from this one instance you can judge how the new revelation makes its entry into the world, permeating the old language with thought-content. Are not these three wonderful words urged upon us in the Gospel revelation, these words of wisdom that ring through the ages — faith, love, hope? But little has been understood of their whole connection with human life, so little that only in certain places has their right sequence been observed.

It is true that faith, love, hope, are sometimes put in this correct order; but the significance of the words is so little appreciated that we often hear faith, hope, love, which is incorrect; for you cannot say astral body, physical body, etheric body, if you would give them their right sequence. That would be putting things higgledy-piggledy, as a child will sometimes do before it understands the thought-content of what is said. It is the same with everything relating to the second revelation. It is permeated throughout with thought; and we have striven to permeate with thought our explanation of the Gospels. For what have they meant for people up to now? They have been something with which to fortify mankind and to fill them with great and powerful perceptions, something to inspire men to enter into the depth of heart and feeling in the Mystery of Golgotha. But now consider the simple fact that people have only just begun to reflect upon the Gospels, and in doing so they have straightway found contradictions upon which Spiritual Science alone can help to throw light. Thus it is only now that they are beginning to let their souls be worked on by the thought-content of what the Gospels give them in language of the super-sensible worlds. In this connection we have pointed out what is so essential and of such consequence for our age: the new appearance of the Christ in an etheric body, for his appearance in a physical body is ruled out by the whole character of our times.

1911-12-03-GA130

has the title: 'Faith, Love, and Hope: towards the sixth cultural age'

quote A

For those who have heard lectures I am giving in various places just now, I would note that these gradual happenings have been described from a different point of view both in Munich and in Stuttgart; the theme, however, is always the same.

What is now being portrayed in connection with the three great human forces, Faith, Love, Hope, was there represented in direct relation to the elements in a man's life of soul; but it is all the same thing. I have done this intentionally, so that anthroposophists may grew accustomed to get the gist of a matter without strict adherence to special words. When we realise that things can be described from many different sides, we shall no longer pin so much faith on words but focus our efforts on the matter itself, knowing that any description amounts only to an approximation of the whole truth. This adherence to the original words is the last thing that can help us to get to the heart of a matter. The one helpful means is to harmonise what has been said in successive epochs, just as we learn about a tree by studying it not from one direction only but from many different aspects.

quote B - longer extract

What then is our present experience?

It is not just of the entering-in of the I; we now experience how one of our sheaths casts a kind of reflection upon the soul.

- The sheath to which yesterday we gave the name of “faith-body” throws its reflection on to the human soul, in this fifth epoch. Thus it is a feature of present-day man that he has something in his soul which is, as it were, a reflection of the nature of faith of the astral body.

- In the sixth post-Atlantean age there will be a reflection within man of the love-nature of the etheric body,

- and in the seventh age , before the great catastrophe, the reflection of the nature of hope of the physical body.

Thus at present it is essentially the force of faith of the astral body which, shining into the soul, is characteristic of our time. Someone might say: “That is rather strange. You are telling us now that the ruling force of the age is faith. We might admit this in the case of those who hold to old beliefs, but to-day so many people are too mature for that, and they look down on such old beliefs as belonging to the childish stage of human evolution.” It may well be that people who say they are monists believe they do not believe, but actually they are more ready to do so than those calling themselves believers. For, though monists are not conscious of it, all that we see in the various forms of monism is belief of the blindest kind, believed by the monists to be knowledge. We cannot describe their doings at all without mentioning belief. And, apart from the belief of those who believe they do not believe, we find that, strictly speaking, an endless amount of what is most important to-day is connected with the reflection the astral body throws into the soul, giving it thereby the character of ardent faith. We have only to call to mind lives of the great men of our age, Richard Wagner's for example, and how even as an artist he was rising all his life to a definite faith; it is fascinating to watch this in the development of his personality. Everywhere we look to-day, the lights and shadows can be interpreted as the reflection of faith in what we may call the ego-soul of man.

1912-01-12-GA246

St-Gallen - Glaube, Liebe, Hoffnung - Nachschrift vorhanden, aber nicht veröffentlicht

-> was only published with GA246 in 2025

1922-01-07-GA210

On the one hand we see knowledge developing, and on the other we see faith.

- We see how knowledge is to contain only what applies to the sense-perceptible world and everything that belongs to it.

- And we see how faith, which must not be allowed to become knowledge, is allotted everything that makes up man's relationship to what is divine and spiritual.

These divergent endeavours express the quest, a quest which cannot achieve an adequate concept and feeling for either the Father God or the Son God without joining forces with the other regions of the earth, with East and West.

How such a global working together in the spirit should take place can be seen especially in the beginnings made by the Russian philosopher Vladimir Soloviev. This Russian philosopher has taken western thought forms into his own thinking. If you are thoroughly familiar with the thought forms of the West, you will find them everywhere in Soloviev's work. But you will find that they are handled differently from the way in which they are handled in the West. If you approach Soloviev with a thinking prepared in the West you will have to relearn something — not about the content of thoughts, but about the attitude of the human being towards the content of thoughts. You will have to undergo a complete inner metamorphosis. Take what I regard as one of the cardinal passages in Soloviev's work, a passage he has invested with a great deal of human striving towards a knowledge of man's being and his relationship with the world. ...

[continued]

More virtues

Reverence and devotion, wonder or amazement

1909-12-22-GA116

on reverence and devotion:

You may remember what I said of the mission of devotion, of the importance of looking up in feeling to some being or some phenomenon which we do not yet understand, but which we revere for the very reason that we have not yet grown up to the level of being able to understand it.

I always like to remind you of how fortunate it is when a Man can say: ‘As a child I heard of a member of our family who was very greatly respected and honoured. I had not yet seen him but I had a profound reverence for him. Then one day the opportunity came, and I was taken to see him. A feeling of profound and holy awe came over me as I laid my hand on the handle of the door of the room where this wonderful person was to be seen.’

In later life a Man will have good reason to be grateful for that feeling of reverent devotion; we owe much gratitude to anyone who aroused a feeling of reverence in us in our early life. That feeling is of great and special value in any life. I have known men who exclaim, when such a feeling of reverent devotion to the spiritual and divine is alluded to: ‘I am an atheist! I cannot revere anything spiritual!’ We can reply: ‘Look at the starry heavens! Could you create those? Look at that wisdom-filled structure and reflect: there it is surely possible to have a feeling of real, true reverence.’ There are many things in the world which our understanding has not yet grown up to, but to which we can look up in reverence. Especially is this the case in youth, when there is so much we can look up to and venerate, without being able to understand it.

A feeling of devotion in early youth is transformed into a very special quality in the second half of life.

We have all heard of persons who just by being themselves, are, as it were, a blessing to those around them. There is no need for them to say anything particular, their presence is enough. It seems as though by the very nature of their being, something invisible flows forth from them to the souls around them. Through their very nature they radiate a healing and beneficent influence on their environment.

To what do these people owe their power of blessing?

They owe it to the circumstance that in their youth they lived a life in which reverence played a part. Reverence in the early part of their life was transformed in later years into a force which works invisibly, pouring forth blessing and help. Here again is a karmic connection which, if we look for it, is clearly and distinctly to be observed. It was really a true feeling for karma which led Goethe to choose as the motto for one of his works, these beautiful words: ‘What we desire in our youth is fulfilled in old age!’ If one only observes the connections to be found within short periods of time, it may certainly seem as though one could speak of unfulfilled wishes, — but taking longer spans of time, this cannot well be said. All these things can pass over into and become part of life's daily round; and as a matter of fact, only one who studies in this anthroposophical way is qualified to educate children, for he will be able to provide them in their early years with that which, as he knows, they will be able to use in the latter part of their life. The responsibility that a man assumes when he instills one thing or another into a child is not realised today. It has become the custom to look down on these things today — to speak of them from the high horse of materialistic thinking. I should like to illustrate this by an experience we ourselves once had here in Berlin.

1912-01-01-GA134

I have, in the course of these lectures, drawn your attention to a perception that Man can acquire when he educates his faculty for knowledge in the way we described; when, that is to say, his soul - in its efforts after knowledge - enters into the moods we characterised as

- wonder, reverence, wisdom-filled harmony with the events of the world, and lastly,

- devotion and surrender to the whole world process.

1912-02-03-GA143

is called 'Conscience and Wonder as Indications of Spiritual Vision in the Past and in the Future'

quote A - about wonder or amazement

If someone is confronted by a fact which he cannot explain with the concepts which he has hitherto acquired, he is thrown into a state of wonder. To give a quite concrete example of this — someone who sees an automobile or a train in motion for the first time in his life will quite certainly be greatly astonished, because within his soul the following thoughts will arise (although soon such things will no longer be anything unusual, even in the interior of Africa). "Judging by all that I have experienced heretofore, it appears quite impossible that something can rush along through the air without anything in front of it by which it is drawn. Nevertheless I see that it rushes along without being drawn! This is truly amazing".

Thus all that Man does not yet know calls forth wonder within him, whereas what he has already seen does so no longer. Only those things which he cannot connect with earlier experiences in life astonish him. Let us keep this truth of everyday life clearly before our minds and compare it with another fact which is also very remarkable. Man is indeed brought in contact with a great many things in daily life which he has never seen before, but which nevertheless he accepts without being amazed. There are innumerable events of this kind. And what sort of events are they?

Now it would indeed be very amazing if, under ordinary conditions, someone who had heretofore been sitting quietly in his chair were to feel himself suddenly beginning to fly up into the air through the chimney! This would certainly be very amazing, and yet if such a thing occurs in a dream, we take part in it without feeling any wonder at all. And we experience even more extraordinary things in dreams at which we are not at all astonished, although they cannot in any way be connected with the occurrences of daily life. In waking-life we are already astonished if someone is able to leap very high into the air, yet in dreams we fly and are not in the least surprised. Thus we are confronted by the fact that, while we are awake, we wonder at things which we have not experienced before, whereas in dreams we do not wonder at all.

...

These two realities — amazement, or wonder, and conscience — are strangely enough eliminated in dreams. Man is accustomed to let such things pass by unnoticed; nevertheless they throw light deep into the foundation of our existence.

In order to clarify these things a little more I should like to point out still another fact which is concerned less with conscience and more with wonder. In ancient Greece the saying arose that all philosophy springs from amazement, from wonder. The experience which lies concealed in this sentence — and it is the experience of the ancient Greeks which is meant — cannot be traced in the most ancient times of Greek development. It is to be found in the history of philosophy only from a certain point of time onward. The reason for this is that in more ancient times men did not yet feel in this way.

But how does it happen that from a certain time onward, just in ancient Greece, men begin to realise that they are amazed?

We have just seen that we are amazed at what does not fit into our life as we have known it hitherto; but if we have only this amazement, the amazement of ordinary life, there is nothing particular in it other than astonishment at the unusual. He who is astonished at the sight of an automobile or a train is not accustomed to see such things, and his astonishment is nothing more than the astonishment at the uncustomary. Far more worthy of wonder, however, than astonishment at motor-cars and railways, at all that is unusual, is the fact that man can also begin to wonder at the usual. Consider for instance how the sun rises every morning. Those who are accustomed to this in their ordinary consciousness are not amazed at it. But when amazement begins to arise over everyday things which we are quite used to see, philosophy and knowledge result. Those who are richest in knowledge are men who can feel wonder over things which the ordinary human being simply accepts, for only then do we become true seekers after knowledge; and it is out of this realisation that the ancient Greeks originated the saying — All philosophy springs from wonder.

...

If now a more developed human being feels the need to explain certain things, to explain occurrences of everyday life, because he is able to wonder even at such simple events, this likewise presupposes that at some earlier time he has seen them quite differently. No one would ever have reached another explanation of the sunrise than that of mere appearances — that it is the sun which rises — if in his soul he did not feel that he had seen it differently in former times. But the sunrise, someone might well object, we have seen occurring in a similar way from our earliest youth; would it not seem to be downright foolishness to fall into amazement because of it?

The only explanation for this is that, if we are nevertheless seized with amazement, we must have experienced it before under entirely other conditions, quite differently from today. For if anthroposophy says that Man existed in a different state between the time of his birth and a previous life, then his amazement at such an everyday occurrence as the accustomed sunrise is nothing other than an indication of this former condition, in which he also perceived the sunrise, but in a different way — without bodily organs. There he perceived it with spiritual eyes and with spiritual ears. And in the moment when, guided by a dim feeling, he says to himself — “You stand before the rising sun, before the foaming sea, before the sprouting plant, and you are filled with wonder!“ ... then in this amazement there lies the knowledge that he once perceived all this in another way than with his physical eyes. It was with his spiritual organs that he saw it before he entered the physical world. He feels dimly that everything appeared differently when he saw it before. And this was and can be due only to himself, to his own experience, before his birth.

Such facts force us to realize that knowledge would be altogether impossible if Man did not enter this earthly life out of a previous super-sensible existence. Otherwise there would be no explanation of wonder and the knowledge resulting from it. Of course Man does not remember in distinct mental images what he experienced differently before birth, but although it does not show itself clearly in thought it lives nevertheless in his feelings. Only through initiation can it be brought down as a clear memory.

But now let us investigate why we do not wonder in dreams. Here we must first answer the question — What then is dream in reality. — Dream is an ancient heritage from former incarnations. Within these earlier incarnations man passed through other states of consciousness of a clairvoyant nature. Later on, during the further course of evolution he lost the capacity to see clairvoyantly into the soul-spiritual world. He had first a shadowy kind of clairvoyance, and his development gradually took its course out of this former shadowy clairvoyance into the clear waking consciousness of our present day, which could evolve in the physical world in order, when fully developed, to ascend once more into the psychic spiritual world with the capacities thus won by his Ego in waking consciousness. But what did Man win in olden days through ancient clairvoyance? Something is still left of it — namely, our dreams. But dreams differ from ancient clairvoyance inasmuch as they are an experience of the man of modern times; who has developed a consciousness which bears within it the impulse for knowledge. Dreams, as the remnant of a former state of consciousness, do not contain the desire for knowledge, and this is why man experiences the difference between waking consciousness and dream-consciousness.

Wonder, which was not to be found in the shadowy clairvoyance of ancient times, can also not enter the dream-consciousness of today. Amazement, wonder, cannot reach into our dreams, but we experience them in waking consciousness when we turn our attention towards the outer world. In his dreams man is not in this outer world, for they transport him into the spiritual realm, and there he no longer experiences the things of the physical plane. Yet it is just with regard to this physical world that he has learned to wonder. In dreams he accepts everything as he accepted it in ancient clairvoyance, when he could simply take things as they were, because spiritual forms came to him and showed him the good or evil which he had done. For this reason he did not then need wonder. Thus dreams show us through their own nature that they are a heritage from ancient times, when there was neither wonder at the things of everyday life, nor conscience.

Here we reach the point where we must ask — "If man was once already clairvoyant, why then could he not remain so? Why did he descend? Did the gods drive him out without reason?" Now it is a fact that man would never have attained what lies in wonder and in conscience, had he not descended. In order that he might win for himself knowledge and conscience man descended; for he can only win them if he is separated for a time from the spiritual world. And here below he has attained them, attained knowledge and conscience, in order that he may ascend with them once more.

...

Amazement and desire for knowledge on the one hand, and conscience on the other, are living witnesses of the spiritual world. They cannot be explained without taking the spiritual worlds into account. One who can experience awe at the phenomena of the world, who can feel reverence and wonder for these phenomena, will be more easily inclined to become an Anthroposophist than many others. It is the more developed souls who are able to wonder ever more and more. For the less wonder a soul is able to experience, the less developed it is.

Now it is true that man approaches all his daily experiences — the everyday occurrences of life — with much less wonder than he feels, for instance, when admiring the starry heavens in all their splendour. But the higher development of the soul, in the true sense, begins only when we can wonder at the smallest flower, the tiniest petal, the most insignificant beetle or worm, just as much as at the greatest events in the cosmos. If we go to the root of these things, they are indeed very strange. As a rule man is easily inclined to demand an explanation for things which effect him in a sensational way. Those who live in the vicinity of a volcano, for instance, will seek an explanation for the causes of volcanic eruptions, because they must pay particular heed to these things, and therefore devote more attention to them than to everyday proceedings. Indeed people who live far away from volcanoes also attempt to find an explanation concerning them, because they find such occurrences startling and sensational. But when a man enters life with a soul so constituted that he is amazed at all things, because he divines something spiritual in everything about him, he will then be no more amazed at a volcano than perhaps at the little bubbles and tiny craters which he observes in his cup of milk or coffee at the breakfast-table. He is just as much interested in small things as in the greatness of a volcanic eruption.

To be able to approach everything with wonder is a reminiscence of our perception before birth.

...

Just as certain people living at the present time have become thoughtful natures because they won certain powers in former incarnations which now reveal themselves as wonder, as a kind of memory of these earlier lives, just so they will take certain powers with them into their next incarnation if they now acquire a knowledge of the spiritual worlds. Those, however, who refuse to accept an explanation of the law of reincarnation at the present time, will fare very badly in the future world. For such souls these facts will be a terrible reality.

1924-04-27-GA236

It is not this kind of causal connection only that the study of karma can disclose to us. Many other things, too, become intelligible, which to external observation seem at first obscure and incomprehensible. But if we are to participate in the great change in thinking and perception that is essential in the near future if civilisation is to progress and not fall into decline, it is incumbent upon us to develop, in the first place, a sense for what in ordinary circumstances is beyond our grasp and the understanding of which requires insight into the deeper relationships of existence.

A Man who finds everything comprehensible may, of course, see no need to know anything of more deeply lying causes. But to find everything in the world comprehensible is a sign of illusion and merely indicates superficiality. In point of fact the vast majority of things in the world are incomprehensible to the ordinary consciousness.

To be able to stand in wonder before so much that is incomprehensible in everyday life — that is really the beginning of a true striving for knowledge.

A call that has so often gone out from this platform is that anthroposophists shall have enthusiasm in their seeking, enthusiasm for what is implicit in anthroposophy. And this enthusiasm must take its start from a realisation of the wonders confronting us in everyday life. Only then shall we be led to reach out to the causes, to the deeper forces underlying existence around us.

This attitude of wonder towards the surrounding world can spring both from contemplation of history and from observation of what is immediately present. How often our attention is arrested by events in history which seem to indicate that human life here and there has lost all rhyme and reason. And human life does indeed lose meaning if we focus our attention upon a single event in history and omit to ask: How do certain types of character emerge from this event? What form will they take in a later incarnation? ... If such questions remain unasked, certain events in history seem to be entirely meaningless, irrelevant, pointless. They lose meaning if they cannot become impulses of soul in a subsequent life on earth, find their balance and then work on into the future.

Empathy, compassion

1904-12-15-GA053

On empathy, see also Stephen Covey's 'First seek to understand, before to be understood'.

Furthermore, it is necessary that man rid himself of something that is difficult to cast aside in our civilization, namely, the urge to learn 'what is new'. This has tremendous influence on the soul-organ. If one cannot get hold of a newspaper fast enough and tell the news to somebody else, if a person also cannot keep what he has seen and heard to himself and cannot suppress the desire to pass it on, his soul will never achieve any degree of development.

It is also necessary that one acquire a certain definite manner of judging one's fellowmen. It is difficult to attain an uncritical attitude, but understanding must take the place of criticism. It suppresses the advancement of the soul if you confront your fellowman immediately with your own opinion. We must hear the other out first, and this listening is an extraordinarily effective means for the development of the soul eyes. Anybody who reaches a higher level in this direction owes it to having learned to abstain from criticizing and judging everybody and everything. How can we look understandingly into somebody's being? We should not condemn but understand the criminal's personality, understand the criminal and the saint equally well.

Empathy for each and everyone is required and this is what is meant with higher, occult 'listening'. Thus, if a person brings himself with strict self-control to the point of not evaluating his fellowman, or the rest of the world for that matter, according to his personal judgment, opinion and prejudice and instead lets both work on him in silence, he has the chance to gain occult powers. Every moment during which a person becomes determined to refrain from thinking an evil thought about his fellowman is a moment gained.

A wise man can learn from a child. A simple-minded person can consider a wise man's utterances in like manner as a child's babblings, convinced that he is superior to a child and unaware of the practicality of wisdom. Only when he has learned to listen to the stammering of a babe as if it were a revelation, has he created within him power that wells forth from his soul.

1910-11-12-GAXXX

is a lecture titled 'morality and karma', and goes into envy and falsehood vs compassion

No GA known (yet), for info on publication of this lecture, see here

.. it may be said, first of all, that envy and falsehood are visibly an offence against a fundamental element of social life: they are an offence against the feeling of compassion.

Compassion does not only imply sharing another's grief and pain, but it also implies experiencing his value.

Compassion is a quality which is not greatly developed among men. It still contains a great amount of egoism. Of Herder it is said, for instance (he intended to study medicine) that he fainted when he first entered an operating theatre where a corpse was to be dissected; he fainted not through compassion, but through weakness and egoism, because he could not bear that sight.

Compassion must become less selfish; we should be able to rejoice at another person's success and rise; we should be able to look upon his good qualities without any feeling of bitterness.

Compassion is a fundamental element in the soul life which we share with others because all human soul experiences are connected with each other.

Envy and falsehood in particular offend against the capacity of appraising another person's value. We damage our fellow man through envy and falsehood.

Envy and falsehood bring us in opposition to the course of the universe; by envy and falsehood we harm the laws which govern the world's course of events. They can easily be recognized as errors and people do not tolerate them.

1921-12-02-GA079

also on the undeveloped natural empathy